Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 27 I&N Dec. 449 (BIA 2018): Defining Aggravated Felony Obstruction of Justice

- Introduction: Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 27 I&N Dec. 449 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 449-50

- Ninth Circuit (and other Circuits) Remand: 27 I&N Dec. at 851

- Interpretive Method and Discussing the Ninth Circuit Decision: 27 I&N Dec. at 451-53

- Interference in an Investigation or Proceeding: 27 I&N at 453-56

- Accessory After the Fact Included: 27 I&N Dec. at 457-60

- New Rule: 27 I&N Dec. at 460-61

- Application of Definition to Conviction in the Instant Case: 27 I&N Dec. at 461

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 27 I&N Dec. 449 (BIA 2018)

On September 11, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) published a precedential decision in the Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 27 I&N Dec. 449 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. The Board considered the definition of an aggravated felony “offense relating to obstruction of justice” under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The Board held that section 101(a)(43)(S) “encompasses offenses covered by chapter 73 of the Federal criminal code, [18 U.S.C. 1501-1521] (2012), or any other Federal or State offense that involves (1) an affirmative and intentional attempt (2) that is motivated by a specific intent (3) to interfere either in an investigation or proceeding that is ongoing, pending, or reasonably foreseeable by the defendant, or in another's punishment resulting from a completed proceeding.” In accordance with its holding, the Board held that a conviction for accessory to a felony under section 32 of the California Penal Code is an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) provided that the conviction results in a term of imprisonment of at least one year.

This is the second published decision that the Board has issued in this case. In 2012, the Board reached the same result with regard to the respondent in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 25 I&N Dec. 838 (BIA 2012) [PDF version]. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit granted the respondent's petition for review on the basis that aspects of the Board's section 101(a)(43)(S) definition were impermissibly vague. The new Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo clarifies the 2012 decision in response to the Ninth Circuit remand.

In this article, we will review the factual and procedural history of the new Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision, the Board's analysis and conclusions, and what the decision will mean in section 101(a)(43)(S) cases going forward. To read about other important immigration precedent decisions, please see our article index [see index].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 449-50

The respondent, a native and citizen of Mexico, was admitted to the United States as a lawful permanent resident on May 23, 2002.

On December 28, 2007, the respondent was convicted of the crime of accessory to a felony in violation of section 32 of the California Penal Code. He was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 16 months for this conviction.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent on the basis of his conviction. He was charged as being removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the INA for having been convicted of an aggravated felony. The DHS alleged that his conviction in violation of section 32 of the California Penal Code was an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the INA.

The respondent contested the charges against him in removal proceedings. He argued that his conviction did not fall under section 101(a)(43)(S) because it did not relate to an ongoing judicial proceeding. The respondent sought termination of removal proceedings on that basis. The Immigration Judge, however, sided with the DHS, concluding that the definition of an offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) is not limited to obstruction offenses involving an ongoing judicial proceeding. Accordingly, the Immigration Judge denied the respondent's motion to terminate proceedings and ordered him removed to Mexico.

The Board initially dismissed the respondent's appeal in an unpublished decision. However, on May 17, 2011, the Ninth Circuit published a decision in a separate case titled Trung Thanh Hoang v. Holder, 641 F.3d 1157 (9th Cir. 2011) [PDF version], in which the Ninth Circuit, relying upon the Board's prior precedent decisions interpreting section 101(a)(43)(S), held that a crime is an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice only when “it interferes with an ongoing proceeding or investigation.” Id. at 1164.

The Board sua sponte (on its own motion) reopened the instant proceedings. in light of the Ninth Circuit decision in Hoang because section 32 of the California Penal Code requires that the violator have acted with the intent to aid a principal in avoiding arrest, trial, conviction, or punishment, and is not strictly limited to obstruction in an ongoing proceeding or investigation. On June 27, 2012, the Board published its first decision in the instant proceeding, Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 25 I&N Dec. 838 (BIA 2012). In that decision, the Board clarified its prior precedent decisions on section 101(a)(43)(S) and held that, while an offense relating to obstruction of justice must have as an element “the affirmative and intentional attempt, with specific intent, to interfere with the process of justice,” “the existence of [an ongoing criminal investigation or trial] is not an essential element of 'an offense relating to obstruction of justice.'” Id. at 841. Under this more expansive definition than that adopted by the Ninth Circuit in Hoang, the Board again concluded that the respondent had been convicted of an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S).

Ninth Circuit (and other Circuits) Remand: 27 I&N Dec. at 851

The respondent filed a petition for review of the 2012 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision with the Ninth Circuit. In 2016, The Ninth Circuit granted the petition for review in a published decision titled Valenzuela Gallardo v. Lynch, 818 F.3d 808 (9th Cir. 2016) [PDF version], holding that the Board's 2012 definition of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” was impermissibly “vague.” Specifically, the Ninth Circuit wrote that the Board's definition was vague because it did not “not give[] an indication of what it does include in 'the process of justice,' or where that process begins and ends.” Id. at 819. It concluded that the phrase “process of justice” was “amorphous.” Id. at 822. It wrote that, “[a]bsent some indication of the contours of 'process of justice,' an unpredictable variety of specific intent crimes could fall within it, leaving us unable to determine what crimes make a criminal defendant deportable under [section] 101(a)(43)(S) and what crimes do not.” Id. at 820.

In accord with its conclusion, the Ninth Circuit remanded the case to the Board. It gave the Board two options on remand:

1. “For consideration of a new construction [of section 101(a)(43)(S)]”; or

2. For application of the Board's previous construction of section 101(a)(43)(S) from Matter of Espinoza, 22 I&N Dec. 889 (BIA 1999) [PDF version], which informed the Ninth Circuit's decision in Hoang.

As we will see, the Board opted for the first path in its new Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision. While ultimately reaching the same result, the Board clarified its 2012 construction of section 101(a)(43)(S) by addressing the concerns expressed by the Ninth Circuit in its 2016 decision in Valenzuela Gallardo v. Lynch. We will discuss the Board's analysis and conclusions in the forthcoming sections.

Before continuing, it is worth noting that the Ninth Circuit was not the only circuit to decline to follow the Board's 2012 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision. The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit agreed with the Ninth Circuit in its own published decision, Victoria-Faustino v. Sessions, 865 F.3d 869, 876 (7th Cir. 2017) [PDF version], and applied the Matter of Espionoza definition instead. Furthermore, in an unpublished decision in Cruz v. Sessions, 689 F. App'x 328, 329 (5th Cir. 2017) (per curiam), the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit vacated a BIA decision following the Board's 2012 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision because it had been vacated by the Ninth Circuit. The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit declined to follow Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo on different grounds, in Flores v. Att'y Gen. U.S., 856 F.3d 280, 287 n.23 (3d Cir. 2017) [PDF version], suggesting that the statute was unambiguous and the Board's conclusion otherwise was incorrect.

It remains to be seen whether the Seventh and Ninth Circuits will defer to the new Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision. To learn about the jurisdictions of these circuits, and those of the Third and Fifth Circuits as well, please see our full article on the subject [see article].

Interpretive Method and Discussing the Ninth Circuit Decision: 27 I&N Dec. at 451-53

The Board was tasked on remand with determining the proper construction of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” under section 101(a)(43)(S). Although section 101(a)(43)(S) also covers offenses related to perjury or subordination of perjury and bribery of a witness, the Board's inquiry was restricted solely to obstruction of justice.

The Board explained that in order to determine whether the respondent's conviction was for “an offense relating to obstruction of justice,” it would “apply the categorical approach by focusing on whether the elements of the California State statute of conviction proscribed conduct that categorically falls within the Federal generic definition of an offense relating to obstruction of justice.” In short, the question was whether a conviction in violation of section 32 of the California Penal Code is necessarily an offense relating to obstruction of justice, in which case it would be an aggravated felony. The Board cited to the decision of the Supreme Court on the categorical approach in Mathis v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2243, 2248 (2016), which we discuss in a full article on site [see article].

In light of the Ninth Circuit remand [see section], the Board opted to “respectfully take the opportunity to clarify our prior precedents regarding the contors of the generic definition of an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the [INA].” In doing so, the Board invoked two important Supreme Court decisions on administrative deference. First, it invoked Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 866 (1984) [PDF version], which sets forth a two-step inquiry for courts to undertake when determining whether they owe deference to an administrative agency's interpretation of a statute. Under Chevron, courts owe deference where (1) the statute is ambiguous, and (2) the agency's interpretation is reasonable (note: the Board is an administrative agency). Second, the Board invoked Nat'l Cable & Telecomms. Ass'n v. Brand X Internet Servs., 545 U.S. 967 (2005) [PDF version], which effectively extended Chevron to cases where the court had interpreted an ambiguous statute in one way and the administrative agency subsequently interpreted it in a different way. The Board thus signaled its intention to formulate a construction of section 101(a)(43)(S) which would be owed deference by the courts.

Accordingly, the Ninth Circuit recognized that the language of section 101(a)(43)(S) was ambiguous. The Board explained that the Ninth Circuit had reasoned that the statute “does not clearly answer whether an offense relating to obstruction of justice must involve interference in an ongoing investigation or proceeding.” The Ninth Circuit had then declined to follow the Board's prior construction by invoking the doctrine of constitutional avoidance, which we discuss in some detail in our article on Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S.Ct. 830, 842 (2018) [see article], and which was also cited to by the Board in the instant case. In Negusie v. Holder, 555 U.S. 511, 523 (2009) [PDF version], the Supreme Court wrote that, where an immigration statute was ambiguous, the Board had the responsibility “to fill the statutory gap in a reasonable fashion.” It is worth noting that if the Third Circuit follows its line of reasoning in Flores v. Att'y Gen. U.S., see above, in which it suggested that the statute was unambiguous and that the Board's conclusion otherwise was incorrect, that court would likely not defer to the Board's new interpretation of section 101(a)(43)(S).

The Board explained that because the INA does not define the phrase “obstruction of justice,” it “f[ound] it appropriate to adopt a generic definition 'based on the 'generic, contemporary meaning' of [that phrase] at the time the statute was enacted,” citing to Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 27 I&N Dec. 256, 260-61 (BIA 2018) [see article]. In order to craft a generic definition, the Board “survey[ed] Federal and State law, Federal sentencing guidelines, the Model Penal Code, and scholarly commentary to determine the common meaning of the phrase 'obstruction of justice' in 1996, when section 101(a)(43)(S) was enacted.” However, in a footnote, the Board noted that state law is of limited use in this specific inquiry. The Board cited to Esquivel-Quintana v. Sessions, 137 S.Ct. 1562, 1570-72 (2017), wherein the Supreme Court employed a similar method in analyzing the phrase “sexual abuse of a minor” in section 101(a)(43)(A) of the INA [see article].

Interference in an Investigation or Proceeding: 27 I&N at 453-56

In both the 2012 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision and in Matter of Espinoza, the Board had used the language of chapter 73 of the Federal criminal code (18 U.S.C. 1501-1520 (2006)) for guidance on the scope of “obstruction of justice” under section 101(a)(43)(S). Chapter 73 of the Federal criminal code lists criminal offenses under the heading of “Obstruction of Justice.”

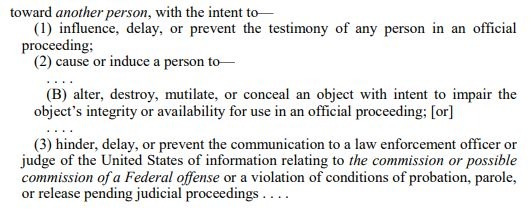

The Board explained that many of the specific criminal provisions in chapter 73 do require “interference in an ongoing investigation or proceeding.” In Matter of Espionza, 22 I&N Dec. at 892, the Board wrote: “The intent of the two broadest provisions, [18 U.S.C. 1503] (prohibiting persons from influencing or injuring an officer or juror generally) and [18 U.S.C. 1510] (prohibiting obstruction of criminal investigations), is to protect individuals assisting in a federal investigation or judicial proceeding and to prevent a miscarriage of justice in any case pending in a federal court.” Conversely, however, many specific crimes detailed in chapter 73 are not limited to interference in ongoing investigations or proceedings. The Board listed 18 U.S.C. 1512 and 1519 as examples of such provisions. Significantly, the Board showed that, prior to the enactment of section 101(a)(43)(S), chapter 73 (18 U.S.C. 1512(b) (1994)) had simply proscribed the knowing use of intimidation, physical force, threats, corrupt persuasion, or misleading conduct

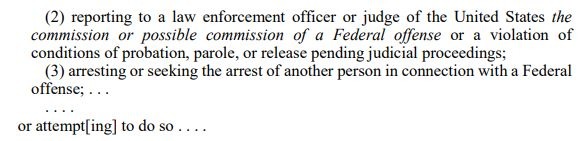

Similarly, 18 U.S.C. 1512(c) (1994) had proscribed intentionally harassing another person and thus hindering, delaying, preventing, or dissuading him or her from

The Board explained the significance of the two above provisions: “For purposes of these crimes, 'an official proceeding need not be pending or about to be instituted at the time of th[e] offense.” Citing to several precedent court decisions on the issue, the Board found that “prior to the enactment of section 101(a)(43)(S), it was well settled that interference in an ongoing or pending proceeding was not a necessarily element of the crimes listed in [8 U.S.C.] 1512-rather, the Government needed only to establish that an individual acted with the intent to frustrate an investigation or proceeding that he or she believed might be instituted.”

Subsequent to the enactment of section 101(a)(43)(S), the Board noted that the position of courts on 8 U.S.C. 1512 has remained consistent. In fact, the Supreme Court of the United States has twice held or synthesized prior decisions — first in Arthur Andersen LLP v. United States, 544 U.S. 696, 707-09 (2005) [PDF version]; and second in Marinello v. United States, 138 S.Ct. 1101, 1110 (2018) [PDF version] — that the prospect that proceedings were reasonably foreseeable by the defendant when he or she committed the offenses in question was sufficent for purpose of 8 U.S.C. 1512. The Board also found support for this reading of 18 U.S.C. 1512 in its legislative history.

The Board addressed 18 U.S.C. 1503 — one of the provisions discussed in Matter of Espionza which requires the obstruction to have been related to an ongoing judicial proceeding — in a footnote. The Supreme Court twice held — in Marinello, 138 S.Ct. at 1104; and United States v. Aguilar, 515 U.S. 593, 598-99 (1995) [PDF version] — that the statute requires proof of interference in ongoing proceedings. However, the Board found these provisions distinguishable from the broader section 101(a)(43)(S). Specifically, the Board held that the Court's decisions “were based on the fact that the object of the word 'obstruct' in [sections 1503 and 7212(a)] was 'the due administration of' justice or a particular title of the United States Code, respectively.” However, “the object of 'obstruction' in section 101(a)(43)(S) is simply the word 'justice,' suggesting that Congress intended section 101(a)(43)(S) of the [INA] to apply more broadly than the provisions at issue in Aguilar and Marinello.”

For these reasons, the Board “conclude[d] that Congress did not intend interference in an ongoing or pending investigation or proceeding to be a necessary element of an 'offense relating to obstruction of justice' under the [INA].” Instead, the Board held that Congress intended “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” under section 101(a)(43)(S) to cover crimes involving:

(1) an affirmative and intentional attempt

(2) that is motivated by a specific intent

(3) to interfere with an investigation or proceeding that is ongoing, pending, or 'reasonably foreseeable by the defendant.'

The Board noted that were it to adopt the alternative position, “a conviction for either witness tampering under [18 U.S.C. 1512] or obstruction of a Federal investigation under [18 U.S.C. 1519] would never be a predicate for removal under section 101(a)(43)(S).” This is because, in applying the categorical approach, if a statute is missing an element of the generic offense, “a person convicted under that statute is never convicted of the generic crime.” Descamps v. United States, 570 U.S. 254, 276 (2013) [see article]. The Board found that it was “highly unlikely” that Congress intended for section 101(a)(43)(S) to sweep so narrowly.

Accessory After the Fact Included: 27 I&N Dec. at 457-60

The Board stated that it agreed with the Ninth Circuit “that there must be limits on what ['obstruction of justice' under section 101(a)(43)(S)] covers.” To this effect, the Board found that, while Chapter 73 “provides important guidance,” it was “not reasonable to conclude that Congress intended chapter 73 to be [the] sole reference under Federal law.” The Board took the position that 18 U.S.C. 3 (1994), which proscribes “accessory after the fact” under federal criminal law, “is also important for discerning the commonly understood meaning of the phrase 'obstruction of justice' in the [INA].”

18 U.S.C. 3 — which has remained unchanged since it was enacted in 1948 — states that “Whoever, knowing that an offense against the United States has been committed, receives, relieves, comforts or assists the offender in order to hinder or prevent his apprehension, trial or punishment, is an accessory after the fact.” The Ninth Circuit has issued several instructive precedent decisions on 18 U.S.C. 3. In United States v. Lopez, 482 F.3d 1067, 1076 (9th Cir. 2007) [PDF version], the Ninth Circuit held that the statute requires that the violator act with the “specific intent to frustrate law enforcement.” In United States v. Hobson, 519 F.2d 765, 769 (9th Cir. 1975) [PDF version], the Ninth Circuit held that individuals who had assisted a convict following his escape from prison were guilty of accessory after the fact. The Board explained that “[a]n individual may be convicted of accessory under the fact … if he acts with specific intent to interfere in an ongoing, pending, or reasonably foreseeable investigation or proceeding” or if he or she “knowingly assist[s] an individual convicted of a crime with the specific intent to interfere in his punishment resulting from a completed proceeding.”

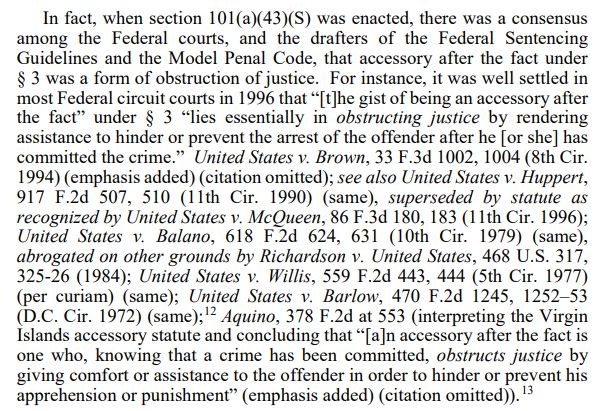

In Matter of Batista-Hernandez, 21 I&N Dec. 955, 962 (BIA 1997) [PDF version], the Board found that an alien who had been convicted of being an accessory after the fact had been convicted of an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S). In reaching that conclusion, the Board had relied on the published decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in United States v. Barlow, 470 F.2d 1245, 1252-53 (D.C. Cir. 1972) [PDF version], which considered accessory after the fact to be a form of obstruction of justice. In the instant decision, the Board wrote that, “[f]or more than half a century, the crime of accessory after the fact under Federal and State law has been regarded as a form of obstruction of justice.” The Board cited to a list of Federal court decisions, as well as the Model Penal Code and the drafters of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, to support this conclusion:

The Board wrote that given the extensive judicial history as well as the Federal Sentencing Guidelines' position that accessory after the fact was a form of obstruction of justice, “it is highly unlikely that Congress intended to exclude the crime of accessory after the fact under [18 U.S.C. 3] from the phrase 'obstruction of justice' in section 101(a)(43)(S) when it enacted that provision.” Therefore, the Board concluded that it would be “unreasonably restrictive” to limit its inquiry to chapter 73, notwithstanding the fact that chapter 73 is titled “Obstruction of Justice.” It noted that in Trainmen v. Baltimore & O. R. Co., 331 U.S. 519, 528 (1947) [PDF version], the Supreme Court held — in the Board's paraphrasing — that “while a heading within a statute may be instructive, it does not conclusively settle the statute's meaning.” Furthermore, in its recent Matter of Alvarado, 26 I&N Dec. 895, 897 (BIA 2016) [see article], the Board held that 18 U.S.C. 1621 (2012), which is titled “Perjury generally,” did not provide the sole reference point for understanding the meaning of the term “perjury” in 1996 under section 101(a)(43)(S).

In support of its reliance on 18 U.S.C. 3, the Board added that Congress could have limited the scope of “obstruction of justice” to chapter 73 if it had intended to do so. Aggravated felonies found in sections 101(a)(43)(B)-(F) and (H)-(P) contain similar restrictions (e.g., see aggravated felony crime of violence at section 101(a)(43)(F), which incorporates 18 U.S.C. 16 for its definition). The Board noted that in Keene Corp. v. United States, 508 U.S. 200, 208 (1993) [PDF version], the Supreme Court held that “where Congress includes particular language in one section of a statute but omits it in another …, it is generally presumed that Congress acts intentionally and purposely in the disparate inclusion or exclusion.” Furthermore, in Esquivel-Quintana, 137 S.Ct. at 1571, the Court did not rely solely upon 18 U.S.C. 2243 (2012) for its definition of “sexual abuse of a minor” under section 101(a)(43)(A), because the aggravated felony provision “does not cross-reference [18 U.S.C. 2243(a)], whereas many other aggravated felonies in the [INA] are defiend by cross reference to other provisions of the United States Code.”

New Rule: 27 I&N Dec. at 460-61

The Board restated its “clarified” construction of section 101(a)(43)(S): It consists of offenses covered by chapter 73 of the Federal criminal code or any other Federal or State offense that involves “(1) an affirmative an intentional attempt (2) that is motivated by a specific intent (3) to interfere either in an investigation or proceeding that is ongoing, pending, or reasonably foreseeable by the defendant, or in another's punishment resulting from a completed proceeding.”

The Board held that its clarified definition is consistent with its prior holdings in Matter of Espionza and Matter of Batista-Hernandez. It reaffirmed its conclusion from Matter of Espionza, 22 I&N Dec. at 894, that section 101(a)(43)(S) does not include within its scope “every offense that, by its nature, would tend to obstruct justice,” but rather only those offenses that fall under its new construction. It also reaffirmed its holding that misprision of a felony under 18 U.S.C. 4 (2012) would not constitute obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) because that statute does not reference the purpose with which the concealment of a felony was undertaken. Id. Conversely, in a footnote, the Board wrote that convictions in violation of 18 U.S.C. 401(3) (contempt of court) and 18 U.S.C. 3146 (failure to appear) would both constitute aggravated felony obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) because they “require that one act with the specific intent to interfere in an ongoing proceeding.”

The Board cited to both Chevron and Brand X in clarifying its definition, suggesting that its view is that its new construction of section 101(a)(43)(S) is entitled to deference from the judiciary.

Application of Definition to Conviction in the Instant Case: 27 I&N Dec. at 461

The Board found that “the respondent's offense of accessory to a felony under section 32 of the California Penal Code is clearly an offense relating to obstruction of justice” under its clarified definition. The Board analogized section 32 of the California Penal Code to 8 U.S.C. 3, in that it “requires a violator to aid the principal, with knowledge that the principal has committed a crime, and with the specific intent to interfere in the principal's arrest, trial, conviction, or punishment.” The California Supreme Court outlined these elements in People v. Nuckles, 298 P.3d 867, 870 (Cal 2013) [PDF version]. As we discussed, the Board held in Matter of Batista-Hernandez that accessory after the fact under Federal law is aggravated felony obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S).

Because the respondent did not dispute that he was convicted of a crime for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year, the Board “conclude[d] that his conviction is categorically one for an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice that renders him removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the [INA].” Thus, the Board dismissed the respondent's appeal.

Conclusion

The Board's new decision in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo clarifies its definition of “obstruction of justice” under section 101(a)(43)(S). While the Board's reading of the statute is broad, it is not unlimited, leaving certain offenses that relate generally to obstruction outside of its scope. It remains to be seen whether the Seventh and Ninth Circuits will defer to the Board's new construction of section 101(a)(43)(S) and whether the Third will reassess its prior position on the statute. We will continue to update the website with more information on the issue as it becomes available.

An alien facing criminal charges should always consult with an experienced immigration attorney for guidance on the possible immigration ramifications of different case dispositions. In the event that the alien has a criminal conviction or is facing removal due to a conviction, he or she should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately for case-specific guidance.

To learn more about related issues, please see our website's full section on criminal aliens [see category].