- Introduction: Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 27 I&N Dec. 256 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 256-57

- Pertinent Statutes: 26 I&N Dec. at 72

- Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 258-61

- Dissenting Opinion: 27 I&N Dec. at 261-64 (Malphrus, dissenting)

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 27 I&N Dec. 256 (BIA 2018)

On April 20, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published decision in the Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 27 I&N Dec. 256 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. In the decision, the Board concluded that the offense of stalking in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code is not “a crime of stalking” under the deportability provision found in section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). In so doing, the Board overturned its prior precedent decision in the case, Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 26 I&N Dec. 71 (BIA 2012) [PDF version]. In the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision, the Board had held that the offense of stalking in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code was “a crime of stalking” under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i). However, it is important to note that, while the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez ruling was then overturned by the board in 2018 decision to the extent that it had held that section 646.9 of the California Penal Code was a “crime of stalking” under the INA, the Board retained its definition of a generic stalking offense from the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision. The Board reached this conclusion in the instant case because it found that the statute allowed for a conviction if the stalking caused the victim to fear nonphysical injury to him or herself or his or her family, whereas the generic Federal offense requires that the victim is caused to fear bodily injury or death him him or herself or his or family.

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of the Matter of Sanchez-Lopez litigation, the Board’s analysis and reasoning for overturning its 2012 precedent, and what the new precedent decision means going forward. In addition, we will address a dissenting opinion authored by Board Member Garry Malphrus, who was also part of the 3-member panel that issued the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision.

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 256-57

The respondent, a native and citizen of Peru, was admitted to the United States for lawful permanent residency in 1993.

On April 19, 2011, the respondent was convicted of stalking in violation of section 646.9(b) of the California Penal Code. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent based on this conviction, charging him as removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA. The DHS also charged the respondent as removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) as an alien who was convicted of an aggravated felony under the INA.

On March 31, 2012, the Immigration Judge found that the respondent was removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) and denied the respondent’s applications for relief. The Immigration Judge did not sustain the charge that the respondent had been convicted of an aggravated felony. The respondent appealed to the BIA from the Immigration Judge’s decision finding him removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i).

On November 29, 2012, the Board dismissed the respondent’s appeal in a precedential decision titled Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 26 I&N Dec. 71 (BIA 2012). The Board specifically held that the crime of stalking in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code is “a crime of stalking” as defined in the INA at section 237(a)(2)(E)(i).

The respondent appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. On January 28, 2014, the Ninth Circuit granted a motion by the Government to remand the record to the BIA for reconsideration of its holding in the first Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision. The Board reaffirmed its decision on March 23, 2015, and, in so doing, once again dismissed the respondent’s appeal. On appeal from the reaffirmation, the Ninth Circuit again granted an unopposed motion by the Government to remand the record to the BIA to consider whether the respondent was removable.

On this second remand before the Board, the respondent argued that his conviction for stalking in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code is not for “a crime of stalking” as defined in section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA. The DHS, in a supplemental brief, argued that the respondent’s conviction in violation of section 646.9 was a predicate for removal under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA.

For the foregoing reasons, the Board would accept the respondent’s arguments and overrule its 2012 decision in Matter of Sanchez-Lopez.

Pertinent Statutes: 26 I&N Dec. at 72

The question in the instant case is whether a conviction in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code is “a crime of stalking” in violation of section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA. Accordingly, before proceeding, we must understand these two statutes.

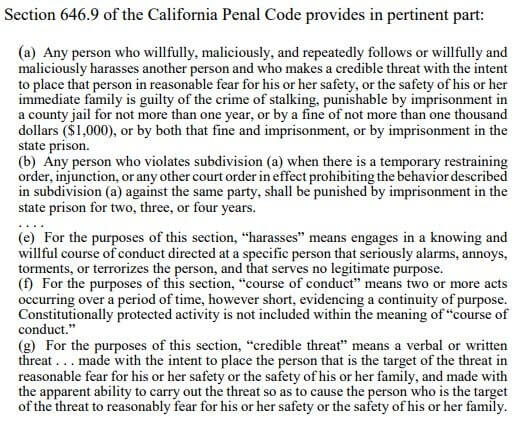

First, the Board excerpted the pertinent part of section 646.9 in Matter of Sanchez-Lopez, 26 I&N Dec. 71, 72 (BIA 2012):

Section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) reads as follows:

“Any alien who at any time after admission is convicted of a crime of domestic violence, a crime of stalking, or a crime of child abuse, child neglect, or child abandonment is deportable.” (Emphasis added.)

Please see the relevant discussion of this provision in our main article on section 237(a)(2) for analysis of the entire statute and links to relevant articles on the statute [see section].

Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 258-61

In this section, we will examine why the Board ultimately overruled its 2012 decision in Matter of Sanchez-Lopez and held in the instant 2018 reconsideration of Matter of Sanchez-Lopez that a conviction in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code is not “a crime of stalking” under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA.

In its 2012 decision, the Board held that “a crime of stalking” in violation of section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) contains the following elements: “(1) conduct that was engaged in on more than a single occasion, (2) which was directed at a specific individual, (3) with the intent to cause that individual or a member of his or her immediate family to be placed in fear of bodily injury or death.” The Board applied this generic definition to section 646.9 of the California Penal Code and determined that the California statute fell under its umbrella.

As we noted before, the Government had sought remand on appeal before the Ninth Circuit. By doing so, the Government wanted the Board to reconsider its decision in order to assess whether there was a “realistic probability” that the California statute would be applied to conduct falling outside of the Board’s definition of a generic “crime of stalking,” as outlined in the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision. Specifically, the Government asked the Board to consider whether there was a realistic probability that section 646.9 would be applied “to conduct committed with the intent ‘to cause and [which] causes a victim to fear for ‘safety’ in the non-physical sense.” The Government cited to Gonzales v. Duenas-Alvarez, 549 U.S. 183 (2007) [PDF version], and United States v. Grisel, 488 F.3d 844 (9th Cir. 2007) (en banc) [PDF version] in requesting remand.

In Duenas-Alvarez, the Supreme Court set forth the standard for determining that a state statute creates a crime that is not covered by a Federal immigration statute, that is, that there must be “a realistic probability, not a theoretical possibility, that the State would apply its statute to conduct that falls outside the generic definition.”

In Chavez-Solis v. Lynch, 803 F.3d 1004, 1009 (9th Cir. 2015) [PDF version], the Ninth Circuit set forth the two ways in which it can be established that there is a “realistic probability” that a State statute would be applied to conduct outside the scope of a generic Federal crime. First, citing to Duenas-Alvarez, 549 U.S. at 193, the Ninth Circuit explained that in meeting this burden the alien can cite to examples, either his or her own cases or other cases, where the State statute was applied to conduct outside the scope of the pertinent immigration provision. Alternatively, the respondent may appeal to the language of the State statute itself to establish that it “explicitly defines a crime more broadly than its generic definition…” In the latter event, no “legal imagination” would be required to determine that there is a realistic probability that the State statute would be applied to conduct outside the scope of the pertinent immigration provision. For this reason, the Ninth Circuit explained, if the language of the State statute itself is broader than the Federal generic crime, the respondent would not need to cite to any specific examples of the statute being applied to conduct not covered by the relevant INA provision.

In its initial motion to remand, the Government took the position that both California courts and the Ninth Circuit have, in prior cases, “declined to consider the victim’s ‘fear for his or her safety or the safety of his or her family’ under section 646.9 as being limited to death or fear of bodily injury.” Thus, the Government argued that, based on existing case-law, there was a “realistic probability,” notwithstanding the statutory language, that section 646.9 of the California Penal Code would be applied to conduct outside the scope of generic stalking set forth in the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision. However, the Board rejected this argument, concluding that its “survey of California cases shows that the conduct prosecuted under section 646.9 invariably involves statements and patterns of conduct that reasonably imply an intent to cause the victim to either personally fear physical harm or fear such harm to his or her family.” In addition, the Board in 2012 also held that all of the California cases cited to by the Government in support of its motion “involved situations where the totality of the circumstances surrounding the defendant’s conduct implied a threat against the physical safety of the victim or his or her family.”

However, the Board in 2018 recognized that, under Chavez-Solis, citing to previous applications of a statute is only one of two ways to establish that there is a realistic probability that a State criminal statute will be applied to conduct outside the scope of a generic Federal crime. For this reason, the Board explained that its conclusion in 2012 that the Government had not cited to any cases where section 646.9 of the California Penal Code had been applied to cover conduct outside the scope of generic stalking was not, by itself, dispositive. Accordingly, the Board moved to assess the statutory language of section 646.9 in order to ascertain whether the language of the statute was “overly inclusive” with respect to the definition of generic stalking set forth in the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision. Chavez-Solis, 803 F.3d at 1010.

The Board explained that “[i]n 1994, the California Legislature amended section 646.9 ‘to require that the target of the threat need only fear for the target’s safety or that of his or her family while deleting any requirement that the threat be ‘against the life of, or [threaten] great bodily injury to’ the target.’” To this effect, the Board cited to People v. Zavala, 30 Cal. Rptr. 3d 398, 404 (App. Ct. 2005) [PDF version]. Here, the Board found significance in the fact that California “explicitly replaced the specific reference to death or great bodily injury with the term ‘safety’…” Specifically, the Board reasoned from this that “stalking offenses committed with the intention of causing a victim to fear nonphysical injury, either personally or to his or her family, may be prosecuted in California.” Accordingly, the Board concluded “that the statutory text of section 646.9 establishes that there is a ‘realistic probability’ that California would apply the statute to conduct falling outside the definition of the ‘crime of stalking’ … outlined in Matter of Sanchez-Lopez.”

Having concluded that section 646.9 is categorically overbroad with respect to “a crime of stalking” in section 237(a)(2)(E)(i), the Board next assessed whether the California statute was “divisible,” that is, whether it set forth alternative elements (i.e., facts that must be established to sustain a conviction). If so, the Board would be able to resort to the record of conviction for the purpose of determining the specific part of the statute under which the respondent was convicted. However, the Board concluded that the term “safety” in section 646.9 was indivisible, thus precluding the Board from looking any further into the conduct of the respondent that led to his conviction. To learn more about divisibility in the criminal aliens conduct, please see our collection of articles on important precedents in this area [see index].

The Board explained that the DHS “appear[ed] to concede” that section 646.9 is overbroad with respect to its definition of “a crime of stalking” in the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision. However, the DHS also argued that the Board should expand its definition of a “crime of stalking” based on its commonly understood meaning (based on the common elements of State and Federal stalking statutes) either in 2012 or in 2017. Here, the Board acknowledged that the common elements of State and Federal stalking statutes have “evolved” since section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) was added to the INA in 1996. However, the Board cited to its decision in Matter of Cardiel, 25 I&N Dec. 12, 17 (BIA 2009) [PDF version], in explaining that it was required by the Supreme Court in Taylor v. United States, 495 U.S. 575, 598 (1990) [PDF version], to define offenses “based on the ‘generic, contemporary meaning’ of the statutory words at the time the statute was enacted.” The DHS countered that in Voisine v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2272, 2281 (2016) [PDF version] [see article], the Supreme Court had allowed for an assessment of the common law in analyzing the statutory language. However, the Board explained that, even in Voisine, the Court had examined the legislative history and “state-law backdrop” that existed at the time of the enactment of the statute in question.

For the foregoing reasons, the Board concluded that a conviction in violation of section 646.9 of the California Penal Code is not “a crime of stalking” under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA, and the Board overruled its decision in Matter of Sanchez-Lopez and vacated all prior orders in the instant proceedings “to the extent they hold contrary.” Notably, the Board did not thereby reverse the portion of Matter of Sanchez-Lopez where it defined a generic stalking offense as defined in section 237(a)(2)(E)(i). Having sustained the respondent’s appeal, the Board concluded that the respondent was not removable and terminated removal proceedings.

Dissenting Opinion: 27 I&N Dec. at 261-64 (Malphrus, dissenting)

Board Member Garry Malphrus authored a dissenting opinion in Matter of Sanchez-Lopez. Although his opinion is not controlling, it is worth examining for its insights into the issues at play in the case, the possibility that future Board panels may be persuaded to adopt its reasoning, and its predictions for the effect of the opinion of the Board in the case going forward.

Malphrus agreed with the majority on several key points. First, he agreed that the Board must assess the California statute with respect to the generic definition of stalking in effect when Congress enacted section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA in 1996. For that reason, Malphrus, like the majority, rejected the DHS’s argument that the Board could update its definition of generic stalking to account for subsequent developments in State and Federal stalking statutes. Like the majority, he noted that the Board has consistently rejected such an approach, including in a recent decision he authored, Matter of Alvarado, 26 I&N Dec. 895, 897 (BIA 2016) [PDF version] [see article].

However, Malphrus differed from the majority regarding the definition of “a crime of stalking.” He would have expanded the definition of “stalking” to encompass section 646.9 of the California Penal Code based on a survey of the State and Federal stalking statutes in effect when section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA was enacted.

Malphrus explained that in 1996, there was a range of conduct covered by different State stalking statutes. He agreed with the majority that the Board’s definition of generic “stalking” must have specific parameters, and he stated that his definition would have excluded some stalking statutes in effect in 1996. However, regarding the Board’s definition from the 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision, Malphrus wrote that “the key point for our purposes is that the generic definition that we provided … which was based on a fear of bodily injury or death, is not substantially different from a fear for one’s safety, which some of the States, including California, have incorporated in their definition of stalking.” He noted that in 1996, several States other than California included a reasonable fear for one’s safety in their stalking statutes. Noting s the similarity between “a fear of bodily injury or death” and a “reasonable fear for one’s safety” and the fact that numerous State stalking statutes in effect in 1996 included the latter, Malphrus took the position that the Board “could and should amend that definition to include a reasonable fear for one’s safety or that of a family member and thus find that section 646.9 is a categorical match to the generic definition of stalking.”

Malphrus agreed with the majority that, under Ninth Circuit precedent, the Board could not conclude that there was not a “realistic probability” that section 646.9 of the California Penal Code would not be applied to conduct that did not implicate “a fear of bodily injury or death” based on the language of the California statute. However, the fact that the Board failed to find any examples of the statute being applied to conduct that did not implicate “a fear of bodily injury or death” in fact “strongly indicates that the reasonable fear for one’s safety is not substantially different from a reasonable fear of bodily injury or death…”

Although Malphrus had concluded that the Board was precluded from expanding its definition of generic “stalking” based on subsequent developments in the law after 1996, he noted that the majority’s unnecessarily narrow definition of generic stalking will mean that “a very small number of States will be covered going forward” However, he recognized that even if the Board had adopted his preferred definition encompassing fear for one’s safety, “many stalking statutes may not be covered…” He attributed these results to the Supreme Court’s requirement that the Board adhere to the categorical approach, which we discuss in a series of articles [see index]. To this effect, Malphrus reiterated several concerns that he has involving the current Supreme Court jurisprudence requiring the strict categorical approach. We discuss another instance where Malphrus addressed these concerns in a concurring opinion he authored in Matter of Chairez, 27 I&N Dec. 21, 25-26 (BIA 2017) (Malphrus, concurring) [PDF version] [see article].

In an additional interesting point, Malphrus noted that the generic definition of “a crime of stalking” arrived at by the Board in 2012 was based on the 1993 Model Penal Code definition of the offense rather than based on a survey of State statutes in effect in 1996. If the DHS ultimately pursues the issue further, this point may be an issue before Federal appellate courts.

He concluded by taking the position that it was highly unlikely that Congress had intended for California and states with similarly constructed stalking statutes to not be covered by section 237(a)(2)(E)(i).

Conclusion

Despite overturning the outcome in its 2012 Matter of Sanchez-Lopez decision, the Board left in place its definition of generic stalking under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the INA. In effect, the Board clarified the scope of its definition, finding that it excludes stalking statutes that require less than the victim having “a fear of bodily injury or death.” Although the case specifically involves section 646.9 of the California Penal Code, its effect may be far-reaching. Notably, Board Member Malphrus suggested in his dissenting opinion that the Board’s definition of generic stalking will have the effect of excluding most State stalking statutes from the scope of section 237(a)(2)(E)(i).

Whether an alien is removable or subject to any other provisions of the INA due to a criminal conviction will always require a case-specific analysis. An alien who has a criminal conviction or is facing removal should always consult with an experienced immigration attorney for counsel and representation. Whether an alien facing charges under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) will be affected by the instant decision will depend on the specific statute involved.