Overview of INA 101(a)(43)(C) - Aggravated Felony for Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, Explosives, or Destructive Devices

- Introduction

- Overview of Section 101(a)(43)(C) — Illicit Trafficking in Firearms or Destructive Devices or in Explosive Materials (Including Discussion of Deportability Provision in section 237(a)(2)(C))

- Understanding Meaning of Term “Illicit Trafficking”

- Criminal Statutes Incorporated Into Section 101(a)(43)(C)

- Relevant Case-Law

- Soto-Hernandez v. Holder, 729 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2013)

- Oppedisano v. Holder, 769 F.3d 146 (2d Cir. 2014)

- Kuhali v. Reno, 266 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2001)

- Joseph v. Attorney General of U.S., 465 F.3d 123 (3d Cir. 2006)

- United States v. Guillen-Cruz, 853 F.3d 768 (5th Cir. 2017)

- Franco-Casasola v. Holder, 773 F.3d 33 (5th Cir. 2014)

- United States v. Ochoa, 861 F.3d 1010 (9th Cir. 2017)

- Moncrieffe v. Holder, 569 U.S. 184 (2013)

- Conclusion

Introduction

In this article, we will examine the aggravated felony provision, found in section 101(a)(43)(C) of the INA, of illicit trafficking in firearms, destructive devices, or explosive materials. In so doing, we will examine the language of section 101(a)(43)(C) itself, the language of other relevant statutes, and important administrative and judicial precedents on the subject.

This article is part of our series of articles on firearms offenses and immigration law. To learn more about the subject, please see our related articles on section 101(a)(43)(E) [see article] and our index on firearms and immigration law [see index].

Please see the relevant sections of our site to learn more about the intersection between criminal and immigration law [see category] and removal and deportation defense [see category].

Overview of Section 101(a)(43)(C) — Illicit Trafficking in Firearms or Destructive Devices or in Explosive Materials (Including Discussion of Deportability Provision in section 237(a)(2)(C))

Section 101(a)(43)(C) defines as an “aggravated felony” the “illicit trafficking in firearms or destructive devices (as defined in [18 U.S.C. 921]) or in explosive materials (as defined in [18 U.S.C. 841(c)]).

Rather than list the types of firearms, destructive devices, and explosive devices covered, the INA instead incorporates two statutes from the federal criminal laws: 18 U.S.C. 921 and 18 U.S.C. 841(c). It is worth noting here that the deportability provision at section 237(a)(2)(C), which covers any alien who after being admitted is convicted of certain firearms offenses, also incorporates section 18 U.S.C. 921(a). You may read about section 237(a)(2)(C) in our full article on the criminal deportability grounds [see article]. Although we will focus on section 101(a)(43)(C) here, it is worth noting that the definitions we discuss from 18 U.S.C. 921(a) are also pertinent to section 237(a)(2)(C).

As we will find, the incorporated criminal statutes are definitional in nature, meaning that they define terms which are used in specific crimes but do not themselves define any crimes. An easy way to think about the relationship between section 101(a)(43)(C) and the cited to criminal statutes is that:

Illicit trafficking in firearms, destructive devices, or explosive materials is an aggravated felony under INA 101(a)(43)(C)

“Firearms” and “destructive devices” are defined in 18 U.S.C. 921

“Explosive materials” are defined in 18 U.S.C. 841(c)

The same principle applies to subsection 237(a)(2)(C). This deportability provision covers several offenses relating to firearms and destructive devices, and those firearms and destructive devices are defined in 18 U.S.C. 921(a).

Thus, two criteria must be satisfied in order for an offense to be an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C). It must (1) involve illicit trafficking (2) in firearms, destructive devices, or explosive materials, as those terms are defined in either 18 U.S.C. 921 or 18 U.S.C. 841(c).

Below, we will examine section 101(a)(43)(C) in three main sections. First, we will examine the meaning of the term “illicit trafficking.” Second, we will examine the definitions of “firearms, explosives, and destructive devices” as used in section 101(a)(43)(C). Third and finally, we will study relevant case-law on section 101(a)(43)(C).

Before continuing, it is important to note that section 101(a)(43)(U) of the INA describes as an aggravated felony an attempt or conspiracy to commit any aggravated felony. Thus, an attempt or conspiracy to illicitly traffic firearms, explosives, or destructive devices may lead to aggravated felony charges under section 101(a)(43)(U).

Understanding Meaning of Term “Illicit Trafficking”

The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) has never explicitly defined the term “trafficking” with regard to firearms, destructive devices, or explosive materials under section 101(a)(43)(C). See Soto-Hernandez v. Holder, 729 F.3d 1, 2 (1st Cir. 2013) [PDF version]. However, the Board defined the same term in the context of section 101(a)(43)(B), which defines as an aggravated felony “illicit trafficking in a controlled substance” (emphasis added) in Matter of Davis, 20 I&N Dec. 536 (BIA 1992) [PDF version].

In Matter of Davis, 20 I&N Dec. at 241, the Board cited to Black's Law Dictionary, 1340 (5th ed. 1979) to explain that “trafficking” is defined as “Trading or dealing in certain goods and commonly used in connection with narcotics sales.” It added that “[e]ssential to the term in this sense is its business or merchant nature, the trading or dealing of goods, although only a minimal degree of involvement may be sufficient under the precedents of the Board to characterize an activity as 'trafficking' or a participant as a 'trafficker.'” Id. (Emphasis added.) In turn, the Board explained that the term “illicit” in section 101(a)(43)(C) “simply refers to the illegality of the trafficking activity.” Id.

The Matter of Davis' definition of “illicit trafficking” has generally been extended by immigration judges and the Board to section 101(a)(43)(C). In Matter of Flores, 26 I&N Dec. 155, 157 n.2 (BIA 2013) [PDF version], the Board wrote that “the 'trafficking' and 'illicit trafficking' concepts have applications beyond section 101(a)(43)(B) of the [INA]. E.g., section 101(a)(43)(C) of the [INA]…” This footnote is noteworthy because the Board expressly followed Matter of Davis, albeit in a section 101(a)(43)(B) determination.

Several circuits have recognized that the Board has in fact extended its definitions from Matter of Davis to adjudications in the section 101(a)(43)(C) context, albeit in unpublished decisions. In Soto-Hernandez, at 2, the United States Court of Appeals wrote of the Board that “[o]n [the basis of Matter of Davis], the BIA held that [the Petitioner's] delivery of a firearm to a purchaser fit the definition of trafficking…” In Kuhali v. Reno, 266 F.3d 93, 107 (7th Cir. 2001) [PDF version], the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit wrote that “[i]n its decision, the Board construed the term 'trafficking' as used [in INA 101(a)(43)(C)] in light of its decision in [Matter of Davis]…”

In both Soto-Hernandez and Khali, courts upheld the BIA's application of Matter of Davis to section 101(a)(43)(C). In Soto-Hernandez, at 2, the First Circuit held that “we cannot hold that the BIA's interpretation of commerce as focusing primarily on some element of financial exchange is impermissible.” In Khali, at 108, the Seventh Circuit wrote: “Because the INA does not define the term 'trafficking' in [section 101(a)(43)(C)], and the Board construed the term to hinge on the business or merchant nature of the alien's firearms conviction, as exemplified by his acts of trading or dealing, we must ask under Chevron whether the Board's construction is a reasonable one. We think it is.”

Thus, in order for an offense to constitute “illicit trafficking” for purpose of section 101(a)(43)(C) — under current interpretation — the offense must involve an illegal transaction of a “business or merchant nature.” An alien may be found to have committed a section 101(a)(43)(C) offense even in he or she was only involved “to a minimal degree.”

Criminal Statutes Incorporated Into Section 101(a)(43)(C)

The text of section 101(a)(43)(C) itself does not define “firearms, destructive devices, or explosive materials.” Instead, as we explained, it incorporates definitional statutes from the federal criminal laws. Below, we will example each of these statutes.

18 U.S.C. 921 [PDF version] provides the definitions for “firearms” and “destructive devices.” We will examine key points from the statute in brief, but interested readers may consult the full statute (see previous PDF) for all of its provisions.

Under 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(3), the term “firearm” means:

A. any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive;

B. the frame or receiver of any such weapon;

C. any firearm muffler or firearm silencer; or

D. any destructive device.

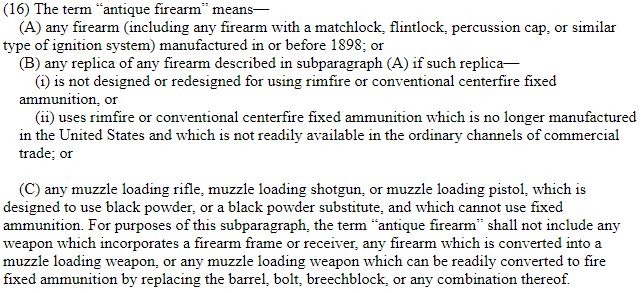

It is important to note that the term “firearm” does not include an antique firearm. Under 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(16), the term 'antique firearm” encompasses certain types of firearms manufactured in or before 1898 and certain replicas of those firearms. You may read the full definition below:

18 U.S.C. 921(a)(4) defines the term “destructive device” as meaning:

A. any explosive, incendiary, or poison gas-(i) bomb, (ii) grenade, (iiii) rocket having a propellant charge of more than four ounces, (iv) missile having an explosive or incendiary charge of more than one-quarter ounce, (v) mine, or (vi) device similar to any of the devices in [18 U.S.C. 921(a)(4)(A)];

B. any type of weapon (other than a shotgun or a shotgun shell which the Attorney General finds is generally recognized as particularly suitable for sporting purposes) by whatever name known which will, or which may be readily converted to, expel a projectile by the action of an explosive or other propellant, and which has any barrel with a bore of more than one-half inch in diameter; and

C. any combination of parts either designed or intended for use in converting any device into any destructive device described in [A or B] and from which a destructive device may be readily assembled.

The definition of “destructive device” expressly excludes from its scope “any device which is neither designed nor redesigned for use as a weapon; any device, although originally designed for use as a weapon, which is redesigned for use as a signaling, pyrotechnic, line throwing, safety, or similar device; surplus ordnance sold, loaned, or given by the Secretary of the Army pursuant to the provisions of section 4684(2), 4685, or 4686 of title 10; or any other device which the Attorney General finds is not likely to be used as a weapon, is an antique, or is a rifle which the owner intends to use solely for sporting, recreational or cultural purposes.”

We must turn to 18 U.S.C. 841(c) [PDF version] for the definition of “explosive materials.” The statute defines the term as meaning “explosives, blasting agents, and detonators.”

Relevant Case-Law

Having examined the definitions of “firearms,” “destructive devices,” and “explosive materials,” we will now look at key section 101(a)(43)(C) cases in addition to those cases that we discussed above. In this section, we will be looking exclusively at Federal circuit court decisions. To learn about the jurisdictions of each of the Federal circuit courts, please see our full article on the subject [see article].

Soto-Hernandez v. Holder, 729 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2013) [PDF version]

The First Circuit explained that the alien had been “convicted of unlawfully delivering a .45 caliber semi-automatic pistol to a purchaser 'without complying with' the Rhode Island General Laws. Id. at 2. Specifically, Soto had violated the state prohibition on the delivery of a pistol or revolver less than seven days following an application or purchase, see R.I.G.L. 11-47-35, as well as the requirement that pistols be delivered unloaded, securely wrapped, and with the bill of sale enclosed, see R.I.G.L. 11-47-26.” Id. at 2-3.

The immigration judge determined that the petitioner's conviction was an aggravated felony trafficking in firearms offense under section 101(a)(43)(C). Id. at 3. The petitioner argued that his conviction was not an aggravated felony because it did not “rise to the level of being in the business or a merchant in the trading or dealing of firearms.” Id. The First Circuit, however, held that the “BIA's definition of 'trafficking in firearms' … as encompassing any commercial exchange … is reasonable and consistent with the statute.” Id. at 5. The First Circuit did not reach the merits of the question of whether trafficking in a single firearm is covered in section 101(a)(43)(C) due to the petitioner's failure to raise the argument in administrative proceedings, but it concluded that, if the petitioner had done so , it would have rejected the claim that trafficking in a single firearm is not covered by the statute. Id. Finally, it held that section 101(a)(43)(C) is not ambiguous and that it does cover one-time sales. Id. at 5-6.

Oppedisano v. Holder, 769 F.3d 146 (2d Cir. 2014) [PDF version]

The aggravated felony provision in Oppendisano was actually section 101(a)(43)(E)(ii) [see article], not section 101(a)(43)(C). However, the Second Circuit addressed section 101(a)(43)(C) in brief in response to one of the petitioner's arguments. The BIA had found that the petitioner had been convicted of an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(E)(ii) due to his conviction for unlawful possession of ammunition. Id. at 149. One of the petitioner's arguments against this conclusion was that Congress did not mention ammunition in several other provisions of the INA dealing with firearms offenses, including sections 101(a)(43)(C) and 237(a)(2)(C). Id. at 152. However, the Second Circuit was not convinced that Congress intended these sections to be “coextensive with [section 101(a)(43)(E)(ii)].” Id. Instead, the differing language of the provisions “suggests that these subsections cover different swaths of criminal activity.” Id.

Kuhali v. Reno, 266 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2001) [PDF version]

The alien was convicted of unlicensed export of firearms under 22 U.S.C. 2778(b)(2). Id. at 98. The immigration judge held, and the BIA affirmed, that this conviction was for an aggravated felony. Id. The Court explained that the criminal provision prohibits exporting firearms in the absence of a valid export license. Id. The Second Circuit listed that a conviction under 2778(b)(2) “entails proof of four elements: the (1) willful (2) export or attempted export (3) of articles listed on the United States Munitions List (4) without a license.” (Internal citations omitted.) Id. at 104.

The petitioner made two arguments in favor of his claim that his conviction was not for an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C). First, he argued that his conviction was “essentially a licensing offense,” and therefore was not a firearms offense as defined in section 101(a)(43)(C). Id. at 108. However, the Second Circuit held that this point was immaterial under the Board's reasonable reading of section 101(a)(43)(C), explaining that “[a]ll that must be decided is whether the offense has a business or merchant nature…” Id. The petitioner's second argument was that the act of exporting is not of a business or merchant nature, thus leaving the conviction outside of the Board's reading of section 101(a)(43)(C). Id. Specifically, he noted that the statute only requires proof of export, not of a commercial transaction. Id. However, the Second Circuit concluded that 22 U.S.C. 2778 “reflects Congress' judgment that the export of firearms is inextricably intertwined with foreign commerce in firearms… In light of this legislative judgment, we cannot accept petitioner's judgment that the unlicensed export of firearms does not exhibit a business or merchant nature and does not constitute commercial 'dealing' in firearms.” Id.

However, as we will see below in later decisions from the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, questions have been raised about how 22 U.S.C. 2778(b)(2) fits under section 101(a)(43)(C) in light of intervening Supreme Court decisions and other points not raised in Kuhali [see index]. Nevertheless, the decision remains binding in the Second Circuit.

Joseph v. Attorney General of U.S., 465 F.3d 123 (3d Cir. 2006) [PDF version]

The petitioner was convicted in violation of 18 U.S.C. 922(a)(3), which the Third Circuit described as making it “illegal for a person, other than a licensed importer, dealer[,] or manufacturer, to transport into or receive in the state where he resides firearms purchased or otherwise obtained by that person outside his state of residence…” Id. at 124. The BIA had affirmed the immigration judge's opinion that the conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 922(a)(3) was an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C).

The Third Circuit employed the categorical approach after finding that the statute of conviction was not divisible. Id. at 127. The Court concluded that 18 U.S.C. 922(a)(3) “does not include any element of 'dealing in firearms' and, in fact, that it encompasses the legal purchase in another state of a firearm and the subsequent transport of that firearm to the purchaser's home state. Id. at 129. Significantly, the Third Circuit found that the statute of conviction “does not require that the purchase and transportation or receipt of the weapon be accompanied by any intent to sell or otherwise distribute the firearm to another individual.” Thus, because the Third Circuit found that the minimum conduct proscribed by 18 U.S.C. 922(a)(3) was not an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C), the Court found that no conviction under the statute was an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C).

United States v. Guillen-Cruz, 853 F.3d 768 (5th Cir. 2017) [PDF version]

The respondent in this case, like the petitioner in Kuhali, had been convicted in violation of unlicensed export of firearms in violation of 22 U.S.C. 2778. Id. at 771. The Government took the position that this was an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C). Id. However, in the respondent's case, his sentence for illegal entry was enhanced based on a prior violation of 22 U.S.C. 2778(b)(2) and (c), “which prohibit the willful export of Articles on the Munitions List, 22 C.F.R. 121.1, without a license.” Id. The respondent argued that this conviction was not an aggravated felony because he was convicted specifically of exporting high-capacity rifle magazines, which he argued did not fall within the scope of section 101(a)(43)(C). Id. at 771-72. The Government did not contest the respondent's contention, but rather argued that it was not sufficient to meet the respondent's burden on plain error review. Id. at 772.

Here, we will focus only on the question of whether export of high capacity magazines fals within the scope of section 101(a)(43)(C). The Fifth Circuit assessed 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(3), which we discussed earlier in the article for the definition of “firearm” incorporated into section 101(a)(43)(C). The Fifth Ficrcuit explained that “[u]nder the definitions discussed …, a rifle magazine is plainly not a 'firearm' or 'the frame or receiver' of a firearm or a 'muffler or firearm silencer.'” Id. The Court also observed that magazines are not 'destructive device[s]” under 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(4)(A). Id. The Fifth Circuit noted that the closest analogue in the statutes to what the respondent was convicted of was found in 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(4)(B)-(C), which defines as a destructive device “any type of weapon [or combination of parts] … which will, or which may be readily converted to, expel a projectile by the action of an explosive or other propellant, and which has any barrel with a bore or more than one-half inch in diameter.” Id. at 772-73. However, the Fifth Circuit explained that the respondent's conviction “was for export of magazines that hold 7.62x39 millimeter ammunition…” leaving it outside the scope of 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(4)(B)-(C). Id. at 773.

Because the Fifth Circuit found that, because “[t]here is no definition in 18 U.S.C. 841(c) or 921 that, on its face, includes rifle magazines…,” “under the modified categorical approach, enhancing Guillen-Cruz's sentence based on a prior conviction for exporting rifle magazines constituted a clear or obvious error.” Id. Applying the categorical approach more broadly, the Fifth Circuit concluded that the “Articles on the Munitions List include items that clearly do not fit within the relevant definitions…” Id. For this reason, the Court held that “[t]his renders a conviction under 22 U.S.C. 2778(b)(2) and (c) categorically broader than the generic offense, 'illicit trafficking in firearms,' 'destructive devices,' or 'explosive materials.'” For this reason, the Fifth Circuit concluded that the conviction was not an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C).

Because the Fifth Circuit would have held that the respondent's conviction was not an aggravated felony under either the categorical or modified categorical approaches, it did not reach the question of which approach was appropriate. Id. at 771.

Franco-Casasola v. Holder, 773 F.3d 33 (5th Cir. 2014) [PDF version]

The petitioner was convicted of a fraudulent firearms purchase in violation of 18 U.S.C. 554(a). Id. at 35. Specifically, in his immigration hearing, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) submitted evidence that he had conspired to purchase firearms and ammunition for exportation to Guatemala. Id. After the BIA ultimately concluded that the conviction was an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C), the petitioner appealed to the Fifth Circuit.

The Fifth Circuit applied the modified categorical approach to determine whether the petitioner's specific conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 554(a) was an aggravated felony. The Court noted that the statute of conviction “prohibits exporting, buying, selling, and other activities that facilitate the transportation of 'merchandise, article[s], or object[s] contrary to any law or regulation of the United States…'” Id. at 38. The petitioner was convicted specifically for fraudulently purchasing firearms to export to Guatemala. Id. The indictment, to which the petitioner pled guilty, specifically stated that the respondent had purchased five semi-automatic pistols of specific manufacture. Id. at 40. The indictment also identified 22 U.S.C. 2778(b)(2), which includes among its elements that “no defense articles … may be exported or imported without license for such export or import.” Id. Because the indictment specified that the defense articles in questions were firearms, the Board concluded that he had necessarily pled guilty to an offense covered by section 101(a)(43)(C).

United States v. Ochoa, 861 F.3d 1010 (9th Cir. 2017) [PDF version]

The petitioner had been convicted of conspiracy to export defense articles without a license, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 371, and for conspiracy to violate the Arms Export Control Act at 22 U.S.C. 2778. Id. at 1013. He was charged as removable on the basis that his conviction was an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C). However, the issue in the instant case was, subsequent to his illegal reentry, whether his conviction was a predicate offense for sentencing enhancement as an aggravated felony.

To determine whether the conviction was an aggravated felony, the Ninth Circuit applied the categorical approach. Id. at 1015. This was significant because when the alien was initially removed on the charges, the immigration judge had looked to the specific conduct and actions underlying the conviction rather than only at the language of the statute of conviction. Id. at 1012.

The Ninth Circuit explained that the petitioner's statute of conviction, 18 U.S.C. 371, was a generic conspiracy statute. Id. at 1016. In this case, he was convicted for conspiring to violate 22 U.S.C. 2778(b), which prohibits defense articles or defense services designated by the President under the United States Munitions List to be exported or imported without a license. Id. The Court noted that the United States Munitions List includes firearms and ammunition, “but also a vast array of other items…” Id. For this reason, the Court explained that 22 U.S.C. 2778(b) was categorically overbroad with respect to section 101(a)(43)(C), meaning that it covered the export and import of some items that would fall within the scope of section 101(a)(43)(C) and others that would not. Id. Here, the Ninth Circuit noted its agreement with the Fifth Circuit in United States v. Guillen-Cruz, 853 F.3d at 773. The Court “peeked” at the indictment to determine whether the statute of convictions set forth alternative elements or means. Id. at 1017. The count to which the petitioner pled guilty alleged his participation in a conspiracy to export “defense articles, that is, firearms and ammunition, which were designated as defense articles on the United States Munitions List.” Id. The Ninth Circuit determined that the listing of multiple Munitions List items in a single count clearly indicated that they were means of committing a single offense, not elements setting forth distinct offenses. For this reason, the Court ended its inquiry and concluded that the petitioner's conviction was not a categorical aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(C).

Moncrieffe v. Holder, 569 U.S. 184 (2013) [PDF version]

This case dealt with the aggravated felony provision in section 101(a)(43)(B) for certain controlled substance trafficking offenses. The Supreme Court concluded that a conviction for distributing marijuana under a state statute that on its face does not establish that the conduct constituting the offense did not fall under certain exceptions what constitutes the aggravated felony at issue is not an aggravated felony. It referenced section 101(a)(43)(C) with respect to the Government's arguments in the case. It noted that the Government “suggest[ed] that our holding will frustrate enforcement of other aggravated felony provisions, like [section 101(a)(43)(C)]…” Id. at 205. Specifically, the Government was concerned that a state statute that did not specifically exempt antique firearms would be deemed to fall outside the scope of section 101(a)(43)(C) under Moncrieffe. Id. at 206. However, the Supreme Court explained that, under its precedent, there must be a “realistic probability” that the state would apply the statute of conviction to conduct that would fall outside the scope of section 101(a)(43)(C). Id. Thus, “a noncitizen would have to demonstrate that the State actually prosecutes the relevant offense in cases involving antique firearms.” Id.

Conclusion

Section 101(a)(43)(C) is the less common of the two aggravated felony provisions dealing specifically with firearms. However, as our selection of cases show, its use is not unprecedented. The selection of court cases show that one of the live issues involving the provision is the exact scope of the aggravated felony provision with respect to convictions involving 22 U.S.C. 2778. While the Second Circuit took a broad reading in Kuhali, the Fifth and Ninth Circuits have taken narrower views in light of intervening Supreme Court precedent on the categorical review approach [see index].

Finally, it is important to remember that section 101(a)(43)(C) covers conduct that may also be described by other INA provisions. For example, activities that may fall within the scope of section 101(a)(43)(C) may also implicate its neighboring statutes, sections 101(a)(43)(E) and (43)(F). Furthermore, as we noted, section 101(a)(43)(C) covers some conduct that may also fall under section 237(a)(2)(C).

If an alien is charged with an aggravated felony, he or she should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately for case-specific guidance. To learn more about firearms offenses and immigration law, please see our full article index [see index].