- Introduction: Matter of Obshatko, 27 I&N Dec. 173 (BIA 2017)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 173-74

- Relevant Statutes: 27 I&N Dec. at 173-74

- Understanding the Categorical and Modified Categorical Approaches

- Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 175-77

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Obshatko, 27 I&N Dec. 173 (BIA 2017)

On November 17, 2017, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published for-precedent decision in Matter of Obshatko, 27 I&N Dec. 173 (BIA 2017) [PDF version]. In the decision, the Board held that, when determining if a violation of an order of protection renders an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), adjudicators are not governed by the “categorical approach.” Instead, Immigration Judges “should consider the probative and reliable evidence regarding what a State court has determined about the alien’s violation.” Based on its conclusion, the Board clarified its previous published decision in Matter of Strydom, 25 I&N Dec. 507 (BIA 2011) [PDF version], where it had applied the categorical approach section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii).

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of Matter of Obshatko, the Board’s analysis and conclusion, and how the decision will affect similar cases going forward. Please see our companion article on the recent United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit decision in Garcia-Hernandez v. Boente, 847 F.3d 869, 872 (7th Cir. 2017) [PDF version] on the same issue which reached the same conclusion [see article].

Aug. 16, 2018 Update: On August 7, 2018, the Board released a published decision in Matter of Medina-Jimenez, 27 I&N Dec. 399 (BIA 2018). In the decision, the Board followed Matter of Obshatko in a case where the question was whether a conviction fell under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) for purpose of barring an alien from eligibility for cancellation of removal. This extension of Obshatko is notable because in the context of the bar to cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1)(C), a conviction for violating a protection order is required. The fact that a conviction is not required in order to sustain removal charges under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) makes the two issues distinguishable in that respect. To learn more about the Board’s precedent decision in Matter of Medina-Jimenez and how it extends the reasoning in Matter of Obshatko, please see our full article [see article].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 173-74

The respondent, a native and citizen of Uzbekistan, became a lawful permanent resident through adjustment of status on February 6, 2015.

On March 9, 2015, the respondent was convicted of criminal contempt under section 215.51(b)(iii) of the New York Penal Law. His conviction was based on the determination that he had violated an order of protection issued by a New York State court requiring him to stay away from a woman and her family.

Based on the respondent’s conviction, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent, charging him as removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the INA. In removal proceedings, the DHS submitted documents buttressing the charges against the respondent that were not part of the respondent’s record of conviction. These documents included the following:

A presentence report;

A report regarding the respondent’s violation of probation;

A letter from the prosecutor; and

Sworn statements from the respondent’s victims.

The Immigration Judge determined that the foregoing documents could not be considered under either the categorical or modified categorical approach because they were not part of the record of conviction. The Immigration Judge, having discounted the documentary evidence, concluded that the respondent was not removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) for his contempt conviction.

The DHS appealed from the decision to the BIA. It argued that the Immigration Judge erred in applying the categorical and modified categorical approaches to determine whether the respondent was removable. The DHS took the position that the proper approach for determining removability under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) is the “circumstance-specific approach.” The respondent took the position that the Immigration Judge was correct in concluding that the categorical and modified categorical approaches were proper for adjudicating removability under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii).

Relevant Statutes: 27 I&N Dec. at 173-74

There were two statutes at issue in the instant case: The New York State statute of conviction and the INA removability provision under which the respondent was charged.

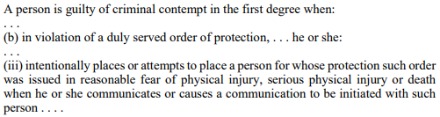

Firstly, the respondent was convicted of violating section 215.51(b)(iii) of the New York Penal Law. The Board excerpted the pertinent part of the statute at the time of the respondent’s conviction as follows:

Secondly, based on that New York conviction, the respondent was charged as removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the INA. Section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) reads as follows:

Any alien who at any time after admission is enjoined under a protection order issued by a court and whom the court determines has engaged in conduct that violates the portion of a protection order that involves protection against credible threats of violence, repeated harassment, or bodily injury to the person or persons for whom the protection order was issued is deportable. For purposes of this clause, the term “protection order” means any injunction issued for the purpose of preventing violent or threatening acts of domestic violence, including temporary or final orders issued by civil or criminal courts (other than support or child custody orders or provisions) whether obtained by filing an independent action or as a pendite lite order in another proceeding.

It is important to note that section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) does not reach every violation of an order of protection. The statute limits the provision to violations of portions of qualifying orders of protections “that involve[] protection against credible threats of violence, repeated harassment, or bodily injury to the person or persons for whom the protection order was issued…”

Understanding the Categorical and Modified Categorical Approaches

Before examining the text of the Board’s analysis and conclusions, it is important to understand the approach that the Immigration Judge undertook. The Board’s analysis focused primarily on why it rejected use of the categorical and modified categorical approaches in adjudicating section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), so we will take a section here to explain how they would have applied in this context.

The categorical approach limits adjudicators to considering only the language of the statute of conviction in comparison to the offense described in the INA. In the instant case, applying the categorical approach would mean that an adjudicator would look only to determine whether the elements required for a conviction in violation of section 215.51(b)(iii) of the New York Penal Law were a “categorical match” with section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). That is, if any conduct that could lead to a conviction in violation of section 215.51(b)(iii) would fall under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), then the conviction would render the respondent removable. However, if the New York Penal Law provision was “categorically overbroad,” that is, covered more conduct than section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), no conviction under the New York Penal Law provision would render an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii).

An adjudicator may use the “modified categorical approach” if a statute is “divisible,” meaning that the statute of conviction lists distinct offenses in the disjunctive, or more simply put, if the statutes lists separate and distinct alternative conduct that qualify for conviction under the statute. When employing the modified categorical approach, an adjudicator is permitted to refer to the record of conviction for the sole and limited purpose of determining which part of the statute of conviction the alien violated. Upon determining which part of the statute the alien was convicted in violation of, the adjudicator must then use the methods associated with the categorical approach when comparing it to the relevant INA provision.

The categorical approach does not permit any reference to the record of conviction except for the limited purpose of determining whether the categorical or modified categorical approach is appropriate [see article]. The modified categorical approach permits reference to the record of conviction for the limited purpose of determining which portion of a divisible statute was violated. Notably, neither approach permits reference to evidence outside of the record of conviction, which the DHS sought to rely upon in the instant case. As we will see, the DHS argued for the circumstance-specific approach, which allows for more evidence to be consulted in order to learn more about the context of the criminal act (see below for examples). However, as we will discover, the Board explained that the circumstance-approach applies where a statutory provision is generally subject to categorical analysis but a portion of it is not. 27 I&N Dec. at 176.

To learn about the categorical approach, please see our compendium on a collection of administrative and judicial decisions on the subject [see article]. To learn about the circumstance-specific approach in other cases, please see our articles on Matter of Garza-Oliveras, 26 I&N Dec. 736 (BIA 2016) [see article] (failure to appear) and Matter of H. Estrada, 26 I&N Dec. 749 (BIA 2016) [see article] (domestic violence), and the Adam Walsh Act [see section].

Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 175-77

First, the Board concluded from its analysis of “the plain language of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii)” that a “conviction” is not an element of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). This means that, while a finding by a state court of a violation of an order of protection may result in a conviction under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) , an alien could be determined to be removable under the provision absent such a conviction provided that “the court determines” that the alien had violated a qualifying portion of the order of protection (note: “court” means the state court that had issued the order of protection, not an immigration court).

Following its determination that section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) does not require a “conviction,” the Board framed the issue before it in Matter of Obshatko as follows:

The issue before us, therefore, is whether the fact of an alien’s conviction requires the application of the categorical and modified categorical approaches in determining removability under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), even though the statutory language clearly indicates that no conviction is necessary for the alien to be removable.

The Board quoted from the Supreme Court of the United States decision in Mellouli v. Lynch, 135 S.Ct. 1980, 1986 (2015) [PDF version], which stated that the categorical approach is “[r]ooted in Congress’ specification of conviction, not conduct, as the trigger for immigration consequences.” However, as it had explained, the Board determined that a “conviction” is not necessary under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). Accordingly, the Board concluded that “[Congress] did not intend an alien’s removability under [section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii)] to be analyzed under either the categorical or modified categorical approach.” To this effect, the Board explained that the categorical and modified categorical approaches place limitations on the types of evidence that may be considered by an adjudicator. The Board took the position that requiring the categorical and modified categorical approaches in cases where an alien was convicted of violating a protection order would mean that, under certain circumstances, an alien who was convicted of violating a protection order “may be entitled to a more favorable outcome than an alien whose violation did not result in a conviction.”

The Board found support for its conclusion regarding the inapplicability of the categorical and modified categorical approaches in multiple Federal appellate court decisions. In Garcia-Hernandez v. Boente, 847 F.3d 869, 872 (7th Cir. 2017) [PDF version], the Seventh Circuit held that “neither the categorical approach nor the modified categorical approach controls” in determining removability under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the INA. Like the Board, the Seventh Circuit reasoned from the fact that a “conviction” is not required by the text of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). The Board agreed with the Seventh Circuit’s determination in Garcia-Hernandez, 847 F.3d at 872, that in determining removability under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), “[w]hat matters” “is simply what the state court ‘determined’ about [the alien’s] violation of the protection order.” Please see our companion article to learn more about the Garcia-Hernandez decision [see article].

Matter of Obshatko arose in the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Accordingly, the Board would be bound by any relevant Second Circuit precedent on the issues addressed. The Board also found the Second Circuit decision in Hoodho v. Holder, 558 F.3d 184, 189 n.2 (2d Cir. 2009) [PDF version], instructive to the effect that it held that “[n]ot every removability provision requires application of the ‘categorical approach’ or the ‘modified categorical approach.’” Interestingly, at 27 I&N Dec. at 175-76 n.3, the Board noted that, in Hoodho, the Second Circuit had applied the modified categorical approach in a case involving section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). However, the Board read Hoodho as not resolving whether the application of the categorical or modified categorical approach was required for adjudicating section 237(a)(2)(E)(iii), and noted that the alien’s argument in that case had simply assumed that 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) adjudications were undertaken through application of the approaches.

Having agreed with the Seventh Circuit that neither the categorical nor modified categorical approaches control in the section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) context, the Board nevertheless disagreed with the DHS’s contention that the “circumstance-specific approach” controls. The Board explained that the circumstance-specific approach “applies only when a portion of a criminal ground of removability is not subject to the categorical approach.” To this effect, it cited to the Supreme Court decision in Nijhawan v. Holder, 557 U.S. 29, 40 (2009) [PDF version], which applied the circumstance-specific approach to section 101(a)(43)(M)(i) insofar as it was necessary to assess “the specific circumstances surrounding an offender’s commission of a fraud and deceit crime.” Here, and contrary to the aggravated felony provision at issue in Nijhawan, because the Board had determined that section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) is not subject to categorical analysis, the provision is not subject to categorical analysis, the circumstance-specific approach is inapplicable.

However, the Board held that, while application of the circumstance-specific approach was not appropriate in the section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) context, “in practical terms, the result in this case may be the same under the circumstance-specific approach, since both the specific circumstances surrounding an alien’s violation and what a court has ‘determined’ regarding that violation may be established through any reliable evidence.” In Matter of H. Estrada, 26 I&N Dec. at 753, the Board explained that “any reliable evidence” may be considered when applying the circumstance-specific approach. In Matter of D-R-, 25 I&N Dec. 445, 458 (BIA 2011) [see article], remanded on other grounds sub nom., Radojkovic v. Holder, 599 F.App’x 646 (9th Cir. 2015), the Board held that “[i]n immigration proceedings, the ‘sole test for admission of evidence is whether the evidence is probative and its admission is fundamentally fair.’”

Finally, the Board articulated its new general rule. First, it held “that whether a violation of a protection order renders an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the [INA] is not governed by the categorical approach, even if a conviction underlies the charge.” Second, the Board held that “an Immigration Judge should consider the probative and reliable evidence regarding what a State court has determined about the alien’s violation.” Third, the Board directed that, in assessing the State court’s determination, the Immigration Judge must consider:

1. “[W]hether a State court ‘determine[d]’ that the alien ‘has engaged in conduct that violates the portion of a protection order that involve[d] protection against credible threats of violence, related harassment, or bodily injury’”; and

2. “[W]hether the order was ‘issued for the purpose of preventing violent or threatening acts of domestic violence.’”

Based on its conclusion in the instant case, the Board opted to clarify its decision in Matter of Strydom, 25 I&N Dec. 507 (BIA 2011) [PDF version]. Matter of Strydom also involved a respondent who was charged as removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) for having violated a protection order. In that case, because neither party had raised the correctness of applicability of the categorical approach as an issue, the Board had assumed that it applied in considering the case, ultimately finding that the respondent in Matter of Strydom was removable. However, in the instant case, the applicability of the categorical approach was the central issue, and the Board determined that it does not apply. The Board stated that “[a]ccordingly, we will not apply the categorical approach in this or any future cases involving section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the [INA].”

Interestingly, the Board also cited in a footnote to its decision in Matter of Gonzalez-Zoquiapan, 24 I&N Dec. 549 (BIA 2008) [PDF version]. That case involved the prostitution inadmissibility provision in section 212(a)(2)(D)(ii), which, like section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), does not require a conviction. In the footnote at 27 I&N Dec. at 177 n.3, the Board stated that although it had, in a similar manner to Matter of Strydom, applied the categorical approach in Matter of Gonzalez-Zoquiapin, it had done so “because the only evidence of removability was the alien’s conviction documents.” From this it can be anticipated that the Board will reach a similar result in any future case addressing removability under section 212(a)(2)(D)(ii) as it reached in the instant case.

In applying its conclusion to the instant case, the Board held that the Immigration Judge erred in applying the categorical approach to determine whether the respondent was removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). Accordingly, the Board sustained the DHS’s appeal and vacated the Immigration Judge’s decision to terminate proceeding and remanded the record for further consideration of the respondent’s removability consistent with the Board’s decision. The Board instructed the Immigration Judge to “admit and consider all the probative and reliable evidence that relates to the respondent’s violation of the protection order and accord it the appropriate weight.”

Conclusion

In practical terms, the Board’s decision in Matter of Obshatko gives section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) broader reach by holding that Immigration Judges are not bound by the categorical or modified categorical approaches. In the event that an alien is charged as removable under the provision based on a conviction for violating an order of protection, adjudicators may consider all “probative and reliable evidence regarding what a State court has determined about the alien’s violation.” This holding will allow the Government to establish removability in certain cases where it would not have been able to had Immigration Judges been bound to apply categorical analysis to the statute of conviction.

This issue will be worth watching going forward to see if appellate courts defer to the Board’s decision. The Board noted that the Seventh Circuit had adopted this approach in Garcia-Hernandez v. Boente, 847 F.3d 869, 872 (7th Cir. 2017). However, it is certainly possible that other circuits may reach a different conclusion on the issue. We will update the site with more information as it becomes available.

The case highlights that it is imperative that aliens carefully comply with any applicable orders of protection. An alien facing charges of removability or who has questions about how a criminal issue may affect immigration status should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately for case-specific guidance.