- Introduction: Matter of Medina-Jimenez, 27 I&N Dec. 399 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 399-400

- Board Concludes that Categorical Approach Does Not Govern INA 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in Cancellation Context: 27 I&N Dec. at 401

- Further Discussion of “Conviction” Requirement in Cancellation Context: 27 I&N Dec. at 401-03

- Applying Rule to Facts of Instant Case: 27 I&N Dec. at 403-04

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Medina-Jimenez, 27 I&N Dec. 399 (BIA 2018)

On August 7, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published decision of Matter of Medina-Jimenez, 27 I&N Dec. 399 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. The Board’s task was to decide the proper approach for evaluating whether a conviction for violating an order of protection falls under the deportability provision at section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which causes an alien to be ineligible for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1)(C). The Board held that the categorical approach, which restricts adjudicators to assessing the language of the statute of conviction rather than the individual’s underlying criminal conduct, does not govern whether violating a protection order falls within the scope of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). The Board held that when considering whether a conviction for violating an order of protection renders an applicant ineligible for cancellation of removal, immigration judges must determine (1) whether the alien has been convicted within the INA’s definition of the term conviction under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA; and (2) whether the conviction was for violating an order of protection within the meaning of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii).

Regarding how to determine whether a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), the Board followed its recent precedent decision in Matter of Obshatko, 27 I&N Dec. 173 (BIA 2017) [PDF version]. The instant decision is a noteworthy extension of Matter of Obshatko because Obshatko dealt with section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in a case where it was the basis of a removal charge, in which context a conviction is not required. In the context of rendering an alien ineligible for cancellation of removal, a conviction is required.

In this article, we will examine Matter of Medina-Jimenez, how it follows Matter of Obshatko [see article], and what the decision means going forward for cancellation of removal applicants. To see a full list of all of our articles on immigration precedent decisions, please see our comprehensive index [see index].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 399-400

The respondent, a native and citizen of Mexico, claimed that he entered the United States without inspection in 1995.

On July 28, 2010, the respondent pled guilty to contempt of court for violating a protection order issued by an Oregon Circuit Court. As a result of his guilty plea, “[h]e was sentenced to 7 days in jail, fined, and placed on probation for 18 months.”

On July 30, 2010, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued the respondent a Notice to Appear (NTA), initiating removal proceedings. The DHS charged the respondent as inadmissible under section 212(a)(6)(C)(i) of the INA as an alien who was present in the United States without being admitted or paroled.

Before an Immigration Judge in removal proceedings, the respondent conceded that he was removable as charged. However, he filed an application for cancellation of removal. On December 13, 2011, the Immigration Judge denied the respondent’s application for cancellation of removal on the basis of his contempt of court conviction. Specifically, the Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent’s contempt of court conviction was a conviction for violating an order of protection under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the INA, which functions as a bar to eligibility for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1)(C).

The respondent appealed from the Immigration Judge’s decision to the Board, but the Board denied the appeal on September 14, 2013.

The respondent then filed a motion with the Oregon court to “correct the original judgment entered with regard to his violation of a protection order.” On October 9, 2014, the respondent’s request was granted, and the Oregon court issued a “General Judgment of Contempt,” nunc pro tunc from the date of the original order, giving the correction retroactive effect under Oregon law to the date of the original order. The result of the change was that under Oregon law, the respondent no longer had a “conviction,” but rather a “contempt of court” judgment.

The respondent had appealed from the Board’s unpublished decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. On January 27, 2015, the Ninth Circuit granted the government’s unopposed motion for remand to the Board so that the Board could determine whether the respondent’s new judgment affected his eligibility for cancellation of removal.

On July 14, 2015, the Board concluded that, despite the fact that the respondent’s judgment was no longer that he had committed a “crime,” the contempt offense was still processed under Oregon law as “punitive,” and therefore still constituted a “conviction” under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA. For this reason, the Board again concluded that the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal.

The respondent again appealed to the Ninth Circuit. While the appeal was pending, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its decision in Mathis v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2243 (2016) [PDF version], which joined its prior decision in Descamps v. United States, 570 U.S. 254 (2013) [PDF version]. Both cases dealt with the proper application of what is called the “categorical approach,” an approach which limits adjudicators to looking at the language of a statute of conviction rather than the underlying facts of the actual criminal conduct that led to the conviction. To learn more about the issue, please see our articles on Mathis [see article], Descamps [see article], and our series of articles on recent BIA decisions interpreting these decisions [see index]. The Ninth Circuit again granted the Government’s unopposed motion for remand to the Board, this time to address the potential effect of Mathis and Descamps on the Board’s conclusion that the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal. On remand, the Ninth Circuit directed the Board to consider whether the categorical approach, circumstance-specific approach [see article], or some other approach entirely should be employed “in determining whether an alien is ineligible for cancellation of removal under [section 240A(b)(1)(C)], for having been “convicted of an offense under section … [237(a)(2)(E)(ii)]…” Furthermore, the Ninth Circuit also asked the Board to weigh in, “if necessary,” on whether it believed that the same approach that is employed in the context of determining whether an alien is ineligible for cancellation of removal should be employed in determining if the alien is removable for a conviction under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). Here, it is important to note that an alien may be charged as removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) [see section].

While the case was pending on remand, the Board handed down a published decision in Matter of Obshatko, 27 I&N Dec. 173 (BIA 2017) [see article]. In Obshatko, the Board held that neither the categorical approach nor the circumstance-specific approach governs when determining whether a conviction for violating an order of protection falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the context of removal charges under that provision. In a separate case, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Rodriguez v. Sessions, 876 F.3d 280 (7th Cir. 2017) [PDF version], reached the same conclusion regarding section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the context of a conviction constituting a bar to eligibility for cancellation of removal. The Board asked the parties to provide supplemental briefing in the instant case in light of Obshatko and Rodriguez. The respondent, who submitted briefs prior to Obshatko, argued that the categorical approach was the proper approach to determining whether a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) and causes ineligibility for cancellation of removal. The Government argued that the Board should apply Matter of Obshatko to the instant case.

Board Concludes that Categorical Approach Does Not Govern INA 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in Cancellation Context: 27 I&N Dec. at 401

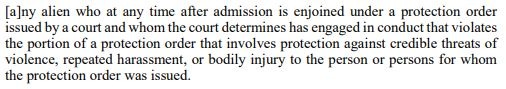

Under section 240A(b)(1)(C) of the INA, an alien who has been convicted of an offense under section 212(a)(2), 237(a)(2) [see article], or 237(a)(3) [see article] is ineligible for cancellation of removal. The respondent’s application for cancellation was denied on the basis of a conviction under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). The Board excerpted the pertinent part of the statute:

In Matter of Obshatko, the Board addressed section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the context of an alien who was charged with removability under the provision [see section]. There, it held that the plain language of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) made clear that an alien can be found to have violated an order of protection for immigration purposes even if he or she was not convicted of violating an order of protection. In Obshatko , however, the alien had been convicted of violating an order of protection, so the question before the Board was whether the restrictive categorical approach or circumstance-specific approach applied to determining whether such a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). The Board concluded that these determinations are “not governed by the categorical approach, even if a conviction underlies the charge.” The fact that an alien could be found removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) absent a conviction was significant to the Board’s statutory analysis in Obshatko. Notably, regarding ineligibility for cancellation of removal, an actual conviction is required, making the issue distinguishable in that aspect from section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the removal context.

The instant case, like Matter of Obshatko, involved the question of whether a conviction for violating an order of protection was an offense described by section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). However, the question here was whether the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal due to being covered by section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) rather than whether he was removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). Thus, the Board was left to determine whether Matter of Obshatko’s reasoning extends to determining whether a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) for purpose of rendering an alien ineligible for cancellation of removal.

The Board concluded that “the categorical approach does not apply when deciding whether an alien’s violation of a protection order renders him ‘convicted of an offense’ for purposes of section 240A(b)(1)(C).” Quoting from Matter of Obshatko, 27 I&N Dec. at 176-77, the Board held that “an Immigration Judge should consider the probative and reliable evidence regarding what a State court has determined about the alien’s violation.” Thus, the Board simply extended Matter of Obshatko to the instant issue in full, formally standardizing its approach to section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the removal context and in the context of eligibility for cancellation of removal. We discuss the Obshatko rule in detail in our article on that decision [see article]. In short, the Board held that when determining whether a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), Immigration Judges should assess the “probative and reliable evidence” to determine what the court below had determined about the alien’s conduct and whether those determinations render the alien subject to section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii).

Further Discussion of “Conviction” Requirement in Cancellation Context: 27 I&N Dec. at 401-03

The Board explained that there are “two distinct inquiries” in determining whether a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), thereby rendering an alien ineligible for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1)(C). An Immigration Judge must first determine whether the offense resulted in a “conviction,” as defined in section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA. The Board explained that the question of whether an offense resulted in a conviction “is a distinct inquiry” from the question of whether to apply the categorical approach. Second, the Immigration Judge must assess whether the State court found that the alien “engaged in conduct that violates a portion of a protection order that involves protection against credible threats of violence, repeated harassment, or bodily injury to the person or persons for whom the protection order[] was issued.” Immigration Judges may refer to “probative and reliable evidence,” in accord with Matter of Obshatko. The Board held that “[a]n Immigration Judge might reasonably conduct these two inquiries-neither of which involves the elements-based categorical approach-in either order.”

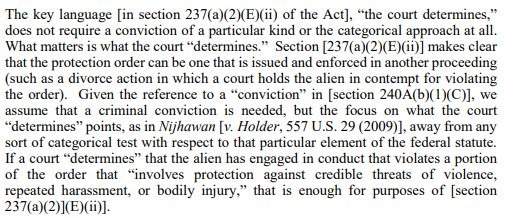

As we noted above, the Seventh Circuit rejected the argument that the categorical approach governs determining whether an “offense under” section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) is an offense that bars cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1)(C). The Seventh Circuit reached the same result in a separate decision, Garcia-Hernandez v. Boente, 847 F.3d 869, 872 (7th Cir. 2017) [PDF version], from which the Board quoted the following excerpt in its decision:

Before continuing, it is worth noting that the Board acknowledged the Seventh Circuit’s reference in the foregoing passage to the Supreme Court decision in Nijhawan v. Holder, 557 U.S. 29 (2009) [PDF version] [see article]. In Nijhawan, the Supreme Court held that the circumstance-specific approach governs assessing the amount of loss to victims for determining whether a conviction falls under section 101(a)(43)(M). In Obshatko, the Board explicitly distinguished the circumstance-specific approach from its approach for determining whether a conviction falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), while noting they may, in many cases, lead to the same outcome. The Board stood by its conclusion on this point in Obshatko.

The Board found further support for its reading of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the cancellation eligibility context in the Ninth Circuit decision in Gonzalez-Gonzalez v. Ashcroft, 390 F.3d 649, 652 (9th Cir. 2004) [PDF version]. In that case, the Ninth Circuit held that section 240A(b)(1)(C) covers aliens who have been “convicted of an offense described under” sections 212(a)(2), 237(a)(2), or 237(a)(3). The Board held that if the evidence supports that the respondent’s offense is described under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), “section 240A(b)(1)(C) is satisfied by evidence that the offense resulted in a conviction.”

The Board rejected the view that the “conviction” requirement in section 240A(b)(1)(C) means that the categorical approach must govern section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the cancellation of removal context. While the Board acknowledged that a conviction is necessary in the cancellation of removal context but not in the removal context, it concluded that “it would be incongruous to apply the elements-based categorical approach to section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), which focuses on a court’s determination regarding an alien’s conduct,” echoing the Seventh Circuit’s similar conclusion in Garcia-Hernandez, 847 F.3d at 872. Instead, the Board concluded that, provided that the respondent was “convicted” within the definition of section 101(a)(48)(A), the same approach to determining whether the judge’s findings fell under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) applies in both the cancellation of removal and removal contexts.

Applying Rule to Facts of Instant Case: 27 I&N Dec. at 403-04

Finally, the Board moved to apply its rule to the facts of the specific case before it.

First, the Board declined to reconsider its June 14, 2015 conclusion that the respondent’s offense resulted in a “conviction” within the meaning of section 101(a)(48)(A). It noted that the Ninth Circuit had not directed it to reconsider the issue.

Regarding the instant facts, the Board found that “[t]he record includes reliable and uncontested evidence that the respondent was convicted of an offense under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) of the [INA].” Specifically, “[t]he judgment of the Oregon court states that the respondent was convicted of contempt of court. It further indicates that the conviction was based on his guilty plea to an information charging that he ‘did unlawfully and willfully disobey a restraining order filed under the Family Abuse [Prevention] Act of the Jefferson County Circuit Court by entering and remaining or attempting to enter and remain within 150 feet of [the protected victim’s] residence.” The Board found that the Oregon court “clearly determined that the respondent’s underlying conduct involved a violation of the ‘stay-away’ provision in a protection order issued pursuant to the Oregon Family Abuse Prevention Act…” The Board added in a footnote that the amended judgment issued by the Oregon court in the instant case stated that the respondent was “found in violation of a restraining order on … Count number 1, Contempt of Court, ORS 33.015.”

The Board noted that the Oregon Family Abuse Prevention Act is designed to “protect victims against threats of domestic violence,” citing to Szalai v. Holder, 572 F.3d 975, 978 n.2 (9th Cir. 2009) [PDF version], wherein the Ninth Circuit wrote that the purpose of the law “is to prevent acts of family violence through restraining orders.” In Szalai, 572 F.3d at 982, the Ninth Circuit wrote that the Family Abuse Prevention Act “involves protection against credible threats of violence, repeated harassment, or bodily injury” within the meaning of section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii). The Board relied on Ninth Circuit precedent on the issue in its own published decision in Matter of Strydom, 25 I&N Dec. 507, 510 (BIA 2011) [PDF version], wherein it held that “the primary purpose of a no-contact order is to protect the victims of domestic abuse from the offender.”

Because the Board concluded that the Immigration Judge was correct in determining that the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal because he was convicted of an offense under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii), it dismissed the respondent’s appeal.

Conclusion

In Matter of Medina-Jimenez, the Board applied the same approach that it had applied to determining whether a conviction is for violating a protection order falls under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) in the removal context to determining whether a conviction falls under the same provision in the cancellation context. Thus, the only difference between section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) as a removal charge and as a bar to cancellation of removal is that the latter requires a conviction within the definition of section 101(a)(48)(A), whereas the former does not. However, provided that the alien was convicted, the inquiry is the same whether he or she is charged as removable under section 237(a)(2)(E)(ii) or is applying for cancellation of removal.

An alien in removal proceedings should always consult with an immigration attorney for case-specific guidance. As both Matter of Medina-Jimenez and Matter of Obshatko show, the question of whether a conviction supports an alien’s removability or eligibility for relief from removal may hinge on very technical legal questions, such as the approach that the adjudicator should take to evaluating the relevant statutes.

As we discuss in our article on Matter of Obshatko, certain violations of protection orders can be the basis for removal charges. In an additional note, it is important for aliens to bear in mind that violating protection orders can lead to serious immigration repercussions, especially when they are issued in the domestic violence context. Thus, an alien should adhere strictly to any orders of protection no matter what circumstances may exist in the specific case.