Introduction

On November 16, 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions released a memorandum to the entire Department of Justice (DOJ) titled “Prohibition on Improper Guidance Documents” [PDF version]. In the memorandum, Attorney General Sessions prohibited the issuance of DOJ guidance documents that have the effect of circumventing the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) or effectively creating new law. In this article, we will review the memorandum and examine what it may mean going forward. You may also read the DOJ’s news release on the memorandum here [PDF version].

Furthermore, Attorney General Sessions discussed this and related issues in a recent speech to a gathering of the Federalist Society. We have embedded the speech, courtesy of the Federalist Society YouTube channel, for your convenience:

Overview of Rulemaking

Like any other Federal agency, the DOJ is bound by laws, which are enacted by Congress and signed by the President. The DOJ may then issue regulations o rules that are necessary in order to implement these laws. Under the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), these regulations must be promulgated through notice-and-comment rulemaking. This means that an agency will propose a regulation, give the public a period of time in which to comment, and then take the comments into account in creating a final regulation. For an example, please see our recent article on a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) proposed rule on the EB5 immigrant investor program [see article].

Agencies often issue guidance documents in lieu of new regulations. Attorney General Sessions’ memorandum is concerned with ensuring that these guidance documents are limited in scope and do not function to create binding rules purporting to bind individuals outside of the department that should, under law, undergo notice and comment rulemaking. On site, we have many articles that discuss memoranda of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). These memoranda are examples of guidance documents that do not purport to be regulations, but that may in some cases have similar effects.

Perhaps the most prominent example of a debate over the propriety of an agency memorandum concerns the recent litigation surrounding the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) programs. Both DACA and DAPA were implemented through DHS memoranda rather than through notice-and-comment rulemaking. This point was central to Texas’ argument against DAPA, which was well received by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit [see opinion blog]. Ultimately, when the Trump Administration rescinded the DAPA [see article] and DACA [see article] memoranda, it accepted the arguments that the previous administration had exceeded its authority in part because it had implemented what the Trump Administration considered to be binding rules outside the auspices of the APA. Unsurprisingly, Attorney General Sessions himself cited this as one of the reasons for his determining that DACA was illegal [see article].

However, the Sessions memorandum that we are discussing in this article applies only to the DOJ, not to the DHS or U.S. Department of State (DOS). For immigration watchers, it is worth noting that the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is part of the DOJ.

Examining the Text of the Memo

Attorney General Sessions stated that “[i]n promulgating regulations, the [DOJ] must abide by constitutional principles and follow the rules imposed by Congress and the President.” He noted two of the most important requirements.

First, he explained, the DOJ has “the fundamental requirement” to “regulate only within the authority delegated to [it] by Congress.” In short, the Attorney General here notes that only Congress can write and enact laws. Although the President has the power to sign or veto laws, the Executive Branch, of which the DOJ is part, does not have lawmaking authority. Rather, it is empowered to execute the laws enacted by Congress and signed by the President. Accordingly, regulations promulgated by Executive Branch agencies must not exceed the authority delegated by Congress.

Second, the Attorney General emphasized “the [APA’s] requirement to use, in most cases, notice-and-comment rulemaking when purporting to create rights or obligations binding on members of the public or the agency.” As we discussed earlier, the APA requires binding rules to undergo notice-and-comment rulemaking. In conjunction with his first point, we come to understand that binding rules may not exceed the authority that Congress delegated and they must be promulgated through the proper procedures outlined in the APA. Sessions argued that the APA has an additional benefit of “availing agencies of more complete information about a proposed rule’s effects than the agency could ascertain on its own…”

Attorney General Sessions noted that “[n]ot every agency action is required to undergo notice-and-comment rulemaking.”

The Attorney General listed three examples of cases where guidance would be appropriate and lawful:

Guidance and similar documents to educate regulated parties through plain-language restatements of existing legal requirements;

Guidance providing non-binding advice on technical issues through examples; or

Guidance consisting of practices to assist in the application or interpretation of statutes and regulations.

He then listed three examples of cases where guidance would be inappropriate:

Guidance that is a substitute for rulemaking;

Guidance that Imposes new requirements on entities outside the Executive Branch; or

Guidance that creates binding standards by which the DOJ will determine compliance with existing regulatory or statutory requirements.

Attorney General Sessions then stated that it has come to his attention “that the [DOJ] has in the past published guidance documents-or similar instruments of future effect by other names, such as letters to regulated entities-that effectively bind private parties without undergoing the rulemaking process.” In short, he took the position that the DOJ has, in the past, issued new binding rules disguised as guidance and, by doing so, has circumvented the proper rulemaking procedures required by the APA.

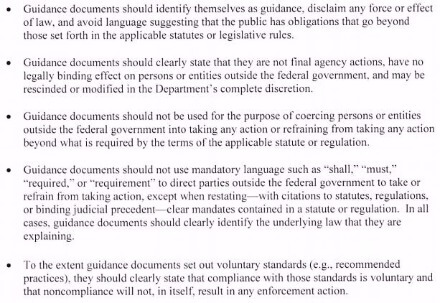

Attorney General Sessions then stated that the DOJ will no longer engage in the practice of issuing guidance documents that have the effect of binding private parties without undergoing the rulemaking process required by the APA. To ensure that the DOJ follows this directive, the Attorney General listed the six following principles for all DOJ components to follow in issuing guidance documents:

[Click image to view full size]

The effect of these six principles is to ensure that guidance documents do not circumvent the proper legal procedures for implementing binding rules. In addition to these six principles, Attorney General Sessions also directed the DOJ to implement them in a manner consistent with the policies of the Office of Management and Budget, with specific reference to its Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices, 72 FR 3432 (Jan. 25, 2007) [PDF version].

Interestingly, the memorandum does not only apply to future guidance. Attorney General Sessions directed the Associate Attorney General, currently Rachel Brand, “to work with components to identify existing guidance documents that should be repealed, replaced, or modified in light of these principles.” Considering that the Attorney General himself took the position that the DOJ has not always followed the rules he set forth for the issuance of guidance documents, it seems quite likely that certain past guidance documents will be “repealed, replaced, or modified” as a result of this review.

Attorney General Sessions explained that the “guidance documents” affected by the memorandum “include any [DOJ] statements of general applicability and future effect, whether styled as guidance or otherwise that are designed to advise parties outside the federal Executive Branch about legal rights and obligations falling within the [DOJ’s] regulatory or enforcement authority.”

However, Sessions stated that the following types of actions and documents are not affected by the memorandum:

Adjudicatory actions that do not have the aim or effect of binding anyone beyond the parties involved;

Documents informing the public of the DOJ’s enforcement priorities;

Documents listing factors the DOJ considers in exercising its prosecutorial discretion;

Internal directives, memoranda, or training materials for DOJ personnel directing them on how to carry out their duties;

Positions taken by the DOJ in litigation; or

Advice provided by the Attorney General or the Office of Legal Counsel.

In short, this internal memorandum only addresses guidance or other documents or actions that advise parties outside of the Executive Branch about legal rights and obligations falling under the DOJ’s authority. In short, guidance that may describe binding rules for those outside of the DOJ will no longer be issued by DOJ.

Conclusion

The memorandum is noteworthy in that it seeks to constrain the actions of an Executive department -the DOJ — in issuing guidance that purports to bind individuals outside of the department. Attorney General Sessions advocated against what he sees as excesses in “guidance documents” in other departments too, such DACA promulgated by the DHS, and the “dear colleague” letters sent by the Department of Education on several issues during the previous administration.

There are three points that bear watching going forward.

First, it will be worth watching to see what kind of effect the new guidance has on how the DOJ functions in the future. In the press release, Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand acknowledged that “[t]he notice-and-comment process that is ordinarily required for rulemaking can be cumbersome and slow…” It is important to note that she, like the Attorney General, took the position that this is a feature of the rulemaking procedure, not a bug. However, it is certainly possible, if not likely, that DOJ actions that were previously implemented through guidance documents or through “sue and settle” policies may now undergo the more rigorous and slower processes set forth in the APA.

Second, it will be important to monitor the results of the DOJ’s review of previous guidance documents. It seems inevitable from the text of the memorandum that many guidance documents in effect today will be subject to scrutiny under the review. The rescission or modification of these documents could have significant effects in certain cases. For immigration-watches, it will be important to take note if the DOJ rescinds or modifies any guidance relating to the EOIR.

Finally, as noted by Josh Blackman in National Review Online, Attorney General Sessions is not the only person in the Trump Administration who is taking an aggressive line on limiting the use of “guidance” documents [link].1 The White House Counsel, Donald McGhan, also addressed the Federalist Society gathering where Attorney General Sessions spoke, and he discussed many of the same themes. In his post, Blackman suggested that the policy implemented by Attorney General Sessions could be implemented across the Executive Branch by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which is headed by Neomi Rao. The extension of this policy could have a significant effect on the DHS, which has over the years made extensive use of policy memoranda.

We will continue to monitor the issue and update the site of the policies in the Sessions memoranda are either extended to the entire Trump Administration or to other agencies that have a role in immigration policy. We will post more about interesting issues involving administrative law and procedure in the Trump Administration in the coming weeks and months. For more on the issues, please see a collection of articles and blogs on now-Justice Neil Gorsuch and the issue of Chevron deference [see article].