Introduction

On September 5, 2017, the Acting Secretary of Homeland Security, Elaine C. Duke, issued a memorandum rescinding the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Please see our full article for an in-depth look at the reasoning and the practical immigration effects of the decision [see article]. In this article, we will examine the legal justification for the decision espoused in the recommendation of Attorney General Jeff Sessions that DACA is illegal. We will also examine an interesting note in Acting Secretary Duke’s memorandum rescinding DACA that appears to concede one of the points made by Texas in the litigation against the erstwhile Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) program.

The Sessions Letter

Attorney General Jeff Sessions wrote a letter to Acting Secretary Duke advising her that the DACA program was illegal and that DACA should be rescinded. You may see the full letter here [PDF version].

Attorney General Sessions stated that “DACA was effectuated by the previous administration through executive action, without proper statutory authority and with no established end-date, after Congress’ repeated rejection of proposed legislation that would have accomplished a similar result.” He described it as “an open-ended circumvention of immigration laws and an unconstitutional exercise of authority by the Executive Branch.”

Attorney General Sessions noted that the similar — albeit more far-reaching — DAPA program had been enjoined on a nationwide basis by a Federal district court. The injunction was subsequently affirmed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and then by the Supreme Court of the United States by a divided 4-4 vote. See Texas v. United States, 86 F.Supp 3d 591, 699-70 (S.D. Tex.) [PDF version], aff’d, 809 F.3d 134, 171-186 (5th Cir. 2015) [PDF version], aff’d by equally divided Court, 136 S.Ct. 2271 (2016) [PDF version]. Subsequently, the former Secretary of Homeland Security, John Kelly, rescinded DAPA in June, citing to the adverse court decisions [see article]. Attorney General Sessions determined that, because DACA “has the same legal and constitutional defects that the court recognized as to DAPA, it is likely that potentially imminent litigation would yield similar results with respect to DACA.”

As we will discuss, both the District Court for Southern District of Texas and the Fifth Circuit analyzed the implementation of DACA in order to ascertain how DAPA would be implemented, before ultimately finding that DAPA should be enjoined because Texas was ultimately likely to succeed on the merits of its claims.

Attorney General Sessions concluded that in his capacity as U.S. Attorney General, “I have a duty to the Constitution and to faithfully execute the laws passed by Congress.” He cited to President Donald Trump in stating that the proper enforcement of the immigration laws is “critical to the national interest and to the restoration of the rule of law in our country.”

Analysis of Attorney General Session’s Note on Role of Attorney General

Before examining specific legal issues regarding DACA, it is worth noting the following passage of Attorney General Sessions’ letter:

I have a duty to the Constitution and to faithfully execute the laws passed by Congress.

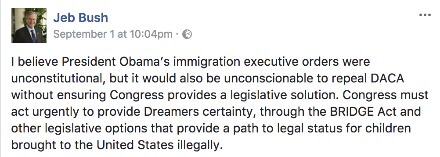

The majority of Republican politicians have generally expressed the opinion that DACA was an unlawful exercise of executive authority. However, many of these same Republicans support the policy goals of DACA when viewed separately from the manner of its implementation. Many Republicans in the latter camp urged President Trump to defend DACA in court while Congress works on a legislative solution through the proper legal channels. To cite to just one of many examples, one of President Trump’s primary opponents, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, issued the following statement on his Facebook page prior to the final decision:

Here, Bush argued that:

1. DACA is unconstitutional; but

2. DACA should remain in place as long as Congress does not provide a legislative solution.

To be clear, there are many arguments on both sides of the question of DACA’s legality. For the purpose of this section, we are examining the issue from the starting point of assuming that DACA was illegal.

Bush articulated a policy-oriented approach. Although he believes that DACA was illegal, he nevertheless believed that policy and, perhaps, moral, considerations outweighed ending the program without legislation enshrining its goals in law. Many others, such as Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, advanced similar positions. A similar variant of this position adopted by many Democrats and Republicans is that the ultimate constitutionality of DACA should have been left to the courts to resolve through the judicial process.

In his letter, Attorney General Sessions implicitly addressed this policy-oriented approach. In arguing why DACA should be rescinded immediately, he cited to the oath he took to become Attorney General. He noted that he had a duty to the constitution and to execute the laws actually passed by Congress. Essentially, his position is premised on the idea that the Attorney General has an obligation to determine the legality of a law and act accordingly. For him, it was not an issue to be left to the courts after he determined that the law was illegal. By the same logic, Attorney General Sessions could not countenance leaving the DACA policy in effect pending a legislative solution (however, he did approve the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) six-month wind-down process, although it is impossible to know if this was his preferred solution).

The positions of Jeb Bush and Attorney General Sessions highlight how different priorities and views of the roles of oath-taking government officials can lead to different resolutions despite starting from the same premise (here, that DACA was illegal). These sorts of debates come up in all sorts of issues facing our country and are well worth carefully considering.

Tying the Decision to the Fifth Circuit DAPA Injunction

In asserting that DACA was illegal, Attorney General Sessions cited to the grounds on which the Fifth Circuit based its decision to enjoin DAPA. The applicability of the DAPA injunction to DACA rests not only on the similarities between the two programs, but also on the fact that both the district court and the Fifth Circuit carefully studied the manner in which DACA had been implemented in order to adjudicate the lawsuit against DAPA. This was necessitated by the fact that DAPA had not taken effect at the time that the decisions were rendered.

The Fifth Circuit upheld the DAPA injunction on two grounds, both of which were referenced in Attorney General Sessions’ letter:

1. DAPA violated the procedural requirements of the Administrative Procedures Act (APA); and

2. The DHS lacked legal authority to implement DAPA even if it had undergone the notice and comment procedures required by the APA.

In reaching his decision, Attorney General Sessions determined that the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning applied to DACA as well.

There is one interesting point I will examine that comes not from the Sessions letter but from the DHS memorandum rescinding DACA [PDF version].

First, please refer to the “Similarities to DACA” section of my 2015 opinion blog on the Fifth Circuit decision [see blog].

As I explained, the district court looked to the implementation of DACA to determine whether the DAPA memo would afford adjudicators with genuine discretion in granting benefits. In the district court decision, Judge Andrew Hanen found that while the DACA memo instructed adjudicators to review applications on a case-by-case basis, this instruction was “merely pretext.” To this effect, he noted that only about 5-percent of the 723,000 applications that had been evaluated had been denied as of the time of his decision. Furthermore, he suggested that the instances of mandatory language in the DACA memo suggested that adjudicators were not afforded genuine discretion. This issue was important in determining whether DACA was, as the Obama Administration claimed, merely an exercise of prosecutorial discretion, or whether it was in fact an immigration benefit created without congressional authorization. The Fifth Circuit majority agreed with Judge Hanen’s analysis in upholding the injunction.

In Acting Secretary Duke’s memorandum, she stated that DACA “purported to use deferred action-an act of prosecutorial discretion meant to be applied only on an individualized case-by-case basis…” In footnote 1 of her memorandum, Secretary Duke stated that “[United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)] has not been able to identify specific denial cases where an applicant appeared to satisfy the programmatic categorical criteria as outlined in the [DACA] memorandum, but still had his or her application denied solely upon discretion.” In short, she stated that the DHS determined that provided individuals were not barred from DACA benefits, it could not identify any cases of such individuals being denied as an act of discretion. This finding appears to concede Texas’ legal arguments and that Judge Hanen was correct in his finding on this specific issue.

Conclusion

Most of the debate over DACA focuses on its policy goals. However, regardless of which side of the debate one falls, both DACA and DAPA presented interesting legal questions that will surely come up in other contexts (e.g., several of the decisions on President Trump’s so-called “travel ban” actually cited to the Fifth Circuit decision on DAPA with regard to the question of standing). These legal questions apply not only to immigration, but also to the powers of the different branches of government in general.