- Introduction: Matter of Mendez, 27 I&N 219 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 219-220

- Second Circuit Asks for Clarification from the Board: 27 I&N Dec. at 220

- Language of Federal Misprision of a Felony Statute: 27 I&N Dec. at 220 n.2

- Analytical Framework: 27 I&N Dec. at 221

- Applying the Framework to 18 U.S.C. 4: 27 I&N Dec. at 221

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Mendez, 27 I&N 219 (BIA 2018)

On February 23, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published decision in Matter of Mendez, 27 I&N Dec. 219 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. In Matter of Mendez, The Board held that misprision of a felony in violation of the Federal criminal statute 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude. In so doing, the Board reaffirmed its 2006 published decision in Matter of Robles, 24 I&N Dec. 22 (BIA 2006) [PDF version], but only outside of the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. After the Matter of Robles, decision, the respondent in that case had filed a petition for review with the Ninth Circuit. In Robles-Urrea v. Holder, 678 F.3d 702 (9th Cir. 2012) [PDF version], the Ninth Circuit granted the petition, ruling that the Board erred in interpreting the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) in holding that misprision of a felony under 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude. Thus, Matter of Mendez does not apply within the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit due to contrary Ninth Circuit precedent on the issue.

On January 5, 2017, the Board issued Amicus Invitation No. 17-01-05, soliciting briefs on whether misprision of a felony under 18 U.S.C. is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude. The central question in the amicus invitation was whether the Board should follow Robles-Urrea outside of the Ninth Circuit. In Matter of Mendez, the Board finally reached its answer, reaffirming its precedent from Matter of Robles nationwide outside of the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit. Please see our blog post to learn more about the Amicus Invitation [see blog].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 219-220

The respondent, a native and citizen of the Dominican Republic, was a lawful permanent resident of the United States. He had been admitted to the United States as a conditional permanent resident on January 28, 2004, and the conditions were removed on his permanent resident status in 2006. On December 17, 2010, the respondent was convicted in Federal court of misprision of a felony in violation of 18 U.S.C. 4. Based on that conviction, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent when he sought admission to the United States as a returning resident on March 31, 2016.

In immigration proceedings, the Immigration Judge determined that the respondent’s misprision of a felony conviction constituted a crime involving moral turpitude under section 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(I) of the INA. As a result, the Immigration Judge determined that the conviction terminated the respondent’s period of continuous residence under section 240A(d) of the INA, which rendered him statutorily ineligible for cancellation of removal.

In reaching her decision that 18 U.S.C. 4 was a crime involving moral turpitude, the Immigration Judge relied upon Matter of Robles, 24 I&N Dec. 22 (BIA 2006). The Immigration Judge noted that the Ninth Circuit had rejected Matter of Robles in Robles-Urrea v. Holder, 678 F.3d 702 (9th Cir. 2006). However, the instant cause arose in the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit rather than the Ninth Circuit. Because there was no contrary precedent to Matter of Robles from the Second Circuit, the Immigration Judge determined that she was bound to follow Matter of Robles.

The respondent appealed from the Immigration Judge’s decision to the BIA. On appeal, the respondent asked the Board to reverse its holding in Matter of Robles that 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude.

Second Circuit Asks for Clarification from the Board: 27 I&N Dec. at 220

The Board explained that its 2006 decision in Matter of Robles followed the analysis of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in Itani v. Ashcroft, 298 F.3d 1213 (11th Cir. 2002) [PDF version]. Thus, the Ninth Circuit decision in Robles-Urrea created a split between it and the Eleventh Circuit on the question of whether a conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude.

In 2015, the Second Circuit, in its decision in Lugo v. Holder, 783 F.3d 119, 120-121 (2d Cir. 2015) [PDF version), asked the Board to clarify its position on the issue of whether 18 U.S.C. 4 categorically defines a crime involving moral turpitude]. Specifically, the Second Circuit wanted the Board to state whether it would continue to follow its decision in Matter of Robles, and by effect, the analysis in Itani, or whether it would, going forward, follow the Ninth Circuit decision in Robles-Urrea. However, the Board ultimately did not resolve the issue on remand from Lugo because the case was administratively closed after the Second Circuit decision.

In 2016, the Board issued a comprehensive decision which clarified the framework for determining whether a conviction is for a crime involving moral turpitude in Matter of Silva-Trevino, 26 I&N Dec. 826 (BIA 2016) [PDF version]. Please see our article on the crime involving moral turpitude analysis in Matter of Silva-Trevino to learn more [see article].

In 2017, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit added to the circuit split on the issue in Villegas-Sarabia v. Sessions, 874 F.3d 871 (5th Cir. 2017) [PDF version], wherein it agreed with Itani and Matter of Urrea in concluding that a conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude.

As we noted in the introduction, the Board would, for reasons that we will explore in subsequent sections, affirm its 2006 determination in Matter of Robles that 18 U.S.C. 4 categorically defines a crime involving moral turpitude.

Language of Federal Misprision of a Felony Statute: 27 I&N Dec. at 220 n.2

The central question in Matter of Mendez was whether 18 U.S.C. 4 categorically defines a crime involving moral turpitude. The statute reads as follows:

Whoever, having knowledge of the actual commission of a felony cognizable by a court of the United States, conceals and does not as soon as possible make known the same to some judge or other person in civil or military authority under the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.

Analytical Framework: 27 I&N Dec. at 221

In Matter of Silva-Trevino, the Board held that the analysis of whether a conviction is a crime involving moral turpitude should be conducted within the framework of the categorical and modified categorical approaches. This means that the question of whether a conviction is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude depends on the language of the statute of conviction rather than the specific facts of the alien’s conduct. Please see our collection of articles on the categorical and modified categorical approaches to learn more about how they are used in the immigration context [see article].

The Board explained that it applies the “realistic probability test” to determine the minimum conduct that has a realistic probability of being prosecuted under a given statute, except where circuit law dictates otherwise. The Board noted that the Second Circuit applied the realistic probability test in Efstathiadis v. Holder, 752 F.3d 591, 595 (2d Cir. 2014) [PDF version].

Following this approach, the Board first looks to determine if the statute of conviction categorically defines a crime involving moral turpitude. If the statute encompasses non-turpitudious conduct that has a realistic probability of being prosecuted, the Board then looks to determine whether the statute is divisible, that is, whether it sets forth separate offenses with distinct elements. If the statute is divisible, the Board may then determine which of the alternative offenses the alien was convicted of violating.

The Board explained that the term “moral turpitude” refers to conduct that is “inherently base, vile, or depraved, and contrary to the accepted rules of morality and the duties owed between persons or to society in general.” The Board has held consistently, including in Matter of Silva-Trevino, 26 I&N Dec. at 828 n.2, held that a statute must require a culpable mental state and reprehensible conduct in order to involve moral turpitude.

Applying the Framework to 18 U.S.C. 4: 27 I&N Dec. at 221

The Board concluded that misprision of a felony under 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude under the Matter of Silva-Trevino framework. First, the Board quoted from the Second Circuit decision in United States v. Cefalu, 85 F.3d 964, 969 (2d Cir. 1996) [PDF version], which set forth the elements of misprision of a felony as follows:

1. The principal committed and completed the alleged felony;

2. The defendant had full knowledge of that fact;

3. The defendant failed to notify the authorities; and

4. The defendant took steps to conceal the crime.

Essentially, the Second Circuit in Cefalu held that each of the four above points must be proven or admitted in order to sustain a conviction for misprision of a felony.

The DHS argued that taking steps to conceal a felony is reprehensible conduct that is, in and of itself, morally turpitudinous. To this effect, the Board cited to a number of circuit court decisions holding that statutes intended to criminalize concealment of wrongdoing defined crimes involving moral turpitude. Regarding 18 U.S.C. 4 specifically, both the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits took the position that the concealment described in the misprision of a felony statute involves dishonest and deceitful behavior, which runs contrary to accepted societal duties.

The respondent and amici in support of the respondent took the position that concealment itself is not a crime involving moral turpitude unless the underlying felony is a crime involving moral turpitude. Citing to the Ninth Circuit in Robles-Urrea, 678 F.3d at 710-11, the respondent and amici argued that it would be an “absurd result” to consider an individual who conceals a felony to have committed a crime involving moral turpitude in the case where the principal felony offender did not commit a crime involving moral turpitude.

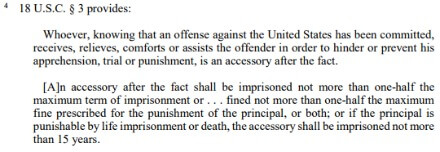

In reaching its decision in Robles-Urrea, the Ninth Circuit cited to 18 U.S.C. 3, a Federal accessory-after-the-act statute. 18 U.S.C. 3 reads as follows:

[Click image to view full size]

The Ninth Circuit had held that an alien convicted in violation of 18 U.S.C. 3 would only be considered to have been convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude if the offense by the principal offender was a crime involving moral turpitude. The Ninth Circuit extended its reading of 18 U.S.C. 3 to 18 U.S.C. 4. Interestingly, in Matter of Rivens, 25 I&N Dec. 623, 627 (BIA 2011) [PDF version], the Board had also held that a conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 3 is a crime involving moral turpitude only where the underlying offense is a crime involving moral turpitude.

However, the Board would hold in the instant case that the misprision of a felony statute in 18 U.S.C. 4 was distinguishable from the accessory-after-the-fact statute in 18 U.S.C. 3. The Board noted that a conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 3 carries a higher potential range of punishment than does 18 U.S.C. 4. Yet, the Board cited to Matter of Solon, 24 I&N Dec. 239, 240 (BIA 2007) [PDF version], in noting that “[n]either the seriousness of the underlying offense nor the severity of the punishment imposed is determinative of whether a crime involves moral turpitude.”

The Board held that the affirmative act of concealing a known felony — as set forth in 18 U.S.C. 4 — is a crime involving moral turpitude, in and of itself, regardless of the underlying conduct of the principal offender. On this point, the Board agreed with the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits. Furthermore, the Board noted that 18 U.S.C. 3 does not have as an element an act of concealment of an underlying felony. The Board added that “the range of punishment for misprision is fixed without regard to the underlying felony, while the range for accessory after the fact is directly tied to the potential punishment of the principal.”

Next, the Board addressed whether 18 U.S.C. 4 includes the requisite scienter (requirement that the offense have been committed knowingly and willfully) to categorically define a crime involving moral turpitude. The Board noted that 18 U.S.C. 4 does not include an explicit requirement that the act of concealment must be intentional. However, the Board concluded that the statute implicitly included this requirement in the language requiring a showing that the “defendant took steps to conceal the crime.” The Board cited to several circuit decisions that held that taking steps to conceal a crime under 18 U.S.C. 4 is, in and of itself, a willful act. Furthermore, the Board noted, as have multiple circuit courts, that charging documents for misprision of a felony generally specify that the act of concealment was willful. Federal jury instructions on 18 U.S.C. 4 also include the statement that the concealment must be willful. Based on the foregoing information, the Board concluded that “the concealment element of misprision requires an intentional act that is sufficiently reprehensible to be considered morally turpitudinous.” To learn more about the cases cited to by the Board, please see 27 I&N Dec. at 223-24.

The respondent further argued that the Board’s precedent from Matter of Robles conflicted with its precedent decision in Matter of Espinoza, 22 I&N Dec. 889, 892 (BIA 1999) [PDF version]. In Matter of Espionza, the Board held that misprision of a felony under 18 U.S.C. 4 was not an obstruction of justice aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the INA. In Matter of Espinoza, 22 I&N Dec. at 896, the Board reasoned that misprision of a felony “lacks the critical element of an affirmative and intentional attempt, motivated by a specific intent, to interfere with the process of justice.” However, the Board took the position that in Matter of Espionza, it “made no determination … concerning the mens rea attached to the actual act of concealment or to the question of whether the offense is a crime involving moral turpitude.” Accordingly, the Board did not agree that its holding in Matter of Robles was in conflict with Matter of Espinoza.

For the foregoing reasons, the Board dismissed the respondent’s appeal.

Conclusion

Following the Ninth Circuit decision in Robles-Urrea, there was uncertainty as to whether the Board would continue to follow its prior precedent holding that a conviction for misprision of a felony in violation of 18 U.S.C. 4 is categorically a crime involving moral turpitude. In Matter of Mendez, the Board reaffirmed its prior holding, meaning that it remains in accord with the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits. Going forward, Immigration Judges and the Board will treat a conviction for misprision of a felony under 18 U.S.C. 4 as a categorical crime involving moral turpitude in all cases arising outside the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit. Within the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit, Robles-Urrea v. Holder holds, and a conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 4 is not categorically a crime involving moral turpitude. The Ninth Circuit has jurisdiction over the following states and territories: Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

An alien who is facing criminal charges should always seek guidance on the potential immigration consequences of a conviction or plea deal. An alien in removal proceedings should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately for case-specific guidance.