On December 20, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a per curiam order [PDF version] lifting an order by the United States District Court for the Northern District of California that would have required the Trump Administration to turn over a substantial number of documents relating to its decision to terminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. The issue arises from five lawsuits filed in California against the government over the DACA termination.

As the Supreme Court explains, the plaintiffs in District Court had argue that the decision of former acting-Homeland Security Secretary Elaine Duke to rescind DACA is unlawful. Among other reasons, the plaintiffs had argued that the decision violated the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

(In an interesting aside, one of the plaintiffs in the California litigation is Janet Napolitano in her capacity as head of the President of the University of California. This is noteworthy because Napolitano originally issued the DACA memorandum when she was previously the Secretary of Homeland Security.)

In discovery, the Government had turned over 256 pages of documents relating to the decision to rescind DACA. The Government stated that those documents contained all of the non-deliberative material considered by then-acting Secretary Duke in reaching her decision to rescind DACA.

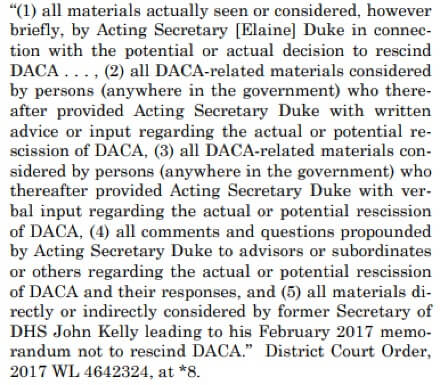

On October 17, the District Court ordered the Government to complete the administrative record by submitting more documents in accordance with the order. The Supreme Court excerpted the portion of the order that specified the documents that the Government was ordered to produce:

In response, the Government petitioned the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit for a writ of mandamus (thereby asking the Ninth Circuit to order the District Court to correct what the Government believed was its abuse of discretion in issuing the October 17 order). In In re United States, 875 F.3d 1200 (9th Cir. 2017), the Ninth Circuit denied the Government’s petition in a published opinion on November 16, 2017. On November 19, 2017, the Government filed a motion with the District Court to stay the October 17 discovery order until after the District Court ruled on a separate motion by the Government to dismiss the respondents’ motion for a temporary injunction against the DACA rescission. The District Court declined to grant the Government’s petition, but it did stay the discovery order for one month. The Government then filed a petition for a writ of mandamus with the Supreme Court.

On December 8, 2017, the Supreme Court granted the Government’s petition for a writ of mandamus and, pending further briefing, it stayed the District Court’s order to the extent that it required discovery and the production of further documents from the Government. Interestingly, the Supreme Court split on this issue, with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch voting to grant the Government’s petition (note: the opinion was un-signed, although we can assume that these five justices voted to grant the motion by the fact that the other four justices dissented). The decision drew a ten page dissenting opinion from Justice Stephen Breyer, which was joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan [PDF version].

This brings us to the Supreme Court’s December 20 decision. While the December 8 decision drew four dissents, no justices recorded dissents from the December 20 decision.

Here, the Supreme Court found that “[t]he Government makes serious arguments that at least portions of the District Court’s order are overly broad.” Based on the facts of the case, the Supreme Court held that “the District Court should have granted the respondents’ motion on November 19 to stay implementation of the challenged October 17 order and first resolved the Government’s threshold arguments…” The Court added that, were the Government to prevail on one or both of those arguments (that the decision to rescind DACA was an unreviewable exercise of discretion under 5 U.S.C. 701(a)(2) and that the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) deprives the District Court of jurisdiction), then any arguable need for the District Court to examine further documents would have been eliminated.

As a result, the Supreme Court vacated the Ninth Circuit decision denying the Government’s petition for a writ of mandamus. It then directed the Ninth Circuit to “take appropriate action so that the following steps can be taken.” The steps are as follows:

1. The District Court should rule on the Government’s threshold arguments; and

2. Thereafter, the District Court may consider whether narrower amendments to the record via additional discovery are necessary and appropriate.

As we noted, if the District Court agrees with one or both of the Government’s threshold arguments, then the issue of whether further documents are necessary may be mooted. Neither of the Government’s threshold arguments has to do with why DACA was rescinded, but rather whether the decision is reviewable on the grounds claimed by the plaintiffs. The second point is interesting as well. Assuming that the District Court rejects the Government’s threshold arguments, then the Supreme Court’s decision does not preclude the possibility that it may direct the Government to produce additional documents. However, the Court stated that it may consider, in that case, “narrower amendments to the record,” thus seeming to confirm that the Court agrees with the Government’s position that the District Court discovery order was over-broad even when considered separately from the issue of the Government’s threshold arguments. However, we must also note that the Court added that “[t]his order does not suggest any view on the merits of the respondents’ claims or the Government’s defenses…”

Finally, the Supreme Court precluded the District Court from “compel[ling] the Government to disclose any document that the Government believes is privileged without first providing the Government with the opportunity to argue the issue.”

Although we have not yet covered the challenges to the DACA rescission in California and, separately, e in Federal District Court in Brooklyn, we will update the site with any major developments in the cases. Furthermore, we will update the site on any news from Congress regarding a potential legislative replacement.

Despite the pending litigation and debate in Congress, it is safest for those affected by the potential rescission of DACA to proceed as if DACA will be rescinded and plan accordingly. Those with specific questions should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance.

Please see our full article to learn about the DACA rescission and related issues in detail [see article].