- Introduction: Pereira v. Sessions, 138 S.Ct. 2105 (2018)

- Opinion of the Court

- Part I-A and B: Statutory, Regulatory, and Administrative Background of Relevant provisions

- Part I-C: Factual and Procedural History

- Part II-A: Issues Before the Court and Determination that Chevron Deference Does Not Apply

- Part II-B: Statutory Text Resolves the Issue Without Resorting to Chevron

- Part III-A thru III-E: Majority Rejects Government’s and Dissent’s Arguments

- Part IV: Conclusion

- Decisions Abrogated by Pereira

- Concurring Opinion: Justice Anthony Kennedy Questions Current Application of Chevron Doctrine

- Dissenting Opinion: Justice Alito Would Have Held that Government Was Entitled to Deference

- Conclusion

Introduction: Pereira v. Sessions, 138 S.Ct. 2105 (2018)

On June 21, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States issued its decision in Pereira v. Sessions, 138 S.Ct. 2105 (2018) [PDF version]. In Pereira, the Court held that a putative “notice to appear” that does not designate a specific time or place of removal proceedings is not a “notice to appear” as defined in section 239(a)(1) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). As a result, the court held that a putative notice to appear that does not designate a specific time or place of removal proceedings does not trigger the stop-time rule ending a noncitizen’s period of continuous physical presence in the United States, and which in turn affects eligibility for cancellation of removal under the INA.

The Court’s decision reversed a contrary decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in Pereira v. Sessions, 866 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2017) [PDF version].

The decision was written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor and joined by seven of her colleagues. A concurring opinion addressing issues involving administrative deference was authored by now-former Justice Anthony Kennedy. Justice Samuel Alito filed a solo-dissenting opinion.

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of Pereira, the Court’s analysis and conclusions, and what this important new precedent means going forward. We will also examine in brief the concurring and dissenting opinions. Please see our article index on this decision and related decisions and issues to learn more about what constitutes a proper notice to appear in various contexts [see index]. Our index includes an article on the subsequent Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) decision in Matter of Bermudez-Cota, 27 I&N Dec. 441 (BIA 2018) [PDF version], wherein the Board distinguished Pereira in holding that a notice to appear that does not specify the time and place of an alien’s initial removal hearing but that is followed by a notice of hearing specifying this information at a later date vests an immigration judge with jurisdiction over the removal proceedings [see article].

Opinion of the Court

The opinion of the Court was authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. She was joined in full by Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Elena Kagan, and Neil Gorsuch. The opinion of the Court constitutes binding precedent throughout the United States going forward. In the following subsections, we will examine the opinion of the Court in full, section by section.

Part I-A and B: Statutory, Regulatory, and Administrative Background of Relevant provisions

Section 240A(b) of the INA allows the Attorney General to cancel the removal and adjust the status of qualified non-permanent residents in section 240 removal proceedings. In order to be eligible for non-permanent resident cancellation of removal (“cancellation-b”), the alien must meet several statutory requirements. The pertinent requirement at issue in the instant case, found in section 240A(d)(1)(A), is that the alien must have “been physically present in the United States for a continuous period of not less than 10 years immediately preceding the date of [an] application for cancellation of removal.” Under the same provision, the accrual of “continuous physical presence” ceases “when the alien is issued a notice to appear under [section 239(a) of the INA].” This latter point is referred to as the “stop-time rule.”

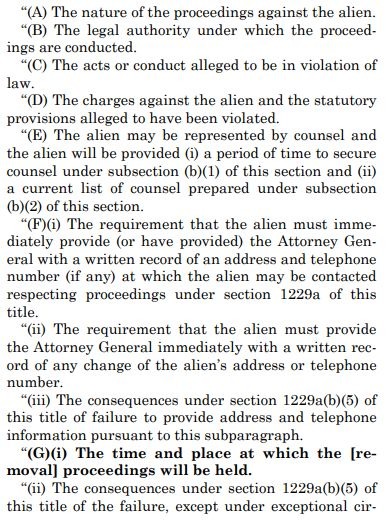

Section 239(a) defines a “notice to appear” as “specifying” the following:

As you can see, the opinion highlighted section 239(a)(1)(G)(i) for emphasis. This provision states that the notice to appear specifies “[t]he time and place at which the [removal] proceedings will be held.” Interpreting this provision was one of the central aspects of the case, as we will see going forward in the article.

Section 239(a)(2)(A) gives the Government the ability to change or postpone the time or place of removal proceedings. In order to change the time or place of removal proceedings, the Government must provide the alien with “a written notice … specifying … the new time or place of the proceedings…” as well as the consequences for failure to appear. The Government is not required to provide written notice of a change to the time or place of removal proceedings if the alien is (1) not in detention and (2) has failed to provide his or her address to the Government.

Justice Sotomayor explained that an alien may face severe consequences for a failure to appear at proceedings after having been provided with written notice. Absent “exceptional circumstances,” an alien “shall be ordered removed in absentia” after failing to appear if the Government establishes by “clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence” that notice was provided and that the alien is removable (section 240(b)(5)(A)). , Under section 240(b)(7), provided that he or she “was provided oral notice … of the time and place of the proceedings and the consequences” of failure to appear, an alien ordered removed in absentia is ineligible for certain forms of relief Under section 240(b)(5)(C), an in absentia removal order may be rescinded if the alien “demonstrates that [he or she] did not receive notice in accordance with [section 240(a)(1) or (a)(2)].

The statute setting forth the notice to appear provisions was part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA), 110 Stat. 3009-546. Shortly after IIRIRA was passed, the Attorney General promulgated regulations for its implementation. At 62 FR 10332 (1997), the Attorney General promulgated regulations stating that the notice to appear only needs to provide the time and date of the initial removal proceeding “when practicable.” As a result, the vast majority of notices to appear have since omitted the time and date of the proceeding, instead listing those details as “to be determined.”

The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) addressed the issue of what constitutes a valid notice to appear for purposes of triggering the stop-time rule in its published decision, Matter of Camarillo, 25 I&N Dec. 644 (BIA 2011) [PDF version]. In Matter of Camarillo, the Board held that a notice to appear that does not specify the time and place of an initial proceeding is nevertheless sufficient for triggering the stop-time rule. The Board reasoned that the language of the stop-time rule only specifies the type of document that the DHS must serve on the alien, but includes no other substantive requirements regarding the information that must be included in the document.

Part I-C: Factual and Procedural History

The petitioner, Wescley Fonseca Pereira, was a native and citizen of Brazil. He was admitted to the United States as a non-immigrant visitor in 2000. He remained in the United States after his nonimmigrant visa expired.

In 2006, Pereira was arrested in Massachusetts for operating a vehicle under the influence of alcohol. On May 31, 2006, he was served by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) with a notice to appear. The putative notice charged Pereira with removability based on his having overstayed his nonimmigrant visa. The notice informed Pereira that the DHS was initiating removal proceedings against him, and provided him with further information about the “[c]onduct of the hearing” and the consequences for failing appear. However, it did not specify the date and time of the initial hearing, instead instructing him to appear before an Immigration Judge in Boston “on a date to be set at a time to be set.”

On August 9, 2007, the DHS filed the notice to appear with the Boston Immigration Court. The Immigration Court attempted to mail Pereira a notice setting the time and date that his initial removal hearing was to be held on October 31, 2007. However, this notice was returned as undeliverable because the Immigration Court had used Pereira’s street address rather than the post office box he had provided to DHS. Pereira failed to appear having not received the notice due to Government error, and he was ordered removed in absentia. He remained in the United States unaware of the fact that he had been ordered removed.

In 2013, after Pereira had accrued more than 10 years of presence in the United States, he was arrested for a minor vehicle violation. Subsequent to his arrest, he was detained by the DHS. The Immigration Court reopened removal proceedings against Pereira after he established that he had not received the Immigration Court’s 2007 notice specifying the date and time of his initial hearing. In the reopened proceedings, Pereira applied for cancellation of removal. Although the issuance of a notice to appear stops the accrual of continuous physical presence, and although Pereira’s was issued within 10-years of his entry, Pereira argued that the notice to appear issued to him in 2006 did not trigger the stop-time rule because it did not include information about the time and date of his initial removal hearing.

The Immigration Judge disagreed with Pereira’s argument, referring to the BIA decision in Matter of Camarillo in stating that the law was “quite settled that DHS need not put a date certain on the Notice to Appear in order to make that document effective.” (Internal citation omitted.) The Immigration Judge thus concluded that Pereira could not meet the 10-year continuous physical presence requirement, barring him from eligibility for cancellation of removal. The BIA dismissed Pereira’s appeal, declining to revisit its precedent from Matter of Camarillo.

Pereira appealed from that decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. In Pereira v. Sessions, 866 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2017), the First Circuit dismissed Pereira’s appeal. The First Circuit deferred to the BIA’s interpretation of the pertinent statutes, following the Supreme Court decision in Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984) [PDF version], which requires courts to defer to an administrative agency’s interpretation of a statute if (1) the statute is ambiguous and (2) the agency’s interpretation is reasonable. The First Circuit first concluded that the statutes were ambiguous and second concluded that the Board’s interpretation was reasonable. We discuss the First Circuit decision in more detail in our article on the Supreme Court’s decision to grant certiorari (agreed to hear the case) in Pereira [see section].

Part II-A: Issues Before the Court and Determination that Chevron Deference Does Not Apply

Justice Sotomayor began by explaining that the Court granted certiorari to resolve a split between the Federal circuit courts. While the First Circuit had deferred to the BIA’s interpretation of the relevant statutes, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit had concluded that the statute was not ambiguous and that the Board’s position on the issue was not entitled to deference [see section]. However, several other circuits, including the United States Courts of Appeals for the Second, Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh Circuits had issued published decisions reaching the same result as the First Circuit. Please see our section later in the article to learn about which decisions were abrogated by the Supreme Court’s decision in Pereira [see section].

The Supreme Court considered the following question on review: “Does service of a document styled as a ‘notice to appear’ that fails to specify ‘the items listed’ in [INA section 239(a)(1)] trigger the stop time rule?” [see section].

The Court began by noting that the question presented by Pereira — whether the notice must include all the items listed in section 239(a)(1) — was broader than what was necessary to resolve the instant case. Accordingly, Justice Sotomayor, writing for the Court, wrote that “the dispositive question in this case is much narrower, but no less vital: Does a ‘notice to appear’ that does not specify the ‘time and place at which the proceedings will be held,’ as required by [section 239(a)(1)(G)(i)], trigger the stop-time rule?” In footnote five to the decision, the majority opted to leave for another day whether a putative notice to appear that omits any of the other categories listed in section 239(a)(1) suffices for triggering the stop-time rule. Thus, the decision should not be read as creating any binding precedent on any provision of section 239(a) with regard to the stop-time rule other than the time and place of hearings requirement.

Significantly, the Supreme Court began by parting from the First Circuit and several of its sister circuits, concluding that “the Court need not resort to Chevron deference…, for Congress has supplied a clear and unambiguous answer to the interpretive question at hand.” The answer to whether a ‘notice to appear’ that does not specify the ‘time and place at which the proceedings will be held,’ as required by [section 239(a)(1)(G)(i)], trigger the stop-time rule,”, Justice Sotomayor wrote, was that “[a] putative notice to appear that fails to designate the specific time or place of the noncitizen’s removal proceedings is not a ‘notice to appear under section 239(a),’ and so does not trigger the stop-time rule.”

Part II-B: Statutory Text Resolves the Issue Without Resorting to Chevron

Justice Sotomayor began this part of the Court’s opinion by stating that “[t]he statutory text alone is enough to resolve this case.” She quoted from the stop-time rule at section 240A(d)(1): “any period of … continuous physical presence” is “deemed to end … when the alien is served a notice to appear under [INA section 239(a)].” She wrote that the language of section 240A(d)(1) “specifies where to look to find out what ‘notice to appear’ means,” here being section 239(a). Section 239(a) defines the “notice to appear.” Among the content that it describes a notice to appear “specifying” is found in section 239(a)(1)(G)(i): “The time and place at which the [removal] proceedings will be held.” From this reading of the statute, the majority held that “it is clear that to trigger the stop-time rule, the Government must serve a notice to appear that, at the very least, ‘specif[ies]’ the ‘time and place’ of removal proceedings.”

The Government, as well as Justice Alito in dissent, found it significant that the stop-time rule does not reference any single provision of section 239(a), but rather section 239(a) generally, which includes paragraph (1), (2), and (3). However, the majority found this to be insignificant, noting that the Government itself conceded that “only paragraph (1) bears on the meaning of a ‘notice to appear.” Paragraph (2) discusses “[n]otice of a change in time or place of proceedings” and paragraph (3) sets forth a system to record noncitizens’ addresses and phone numbers. Justice Sotomayor wrote that “the term ‘notice to appear’ appears only in paragraph (1),” and that paragraph 1 is the only part of section 239(a) which “purport[s] to delineate the requirements of a “notice to appear.”

Justice Sotomayor wrote that section 239(a)(2) strengthens, rather than weakens, the assertion that a notice to appear must include the time and place of proceedings. Under the provision, in order for the Government to change or postpone the time and place of removal proceedings, it is required to provide an alien with “written notice … specifying … the new time or place of proceedings.” The majority took the position that the language of section 239(a)(2) “presumes that the Government has already served a ‘notice to appear under section [239(a)]’ that specified the time and place as required by [section 239(a)(1)(G)(i).” She added that this point was conceded by Justice Alito in his dissent, although he, unlike the majority, considered it to be “entirely irrelevant.” Writing for the majority, however, Justice Sotomayor wrote that “[p]aragraph (2) clearly reinforces the conclusion that ‘a notice to appear under section 239(a),’ [section 240A(d)(1)], must include at least the time and place of the removal proceedings to trigger the stop-time rule.”

The majority also found support for its reading of the statutes in section 239(b)(1), which provides an alien with “the opportunity to secure counsel before the first [removal] hearing date,” and also providing that the “hearing date shall not be scheduled earlier than 10 days after the service of the notice to appear.” The majority reasoned that in order for section 239(b)(1) “to have any meeting, the ‘notice to appear’ must specify the time and place that the noncitizen, and his counsel, must appear at the removal hearing.” Were this not the case, Justice Sotomayor wrote that “the Government could serve a document labeled ‘notice to appear’ without listing the time and location of the hearing and then, years down the line, provide that information a day before the removal hearing when it becomes available,” thus depriving the alien of a meaningful “opportunity to secure counsel.”

Finally, the majority discussed the appearance of the term “notice to appear” in the stop-time rule statute. Here, the Court wrote that “[c]onveying … time-and-place information to a noncitizen is an essential function of a notice to appear, for without it, the Government cannot reasonably expect the noncitizen to appear for removal proceedings.” A contrary holding, Justice Sotomayor wrote, “would empower the Government to trigger the stop-time rule merely by sending noncitizens a barebones document listed ‘Notice to Appear,’ with no mention of the time and place of removal proceedings, even though such documents would do little if anything to facilitate appearance at those proceedings.”

Part III-A thru III-E: Majority Rejects Government’s and Dissent’s Arguments

Having explained its reasoning, the majority moved to discuss the Government’s and the dissent’s arguments in favor of their position on what constitutes a “notice to appear” for purpose of triggering the “stop time rule.” We will examine these arguments in brief and the majority’s reasons for rejecting them below. Please note that you can read more about the Government’s arguments in our post on the oral arguments in Pereira [see blog].

The Government’s first argument was that section 239(a) is not definitional, and for that reason, “cannot circumscribe what type of notice counts as a ‘notice to appear.’” However, the majority concluded that section 239(a)(1)’s providing that the notice it describes is “referred to as a ‘notice to appear’” is “quintessential definitional language.” Furthermore, section 239(a)(1)(G)(i) specifies the time-and-place requirement as being part of a notice to appear. The majority concluded that other uses of the term “notice to appear” “carr[y] with [them] the substantive time-and-place criteria required by [section 239(a)].” In dissent, Justice Alito argued that section 239(a)(1) is not a “definition” of a notice to appear, but rather “can be understood to define what makes a notice to appear complete.” However, the majority read the provision differently, holding that section 239(a)(1)(G) makes the time-and-place requirement an intrinsic part of the notice to appear, meaning that a notice that lacks the time-and-place requirement is not merely an incomplete notice to appear, but rather is not a notice to appear at all.

The Government then argued that the use of the word “under” in the stop-time rule (“under section [239(a)]”) was ambiguous. Specifically, the Government argued that “the word ‘under’ in that provision means ‘subject to,’ ‘governed by,’ or ‘issued under the authority of.’” (Majority’s paraphrase of the Government’s position.) In dissent, Justice Alito argued that “under” can mean “authorized by.” Both the Government and Justice Alito further argued that the word “under” as used in section 239(a) can be read as applying the stop-time rule as long as the DHS “serves a notice that is ‘authorized by,’ or ‘subject to or governed by, or issued under the authority of’ [section 239(a)]…” However, the majority rejected this reading of the stop-time rule, stating that “we think it obvious that the word ‘under,’ as used in the stop-time rule, can only mean ‘in accordance with’ or ‘according to,’ for it connects the stop-time trigger in [section 240A(d)(1)] to a ‘notice to appear’ that contains the enumerated time-and-place information described in [section 239(a)(1)(G)(i)].” That is, the majority read the statute as only applying the stop-time rule “if the Government serves a ‘notice to appear’ ‘[i]n accordance with’ or ‘according to’ the substantive time-and-place requirements set forth in [section 239(a)].”

The Government’s final statutory text-based arguments relied on comparing the language of the stop-time rule to similar INA provisions. First, the Government noted that two provisions relating to in absentia removal orders (section 240(b)(5)(A) and 240(b)(5)(C)(ii)) state, respectively, that an alien may be ordered removed in absentia if he or she was provided with the “required” written notice, and that an alien may seek to reopen proceedings after being ordered in absentia if he or she establishes that he or she was not provided with the notice “in accordance” with two provisions requiring it. The Government found the use of the terms “required” and “in accordance” significant in comparison to the stop-time rule, which merely uses “under.” However, the majority concluded that the Government did not offer a convincing argument for why the difference in terms necessitated the conclusion that the use of the term “under” in the stop-time rule entailed a lesser notice requirement than the language employed in the in absentia removal order provisions. It stated that “[t]he far simpler explanation, and the one that comports with the actual statutory language and context, is that each of these three phrases refers to notice satisfying, at a minimum, the time-and-place criteria defined in [section 239(a)(1)]. The majority was also not persuaded by the Government’s invocation of section 240(b)(7), which renders an alien ordered removed in absentia ineligible for certain forms of discretionary relief for a period of 10 years, provided that he or she “was provided oral notice … of the time and place of the proceedings” at the time the notice was issued. Here, the Government argued that the explicit reference to “the time and place of the proceedings” distinguished this provision from the stop-time rule. However, the majority was not persuaded that the lack of this specific language in the stop-time rule changed the fact that the stop-time rule requires a “notice to appear,” and that the notice must include the time and place of the proceedings.

The Government took the position that the “administrative realities of removal proceedings” make it difficult, if not impractical, to guarantee a specific time, date, and place for removal proceedings. However, the majority found this argument to be unavailing, noting that section 239(a)(2) allows the Government to change the time, date, and place of proceedings with written notice. In dissent, Justice Alito argued that the majority’s position would encourage the Government to provide “arbitrary dates and times that are likely to confound all who receive them.” Here, the majority rejected the presumption that the Government is “utterly incapable of specifying an accurate date and time on a notice to appear and will instead engage in ‘arbitrary’ behavior.”

Finally, the Government argued that the purpose and legislative history of the stop-time rule made it clear that its primary purpose is to prevent aliens in removal proceedings from delaying proceedings merely to “buy time” during which they can accrue continuous physical presence to meet the requirement for cancellation of removal. However, the Court held that requiring that the notice to appear include time-and-place information to trigger the stop-time rule is not inconsistent with its purpose.

In conclusion, the majority stated that it opted to “apply the statute as it is written” (internal citation omitted) in light of its plain language.

Part IV: Conclusion

The Supreme Court reversed the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Decisions Abrogated by Pereira

Because the Supreme Court reversed the First Circuit on appeal, the First Circuit’s decision is no longer good law. However, the decisions of the Supreme Court on an issue are binding nationwide, not just in the single case it resolves on appeal. As we noted earlier, several circuits had reached the same conclusion as the First Circuit that a notice to appear need not include the time and place of proceedings to trigger the stop-time rule. In the syllabus of the Supreme Court’s opinion, it listed decisions that are abrogated by the Court’s decision in Pereira.

First, the following are circuit court precedent decisions (meaning those binding throughout their jurisdictions) that were abrogated by Pereira:

Moscoso-Castellanos v. Lynch, 803 F.3d 1079 (9th Cir. 2015) [PDF version]

Guaman-Yuqui v. Lynch, 786 F.3d 235 (2d Cir. 2015) [PDF version]

Gonzalez-Garcia v. Holder, 770 F.3d 431 (6th Cir. 2014) [PDF version]

Yi Di Wang v. Holder, 759 F.3d 670 (7th Cir. 2014) [PDF version]

Urbina v. Holder, 745 F.3d 736 (4th Cir. 2014) [PDF version]

In addition, the Supreme Court also noted that the unpublished decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in O’Garro v. U.S. Atty. Gen, 805 Fed.Appx. 951 (Mem), was also abrogated. Unpublished decisions are non-binding on other cases but may still be referred to as guidance.

Finally, the Board’s published decision in Matter of Camarillo was effectively overruled. Board decisions are binding on immigration judges. In general, immigration judges had been applying Matter of Camarillo outside of the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, which, as we noted, had not defered to the Board’s precedent.

To learn about the jurisdictions covered by the various circuits, please see our full article on the subject [see article].

Concurring Opinion: Justice Anthony Kennedy Questions Current Application of Chevron Doctrine

The now-former [see blog] Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote an interesting concurring opinion about the state of the current Chevron doctrine.

Justice Kennedy agreed that Chevron did not apply in the instant case because the statute was unambiguous.

He noted that various Federal courts of appeals had initially assumed in their consideration of the issue that a notice to appear must be “perfected,” that is, must include the time and place of proceedings in order to trigger the time rule. He listed the following decisions:

Guamanrrigra v. Holder, 670 F.3d 404, 410 (2d Cir. 2012) [PDF version]

Dababneh v. Gonzales, 471 F.3d 806, 809 (7th Cir. 2006) [PDF version]

Garcia-Ramirez v. Gonzales, 423 F.3d 935, 937, n.3 (9th Cir. 2005) [PDF version]

However, Justice Kennedy stated that this “emerging consensus abruptly dissolved not long after the [BIA] reached a contrary interpretation of [section 240A(d)(1), or the “stop-time rule”] in Matter of Camarillo…” After Matter of Camarillo, “at least six Courts of Appeals [in addition to the First Circuit], citing Chevron, concluded that [section 240A(d)(1)] was ambiguous and then held that the BIA’s interpretation was reasonable.”

Justice Kennedy was concerned with the fact that, in his view, “some Courts of Appeals engaged in cursory analysis of the questions whether, applying the ordinary tools of statutory construction, Congress’ intent could be discerned … and whether the BIA’s interpretation was reasonable…” (Internal citations omitted.) For example, Justice Kennedy quoted from the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Urbina. There, after agreeing with the Board that the statute was ambiguous without elaborating on why, the Fourth Circuit concluded that the Board’s interpretation of the statute was reasonable “for the reasons the BIA gave in that case.” Justice Kennedy described this cursory analysis in Urbina as suggesting “an abdication of the Judiciary’s proper role in interpreting federal statutes.”

Justice Kennedy stated that the “reflexive deference” of several circuits in some of the aforementioned cases was “troubling.” He added that it is even more troubling when that type of reflexive deference is extended to other cases involving “an agency’s interpretation of the statutory provisions that concern the scope of its own authority…” He cited to the following concurring and dissenting opinions for articulating these concerns:

Arlington v FCC, 569 U.S. 290, 327 (2013) (ROBERTS, C.J., dissenting) [PDF version]

Michigan v. EPA, 135 S.Ct. 2699, 2712-2714 (THOMAS, J., concurring) [PDF version]

Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 1142, 1149-58 (10th Cir. 2016) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) [PDF version] and [see blog]

In light of these trends, Justice Kennedy wrote that “it seems necessary and appropriate to reconsider, in an appropriate case, the premises that underlie Chevron and how courts have implemented that decision. The proper rules for interpreting statutes and determining agency jurisdiction and substantive agency powers should accord with constitutional separation-of-powers principles and the function and province of the judiciary.”

In short, Justice Kennedy took the view that many circuit courts were improperly deferential to the BIA’s reading of the stop-time rule statute and neglected the normal tools of statutory analysis. He suggested that these cases were reflective of a trend where circuit courts have misapplied Chevron in deferring to certain agency actions. In light of this, he stated that the Court should consider the issue in an appropriate case. Of course, since Justice Kennedy has retired, it will be up to the remaining justices and his replacement to determine whether they want to consider the issue. While several justices, notably Justice Thomas and Justice Gorusch, have expressed skepticism about the Chevron doctrine, no other Justices signed on to Justice Kennedy’s concurring opinion.

Dissenting Opinion: Justice Alito Would Have Held that Government Was Entitled to Deference

Justice Samuel Alito was the lone Justice to dissent from the Court’s opinion in Pereira. Unlike the majority, he would have ruled that the language of the “stop-time rule” and the notice to appear provision are ambiguous and that the BIA’s interpretation of the relevant provisions was reasonable and thus entitled to deference under Chevron. Although the lopsided margin of the Court in Pereira strongly suggests that Justice Alito’s position will not prevail in the near future, his opinion is still well worth examining in brief to explore some of the tensions surrounding the current application of the Chevron doctrine.

Justice Alito described the dispute between Pereira and the Government as “a quasi-metaphysical disagreement about the meaning of the concept of a notice to appear.” The question in the instant case was whether the requirements of section 239(a)(1) are essential to the concept of a notice to appear (meaning that a notice lacking any of these points would not be a “notice to appear” at all), or whether they are things that should be on a notice to appear but that are not essential to the concept of the notice to appear. Unlike the majority, Justice Alito did not believe that the statutory language necessitated one of these readings of section 239(a)(1), both of which he deemed to be plausible. While noting that choosing between them “might have been a challenge in the first instance,” he stated that no such challenge was before the Court, since the BIA had already chosen a plausible interpretation. He added, citing to INS v. Aguirre-Aguirre, 526 U.S. 415, 425 (1999) [PDF version], that “deference to the Government’s interpretation ‘is especially appropriate in the immigration context’ because of the potential foreign-policy implications.”

Justice Alito then interpreted the “when the alien is served a notice to appear under section [239(a)]…” (emphasis added) language of the stop-time rule at section 240A(d)(1). Unlike the majority, Justice Alito found the word “under” to be ambiguous, and concluded that the Government’s argument that it meant “authorized by” or something analogous to be reasonable, citing to similar uses of under in other statutes. In short, Justice Alito summarized his view by stating that “[o]n that reasonable reading, the phrase ‘under section [239(a)]’ acts as shorthand for a type of document governed by [section 239(a)].” (Emphasis added.) As the majority noted, Justice Alito found it significant that section 240A(d)(1) does not incorporate specific language stating that all of the points listed in section 239(a)(1) must feature in order for a notice to trigger the stop-time rule.

Next, Justice Alito discussed an argument of the Government that was addressed often in oral arguments [see blog] but then not noted by the majority in the Opinion of the Court. Here, he explained that when Congress enacted the stop-time rule in 1996, it explicitly applied it “to notices to appear issued before, on, or after the date of the enactment of this act.” IIRIA, sec. 309(c)(5), 110 Stat. 3009-627. However, there had been no notices to appear issued prior to the Act because the pertinent document had been the order to show cause. To ameliorate this problem, Congress subsequently clarified that the stop-time rule should also apply “to orders to show cause, issued before, on, or after the date.” Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act, sec. 203(1), 111 Stat. 2196, as amended 8 U.S.C. 1101 note. Justice Alito found this significant because orders to show cause were not required to include the date or location of proceedings under prior statutes. He stated that this amendment “demonstrates that when it comes to triggering the stop-time rule, Congress attached no particular significance to the presence (or absence) of information about the date and time of a removal proceeding.” He added that “Congress clearly thought of orders to show cause as the functional equivalent of notices to appear for purposes of the stop-time rule,” and that in doing so Congress was “referring to a category of documents that do not necessarily provide the date and time of a future removal proceeding.”

Justice Alito stated that Pereira’s preferred reading of the statutes, as well as that of the majority, “clash with any conceivable statutory purpose.” Here, he accepted the Government’s argument that it cannot provide accurate times and dates for proceedings far in advance, and that while notices to appear are issued by DHS, removal proceedings are within the province of the Department of Justice (DOJ). He added that in light of the implausibility of providing accurate estimated dates, the provisions allowing for a change in the date provide little relief, as they are “likely to mislead many recipients and to prejudice those who make preparations on the assumption that the initial date is firm.” We discussed the majority’s responses to these arguments in our sections on the Opinion of the Court.

Justice Alito granted that the majority’s opinion, as well as Pereira’s position, “may be [a] reasonable” interpretation of the statutes. However, he stated that “the Court goes much too far in saying that it is the only reasonable construction.” Indeed, Justice Alito would have ruled that “the Government’s interpretation can be easily squared with the text of [section 239(a)(1)].” Specifically, Justice Alito disputed that the language of section 239(a)(1) necessitates the result that a notice lacking any of the ten requirements, and specifically the time-and-place requirement, is not a notice to appear. He instead concluded that section 239(a)(1) can reasonably be read as a list of things that would appear on a “complete” notice to appear. He explained, using an analogy, that a car with three wheels is still a car, just a car lacking a wheel. Discussing the Federal rules of civil procedure, Justice Alito explained that notices of appeals are still deemed to be notices of appeal even if they are deficient in some manner. He summarized his point by stating that “just because a legal document is incomplete, it does not necessarily follow that it is without legal effect.” For this reason, he did not find it unreasonable to conclude that an imperfect notice is still a notice to appear under section 239(a) for purpose of triggering the stop-time-rule.

Justice Alito was similarly unpersuaded by the majority’s relying on section 239(a)(2)(A)(i) to support its reading of section 239(a)(1). Section 239(a)(2)(A)(i) allows for the “change or postponement” of removal proceedings to a “new time or place.” The majority stated that this presupposed that a notice to appear including the time and place of proceedings had already been issued. Justice Alito agreed, but he wrote that he considered this “entirely irrelevant” to the proper reading of section 239(a), and specifically 239(a)(1)(G)(i). He reasoned that this point was not relevant to the question of whether an incomplete notice triggers the stop-time rule, and suggested that the majority was “reasoning backwards from its conclusion.” Justice Alito was also not persuaded by the majority’s references to section 240(b)(1), which, in most cases, prevents the Government from scheduling a hearing date earlier than 10 days after the service of a notice to appear. Regarding the majority’s claim that the Government’s reading of the statute would allow it to issue a notice to appear without the time and date of proceedings and then schedule a hearing years down the line with less than 10 days’ notice, Justice Alito stated that this was a “remote and speculative possibility depend[ing] entirely on the Immigration Court’s allowing a removal proceeding to go forward only one day after an alien (and the Government) receives word of a hearing date.” He noted that in such a hypothetical scenario, the Immigration Court’s decision would be subject to appeal.

Finally, Justice Alito stated that the majority overstated how much its statutory construction was based on “common sense,” noting that seven Federal circuit courts deferred to the Government’s construction of the statute whereas only one did not afford deference. He suggested that the majority’s confidence in its “common sense” reading depended on its position that “notices to appear serve primarily as a vehicle for communicating to aliens when and where they should appear for removal hearings.” While granting that this was a “reasonable interpretation with some intuitive force behind it…” he asserted that it was “not the only possible understanding or necessarily the best one.” Notably, he also found plausible the Government’s position that the notice to appear “can … be understood to serve primarily as a charging document.”

Justice Alito predicted that adverse consequences would result from the decision, including, as the majority referenced, the Government being forced to issue notices to appear with arbitrary times and dates in order to trigger the stop-time rule. He stated that “[a]t most, we can hope that the Government develops a system in the coming years that allows it to determine likely dates and times before it sends out initial notices to appear.”

In conclusion, Justice Alito addressed Justice Kennedy’s concurrence and what he saw as other opinions from members of the Court calling into question Chevron. He stated that “unless the Court has overruled Chevron in a secret decision that has somehow escaped my attention, it remains good law.”

Conclusion

The Board’s decision in Pereira is highly consequential. As an immediate matter, the Board’s decision means that a notice to appear without the time or date of proceedings does not trigger the stop-time rule going forward. This will generally require the Government to issue notices to appear with an estimated time and date for the initial proceedings.

However, there are still many unanswered questions about the breadth of the decision beyond the instant case or how it may apply to instant cases. Notably, the Board subsequently held in Matter of Bermudez-Cota that a notice to appear that lacks the time and date nevertheless vests an Immigration Judge with jurisdiction over removal proceedings, provided that the notice of the hearing is later sent to the alien [see article]. In Bermudez-Cota, the Board distinguished Pereira, which addressed specifically deficient notices in the context of the stop-time rule, but not when jurisdiction vests in the Immigration Judge. See also Ramat v. Nielsen, 317 F.Supp.3d 1111 (S.D. Cal. 2018).

It is likely that issues stemming from Pereira, including the open question of whether all parts of section 239(a)(1) are intrinsic to the “notice to appear,” will be further litigated in the coming months and years. We will continue to update the site with more information as it becomes available.

Those with case-specific questions regarding a notice to appear, eligibility for relief from removal, or removal proceedings in general should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately. To learn more about these issues, please see our growing selection of articles in our Removal and Deportation Defense section [see category].