- Introduction

- Summarizing Previous Policy

- USCIS’s Reasons For Change in Policy

- New Policy

- Note on 2004 Aytes Memo

- Conclusion

Introduction

On October 23, 2017, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) released Policy Memorandum 602-0151, titled “Rescission of Guidance Regarding Deference to Prior Determinations of Eligibility in the Adjudication of Petitions for Extension of Nonimmigrant Status.” This new memorandum instructs USCIS officers to apply the same level of scrutiny to requests for extension of status in certain nonimmigrant visa categories that it applies to the initial requests for the visas. In so doing, the new Memorandum rescinds an April 23, 2004 memorandum titled “The Significance of a Prior CIS Approval of a Nonimmigrant Petition in the Context of a Subsequent Determination Regarding Eligibility for Extension of Petition Validity.”

In this article, we will examine the new guidance for certain nonimmigrant visa extension petitions and compare them to the guidance that had been in effect since 2004. We have uploaded the memoranda that we will be discussing in this article below:

PM-602-0151: “Rescission of Guidance Regarding Deference to Prior Determinations of Eligibility in the Adjudication of Petitions for Extension of Nonimmigrant Status” (Oct. 23, 2017) [PDF version];

PM-602-0111: “L-1B Adjudications Policy” (Aug. 17, 2015) [PDF version] [see article]; and

Memo, Yates, Associate Director for Operations, HQOPRD 72/11.3, “The Significance of a Prior CIS Approval of a Nonimmigrant Petition in the Context of a Subsequent Determination Regarding Eligibility for Extension of Petition Validity” [PDF version].

In the article, we will refer to the three above memoranda as the “2017 Memo,” “2015 L1B Memo,” and “2004 Yates Memo” respectively.

The new policy comes as a result of President Donald Trump’s “Buy American, Hire American” Executive Order. To learn more about the Executive Order’s implications for immigration policy, please see our full article on the subject [see article]. Please also see our website’s section on work visas to learn more about specific categories that are affected [see category], including commonly used categories such as H1B [see category], L1 [see category], O [see category], and P.

Summarizing Previous Policy

The 2017 Memo begins by summarizing the 2004 Aytes Memo.

The 2004 Aytes Memo provided guidance to USCIS adjudicators when considering certain nonimmigrant visa extension petitions. Where the extension petition involved the same parties and same underlying facts as the initial petition for the visa, it instructed adjudicators to, in most cases, defer to prior determination of eligibility for the visa. The 2017 Memo included an excerpted portion of the 2004 Aytes Memo to this effect:

In matters relating to an extension of nonimmigrant petition validity involving the same parties (petitioner and beneficiary) and the same underlying facts, a prior determination by an adjudicator that the alien is eligible for the particular nonimmigrant classification should be given deference. A case where a prior approval of the petition need not be given deference includes where: (1) it is determined that there was a material error with regard to the previous petition approval; (2) a substantial change in circumstances has taken place; or (3) there is new material information that adversely affects the petitioner’s or beneficiary’s eligibility.

In short, the 2004 guidance stated that, where the petitioner and beneficiary were unchanged from the initial petition and the underlying facts were identical, a USCIS officer should defer to the initial petition determination in adjudicating the extension petition. However, where it was determined that the initial petition had been approved in error, where the underlying facts were different, or where new information had become available, the approvability of the extension petition was called into question, and the USCIS officer need not afford deference to the initial petition determination. Section VII of the 2015 L1B Memo included what was effectively the same guidance for L1B petitions.

USCIS’s Reasons For Change in Policy

The 2017 Memo then states that it is rescinding the policy from the 2004 Aytes Memo and the 2015 L1B Memo (L1B-specific) that required adjudicators to defer to prior determinations in most extension petitions. Please note that this leaves most of the 2015 L1B Memo unaffected. It states that the updated guidance would be “more consistent with the agency’s current priorities and also advance[] policies that protect the interests of U.S. workers.”

The 2017 Memo cites to Chapter 10.3(a) of the Adjudicator’s Field Manual (AFM), which requires adjudicators to always thoroughly review a petition and supporting evidence to determine eligibility for the requested benefit. Under section 291 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), the burden of proof rests with the petitioner.

In the 2017 Memo, the USCIS takes the position that the 2004 Aytes Memo improperly shifted the burden of proof from the petitioner to the USCIS. Specifically, it concludes that “[t]he fundamental issue with the April 23, 2004 memorandum is that it appeared to place the burden on USCIS to obtain and review a separate record of proceeding to assess whether the underlying facts in the current proceeding have, in fact, remained the same.” In addition to finding that this policy was contrary to section 291 of the INA, the USCIS states that “it was also impractical and costly to properly implement, especially when adjudicating premium processing requests.”

New Policy

The 2017 Memo clarifies that the burden of proof always rests with the petitioner, including the filers of extension petitions. To support this posture, the Memo cited to 8 C.F.R. 103.2(b)(1), which requires the petitioner to establish that he or she is eligible for a benefit at the time of filing for the benefit, and such eligibility must continue through adjudication. Furthermore, it cited to 8 C.F.R. 214.1(c)(5), which states that an extension request may be approved in the discretion of USCIS where an applicant or petitioner demonstrates eligibility.

The 2017 Memo notes that the 2004 Aytes Memo did acknowledge that the USCIS has the authority to review prior decisions and deny requests for extensions of status. To that effect, the 2017 Memo preserves and incorporates the following guidance from the 2004 Memo, which remains binding on all USCIS officers:

[US]CIS has the authority to question prior determinations. Adjudicators are not bound to approve subsequent petitions or applications seeking immigration benefits where eligibility has not been demonstrated merely because of a prior approval which may have been erroneous. Matter of Church Scientology Intl, 19 I&N Dec. 593, 597 (Commissioner 1988) [PDF version]. Each matter must be decided according to the evidence of record on a case-by-case basis. See 8 C.F.R. [sec.] 103.8(d) [(2011)].

However, other than the one passage it opts to preserve, the 2017 Memo takes the position that the 2004 Aytes Memo “unduly limited adjudicator’s fact-finding authority in certain cases.” In laying out the new policy, the 2017 Memo states that the fact-finding authority of USCIS officers should not be constrained by the fact that a prior petition was approved.

The 2017 Memo acknowledges that petitioners for extensions are, under the regulations, not required to submit initial evidence in certain cases. It cited to 8 C.F.R. 214.2(h)(14) (H1B), (l)(14)(i) (L1), (o)(11) (O), and (p)(13) (P) as the primary examples for common nonimmigrant work visa categories. However, the 2017 Memo explains that these regulations only set the requirements for what a petitioner must submit at the time of the filing of an extension petition. It notes that the regulations do not limit the USCIS’s authority to request further evidence and, in fact, reiterate this authority. The 2017 Memorandum instructs adjudicators to be aware of the aforementioned regulations and cognizant of the fact that, while they do not require supporting documents as initial evidence for certain extension petitions, adjudicators “should not feel constrained in requesting additional documentation in the course of adjudicating a petition extension, consistent with existing USCIS policy…” The 2017 Memo makes clear both that it does not require adjudicators to request more evidence, and that “[w]hile adjudicators may, of course, reach the same conclusion as in a prior decision, they are not compelled to do so as a starting point.”

The 2017 Memo asserts that because the 2004 policies were “viewed as a default position upon beginning review of a filing,” they may have “limit[ed] the ability of adjudicators to conduct a thorough review of the facts and assessment of eligibility in each case.” This may have led, according to the 2017 Memo, to “the unintended consequence of not discovering material errors in prior adjudications.”

Interestingly, the 2017 Memo also made clear that it does not require adjudicators to request more evidence. It stated that “[w]hile adjudicators may, of course, reach the same conclusion as in a prior decision, they are not compelled to do so as a starting point.”

Note on 2004 Aytes Memo

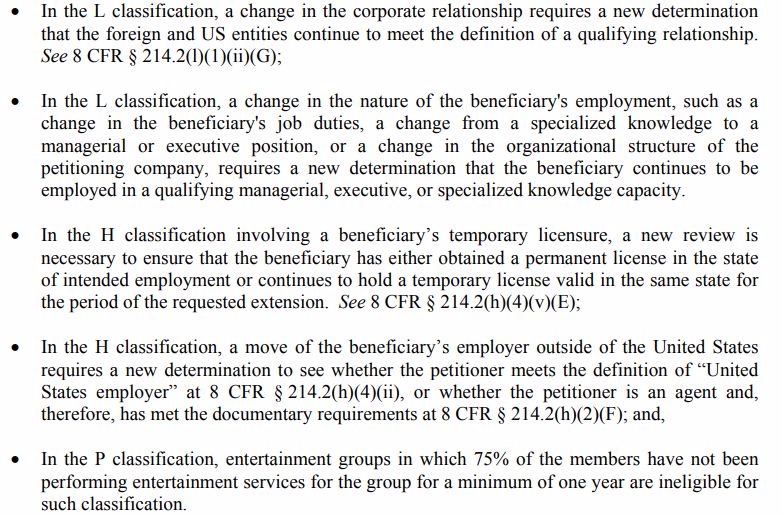

Although the 2004 Aytes Memo has been rescinded, petitioners should continue to bear in mind one portion of it. The 2004 Aytes Memo stated that in situations where there have been a substantial change in circumstances from the initial petition, the adjudicators need not defer to a previous determination. Since the 2017 Memo broadens the situations in which such deference need not be afforded, it continues to be true that situations where there is a substantial change in circumstances will merit further review of the petition. Petitioners in these cases will always have to submit evidence to show that the requirements for approval are still met. We have reproduced the 2004 Aytes Memo’s non-exhaustive list of change in circumstances below for some examples:

[Click image to view full size]

Furthermore, it goes without saying that when it is determined that there was a material error in the approval of an initial petition or if there is new material information that was not available to a previous adjudicator, such petitions will likely merit more scrutiny than when the parties and facts are unchanged. However, the significant difference in the new policy is that even when the parties and facts are unchanged adjudicators examining extension petitions now have greater latitude to question the conclusions underlying the approval of the initial petition and to require the submission of evidence.

Conclusion

In the now-rescinded 2004 Memo, Michael Aytes wrote the following in explaining the purpose of issuing the policy:

[A] recent review of [US]CIS practices has shown that in certain instances, adjudicators have been questioning prior determination where there is no material change in the underlying facts as a matter of routine…

This indicates that before the 2004 policy was in place top immigration officials recognized that officers adjudicating extension petitions would often question the determination regarding the approval of the initial petitions when the underlying facts were unchanged. With the 2004 policy now reversed, it is quite possible that similarly situated petitioners will face requests for evidence and more scrutiny than they did under the rules that had been place since 2004. However, the requirement that the petitioner must meet a burden of proof for extension petitions remains unchanged. Petitioners and beneficiaries should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for guidance on meeting all of the requirements for a nonimmigrant visa petition based on the facts of the individual case and the benefit sought.