Introduction

On December 29, 2017, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) issued a Policy Memorandum (PM) titled “L-1 Qualifying Relationships and Proxy Votes” (PM-602-0155) [PDF version]. The memorandum clarifies that to establish a qualifying relationship for an L1 nonimmigrant visa petition between a foreign entity and the U.S. petitioner, proxy votes (where applicable) “must be irrevocable from the time of filing the L-1 petition through adjudication…” The memorandum serves to clarify a published administrative precedent decision — Matter of Hughes, 18 I&N Dec. 289 (Comm’r 1982) [PDF version] — which addressed several scenarios involving qualifying relationships for L1 purposes, but which did not set guidelines for proxies. Please note that the guidance applies equally in the L1A executive and manager [see category] and L1B specialized knowledge [see category] contexts.

In this article, we will examine the new USCIS policy for proxies in the L1 context. Please see our wide selection of L nonimmigrant visa category articles to learn more about related issues [see category].

Policy Background

The memo begins by explaining the basic background of the L1 category.

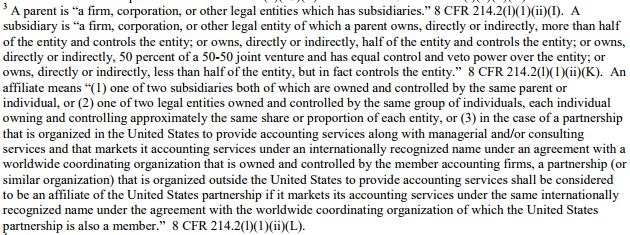

In order to transfer an employee to work in the United States on L1 status, a foreign employer must have a “qualifying relationship” with what would be the beneficiary’s petitioner and U.S. employer. What is a “qualifying relationship”? Under 8 C.F.R. 214.2(l)(1)(i), the U.S. petitioner may be the parent, branch, subsidiary, or affiliate of the foreign employer. Thus, as the memo explains, “[t]o establish a ‘qualifying relationship,’ the petitioner must show that it and the beneficiary’s foreign employer are either the same employer, for example, a U.S. entity with a foreign branch office or, alternatively, related as a ‘parent and subsidiary’ or as ‘affiliates.’” Footnote 3 of the memorandum details the regulatory definitions of the pertinent terms:

[Click image to view full size]

Please note that there are many other requirements for L1 status, such as the requirement that the petitioner be a “qualifying organization” as defined in 8 C.F.R. 214.2(l)(1)(i) (see ftn 2 of the memo). However, in this article, we will examine only certain provisions for the qualifying relationship requirement (see our L1 overview for further discussion of other petitioner requirements [see article]).

The memo explains that the USCIS must consider the following factors when determining whether the requisite qualifying relationship exists between the petitioner and the beneficiary’s foreign employer:

1. Ownership, meaning “the legal right of possession with full power and authority to control”; and

2. Control, meaning “the right and authority to direct the management and operations of the business entity.”

The USCIS cited to the Matter of Hughes and the administrative precedent decisions of Matter of Church Scientology Int’l, 19 I&N Dec. 593 (Comm’r 1988) [PDF version], and Matter of Siemens Med. Sys. Inc., 19 I&N Dec. 362 (Comm’r 1986) [PDF version].

The three decisions noted above “addressed the necessary corporate relationship for intracompany transfers…” In Matter of Hughes, the then-Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) addressed joint-venture situations, and, as the USCIS notes, “provided an extensive analysis of the meaning of affiliation for L-1 purposes.” The USCIS memo quoted from Matter of Hughes, 18 I&N Dec. at 292-93: “In order to be deemed affiliates, companies should be bound to one another by substantial, but not necessarily majority, ownership of shares…” The INS continued by holding that “affiliation requires that the financial link between two entities involve control by one over the management of another.”

While Matter of Hughes laid the groundwork for adjudicating joint-venture scenarios in the L1 context, the USCIS notes that it did not address other scenarios, such as where “owners of entities … use proxy votes to determine control of the entity.” Furthermore, subsequent USCIS guidance that built on Matter of Hughes also did not address proxy vote scenarios.

New Policy on Proxy Vote Scenarios

The USCIS explained that “[g]enerally, a proxy can be revoked at any time, unless it is coupled with an interest or made expressly irrevocable.” The USCIS detailed two situations where a proxy could be revoked:

“Depending on the specific jurisdiction governing the entity in which a proxy has been granted, the sale of an equity holder’s entity may automatically revoke any proxies previously given to vote that equity”; or

“A proxy may also be revoked when the equity holder gives a subsequent proxy covering the same equity or attends a meeting to vote the equity in person.”

The USCIS noted that situations where proxies may be revoked is an issue if the petitioner is relying on proxy votes to satisfy the L1 requirements. To this effect, the memo noted that, while majority ownership is not required to establish a qualifying relationship, 8 C.F.R. 214.2(l)(1)(ii)(L) does require that affiliates share both common ownership and control.

Accordingly, the memo stated that in proxy vote scenarios, “a petitioner can show control by submitting documentation demonstrating that one or more equity holders irrevocably granted the abilityto vote their equity to another equity holder, thereby effectively (and legally) giving the equity holder ‘control’ over the company or companies in question” (emphasis added). Here, the USCIS staked its position that, in order to rely on proxies to establish control, the proxies must be irrevocable. How can a petitioner establish an irrevocable proxy? The memo offered a non-exhaustive list of possible evidence:

Relevant evidence regarding the legal framework under which the proxy was granted;

The organization documents of the entity;

Irrevocable proxy agreements;

Official meeting minutes detailing the irrevocable proxy;

An affidavit from the proxy-granting equity holder with sufficient specificity regarding the details of the proxy; and

Other relevant evidence.

All evidence submitted by the petitioner must be “credible and sufficient for the adjudicator to determine eligibility.” The USCIS noted that the petitioner bears the burden of proof for establishing eligibility.

The memo made explicit that “to establish a qualifying relationship in situations where the petitioner has submitted documentation of control by proxy votes, the petitioner must show that the proxy votes are irrevocable from the time of filing the L-1 petition through the time of adjudication…” (emphasis added). Furthermore, the memo added that “[s]uch approval is further conditioned on evidence demonstrating that the qualifying relationship will continue to exist during the [petition] approval period requested.”

If there are changes to ownership and control after the USCIS adjudicates a petition, the petitioner is then required to file an amended petition. The memo concluded by noting that “such changes may constitute a substantial change in circumstances or represent new material information.”

Conclusion

The memo sets rules for a specific scenario where an L1 petitioner seeks to establish control of a business entity through proxy votes. In the L1 context, the memo makes clear that the proxy votes must be irrevocable from the filing of the L1 petition through its adjudication. Furthermore, the petitioner must establish that the qualifying relationship between it and the foreign employer will continue to exist throughout the petition approval period.

In addition to setting rules for establishing control through proxy votes, the memo provides limited guidance on the types of evidence that a petitioner may submit to establish that the proxies were irrevocable. As in all cases, an L1 petitioner should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance based on the facts of the petitioner’s situation and the most current rules, regulations, and guidance regarding L1 petitions.