- Introduction: Matter of Song, 27 I&N Dec. 488 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 488-89

- Respondent Appeals and Issue: 27 I&N Dec. at 489

- Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 489-93

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Song, 27 I&N Dec. 488 (BIA 2018)

On November 19, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) published an administrative precedent decision in Matter of Song, 27 I&N Dec. 488 (BIA 2018). The decision dealt with the eligibility for adjustment of status of an alien who had been admitted into the United States on a K1 fiancé visa, who had fulfilled the terms of the K1 visa, and who had subsequently divorced the petitioner. The Board held that an adjustment applicant in this scenario “must submit an affidavit of support from the petitioner to establish that he or she is not inadmissible as a public charge under section 212(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act” (INA).

In this article, we will discuss the factual and procedural history in Matter of Song, the Board’s analysis and conclusions, and what the decision means going forward. We discuss K1 visas in detail in a separate article. To learn more about important administrative precedent decisions in immigration law, please see our growing article index on the subject.

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 488-89

The respondent, a native and citizen of Cambodia, entered the United States as a K1 nonimmigrant fiancée on November 25, 2011. She married the petitioner within 90 days of admission in accordance with the K1 visa requirements.

On February 3, 2012, the respondent filed for adjustment of status with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) based on her marriage to a U.S. citizen. She filed a Form I-864, Affidavit of Support Under Section 213A of the INA, executed by the petitioner, along with her adjustment application.

While the respondent’s adjustment of status application was pending, her marriage to the petitioner broke down. On July 10, 2012, the petitioner wrote to the USCIS to withdraw his affidavit of support. Months later, on November 21, 2012, the USCIS denied the respondent’s adjustment of status application upon finding that the respondent was inadmissible under section 212(a)(4) of the INA as an alien who was likely to become a public charge.

On December 20, 2012, the respondent and her husband divorced. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) then initiated removal proceedings against the respondent under section 237(a)(1)(B) of the INA as an alien who had remained in the United States longer than permitted.

In removal proceedings, the respondent renewed her application for adjustment of status before the Immigration Judge. In support of her application, she submitted a new affidavit of support which was executed by a family friend. The Immigration Judge denied the adjustment application, finding that although the respondent was not precluded from eligibility for adjustment solely because of her divorce, she was nevertheless required to submit an affidavit of support from the petitioner — her former husband. Because the respondent could not submit an affidavit of support executed by her former husband, the Immigration Judge concluded that she was inadmissible on public charge grounds.

Respondent Appeals and Issue: 27 I&N Dec. at 489

The respondent appealed from the Immigration Judge’s decision to the BIA.

The Board summarized the issue presented: “The issue before us is whether an applicant for adjustment of status who was admitted on a valid K-1 nonimmigrant visa, fulfilled the terms of the visa by marrying the petitioner, and was later divorced must submit an affidavit of support from the petitioner to establish that he or she is not inadmissible as a public charge.”

For the reasons which we will examine in the subsequent section, the Board would affirm the Immigration Judge’s decision in concluding that a K1 adjustment applicant situated in the same manner as the respondent is required to submit an affidavit of support from the petitioner (former husband or wife) to overcome the presumption of public charge.

Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 489-93

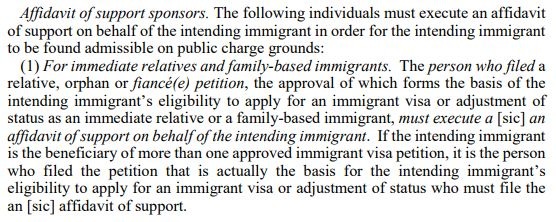

Under section 212(a)(4)(C)(ii) of the INA, an alien with immediate relative status or family-based preference classification is inadmissible on public charge grounds under section 212(a)(4)(B)(i)(IV) unless “the person petitioning for the alien’s admission … has executed an affidavit of support … with respect to such alien.” Under DHS regulations in 8 C.F.R. 213a.2(b) (2018), beneficiaries of K1 fiancé(e) petitions are explicitly made subject to the section 212(a)(4)(B)(i)(IV) requirement. The Board excerpted the pertinent regulatory provision:

Before the Board, the respondent argued that it was unreasonable for Congress to require a K1 fiancé(e) visa holder, who had complied with the terms of his or her visa but had subsequently divorced, to provide an affidavit of support only from the petitioner (in that case, the former spouse). The Board would, for the following reasons, conclude that the respondent’s “assertion is inconsistent with the plain language of the statute and regulations.”

The Board explained that there has been a public charge-related ground of inadmissibility “[f]or well over 100 years…” The concept of the legally binding affidavit of support, however, was only introduced in 1996 and implemented in 1997.

Under current rules, the sponsor of a fiancé or other alien relative is not obligated to submit an affidavit of support. However, the Board explained that “if a sponsor chooses to facilitate the immigration of such a relative, he or she must comply with the legal requirements for doing so.” Under 8 C.F.R. 213a.2(b)(1) and administrative guidance, one of these requirements is the submission of a properly executed affidavit of support.

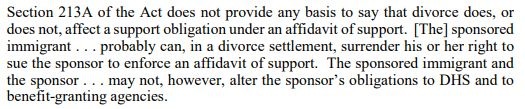

8 C.F.R. 213a.2(d) makes clear that the affidavit of support is a legally binding contract. The sponsor assumes certain obligations with the submission of an affidavit of support. The most recent affidavit of support regulations were published at 71 FR 35,732 (June 21, 2006) (final rule). At page 35,740 of the rule, the DHS addressed situations where the alien and sponsor divorce. The Board excerpted the pertinent passage, reproduced below for your convenience:

The Board noted that the regulatory language “lends support to the understanding that Congress intended the affidavit of support to be a legally binding commitment, unaltered by the circumstance of the divorce.” While the sponsored immigrant may forego the right to sue the sponsor if he or she does not follow through on the affidavit of support, the fact of divorce “may not … alter the sponsor’s obligations to DHS and to benefit-granting agencies.” The Board added that this language is also reflected in the Form I-864 instructions in effect at the time of the decision.

Under section 8 C.F.R. 213a.2(f) and USCIS agency guidance, the sponsor may withdraw an affidavit of support prior to the adjudication of the adjustment application. The Board reasoned that it is not “a foregone conclusion that a sponsor will withdraw his or her affidavit of support for a spouse upon their divorce.” In the same manner that an alien may forego his or her right to sue for enforcement of the affidavit, the sponsor may agree to not withdraw the affidavit. The Board wrote that this “possibility supports our conclusion that the plain language of the statute and regulations does not permit an exception to the affidavit of support requirements in the event of divorce and that none should be implied.”

Furthermore, the Board then looked to the INA itself, which does, in fact, provide for only two explicit exceptions to the affidavit of support requirement. Under section 204(a)(1)(A)(iii), (iv) of the INA, an alien who is or was married to an abusive spouse is not required to provide an affidavit of support from the abusive spouse. Under section 213A(f)(5)(B)(i) of the INA, where the petitioning spouse died prior to adjudication of the adjustment application, the beneficiary may substitute the petitioner’s affidavit of support with an affidavit from another qualifying relative.

The Board found these two exceptions significant in that they “highlight[ed] the absence of any others.” In TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U.S. 19, 28 (2001), the Supreme Court of the United States wrote that “[w]here Congress explicitly enumerates certain exceptions to a general prohibition, additional exceptions are not to be implied, in the absence of evidence of contrary legislative intent.” In the instant case, the Board explained, “Congress could have made an exception for the divorce of a K-1 visa holder, but it did not.” In the absence of any such exception, the Board referred to the general affidavit requirement in section 212(a)(4)(C)(ii) of the INA — as implemented in regulations at 8 C.F.R. 213a.2(b)(1) — in stating that “Congress clearly indicated its intent that the sponsor who brought the alien to the United States must be financially responsible for the alien through the period of his or her adjustment of status.”

The respondent argued that the Board should follow its prior precedent in Matter of Sesay, 25 I&N Dec. 431, 440-41 (BIA 2011), wherein it concluded that the K1 visa-holder in that case could adjust status despite his divorce from the petitioner if he was otherwise admissible. The Board in Matter of Sesay stated, however, that “the regulations were silent regarding the termination of a valid marriage…” Id. In contrast, in the instant case the regulation at issue was clear: “8 C.F.R. 213a.2(b)(1) affirmatively states that a fiancé(e) petitioner must be the person who files an affidavit of support on behalf of the K-1 visa holder.” Moreover, under section 212(a)(4)(C)(ii) of the INA and 8 C.F.R. 213a.2(f), the applicant is inadmissible “if the petitioner declines to submit an affidavit of support or withdraws it before the alien’s adjustment application has been adjudicated.” The Board stated that because the statutory and regulatory language was “plain and unambiguous,” it was bound to follow it, regardless of any other considerations.

The Board then applied its reasoning to the facts of the instant case. The Board explained that, while the respondent was not ineligible for adjustment per se, she was inadmissible until she could provide an affidavit of support from her sponsor. Because the respondent acknowledged in immigration proceedings that she did not have an affidavit of support from her sponsor, the Board held that “the Immigration Judge properly found her to be inadmissible and therefore ineligible for adjustment of status.” For this reason, the Board dismissed the appeal.

Conclusion

The Board’s decision in Matter of Song is significant in the K1 visa context. In the decision, the Board definitively held that the statutes and regulations necessitate the conclusion that a K1 adjustment applicant requires an affidavit of support from his or her sponsor, absent a battered spouse or widower exception. Because divorce is not covered by an exception in the statutes or regulations, the K1 adjustment applicant still requires an affidavit of support from his or her petitioning former spouse in order to adjust status, notwithstanding otherwise having met all other requirements.

An alien seeking adjustment of status and/or facing removal should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance. We discuss K1 visas in detail in a separate article. To learn more about public charge, please see our full article index on the subject. To learn more about other issues addressed in this article, please see our website’s growing categories on family immigration, adjustment of status, and removal and deportation defense.