- Introduction: Matter of L-M-P-, 27 I&N Dec. 265 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 265-266

- Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N at 266-70

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of L-M-P-, 27 I&N Dec. 265 (BIA 2018)

On April 27, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published for-precedent decision in the Matter of L-M-P-, 27 I&N Dec. 265 (BIA 2018) [PDF version].

Matter of L-M-P- involved the denial by an Immigration Judge of a motion by Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) to reconsider its decision to grant asylum to an applicant who was subject to a reinstated removal order under section 241(a)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and who had been placed in withholding of removal only proceedings. First, the Board held that the DHS has the authority to file a motion to reconsider under regulations promulgated by the Attorney General. Second, the Board held that an applicant in withholding of removal proceedings who is subject to a reinstated removal order under section 241(a)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) is ineligible for asylum.

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of Matter of L-M-P-, the Board’s analysis and conclusions, and what the new precedent means going forward.

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 265-266

The case concerns an applicant who had been granted asylum in withholding of removal only proceedings after having been subject to a reinstated removal order.

The applicant, a native and citizen of Guatemala, was removed from the United States on August 6, 2013. He illegally re-entered the United States four days later, on August 10, 2013. On August 15, 2013, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reinstated the prior order of removal against the applicant under section 241(a)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). After being apprehended, the expressed a fear of returning to Guatemala and was referred to an asylum officer for a reasonable fear interview under 8 C.F.R. 1241.8(e) (2014) . The asylum officer referred the matter to the Immigration Judge under 8 C.F.R. 1208.31(e) for withholding of removal only proceedings after concluding that the respondent had a reasonable fear of persecution.

On August 1, 2016, the Immigration Judge granted the applicant’s application for asylum, notwithstanding the fact that the respondent had a reinstated removal order and had been placed in withholding of removal only proceedings.

On August 31, 2016, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued a precedent decision in Perez-Guzman v. Lynch, 835 F.3d 1066 (9th Cir. 2016) [PDF version], cert. denied, 138 S.Ct. 737 (2018). In Perez-Guzman, the Ninth Circuit held that an alien who is subject to a reinstated removal order is not eligible for asylum. In so doing, the Ninth Circuit gave administrative (Chevron) deference to the regulations implementing conflicting INA provisions on the issue. This decision was especially significant in the instant case because the proceedings arose in the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit.

On the same day that Perez-Guzman was published, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) filed with the immigration court a timely motion to reconsider the order granting asylum The DHS argued that the Ninth Circuit’s holding in Perez-Guzman had clarified that the Immigration Judge’s decision to grant the applicant asylum was impermissible because she was subject to a reinstated order of removal under section 241(a)(5).

The Immigration Judge denied the DHS’s motion to reconsider. In so doing, the Immigration Judge held that the INA does not permit DHS to file a motion to reconsider, and the regulation stating otherwise at 8 C.F.R. 1003.23(b)(1) (2016) was inconsistent with the INA. Because the Immigration Judge concluded that the DHS was barred by statute from filing a motion to reconsider, the motion itself was denied. The Immigration Judge also held, in the alternative, that the DHS’s motion to reconsider was barred by res judicata (the principle that a case that has already been adjudicated to final judgment is no longer subject to further appeal or adjudication).

The DHS appealed from the Immigration Judge’s decision to the BIA.

Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N at 266-70

The Board ultimately sustained the DHS’s appeal and remanded the record to the Immigration Judge. As we will see in the subsequent sections, the Board accepted the DHS’s arguments that the Immigration Judge was bound to follow the regulations allowing the DHS to file motions to reconsider and that the DHS’s motion was not barred by res judicata. Having reached those conclusions, the Board finally concluded that the Immigration Judge erred in granting the applicant asylum. We will examine the Board’s analysis and conclusions on each of these points in turn.

DHS Has Authority to File Motion to Reconsider: 27 I&N Dec. at 266-68

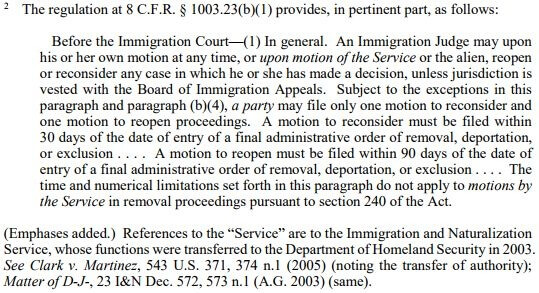

The Board began by stating that 8 C.F.R. 1003.23(b)(1) “explicitly gives the DHS authority to seek reconsideration and reopening in Immigration Court.” Below is the text of the regulation with notes as excerpted by the Board at 27 I&N Dec. at 266 n.2:

The Board discussed the breadth of the regulation, explaining that it “specifically states that an Immigration Judge can reopen or reconsider any case upon a motion of the DHS or an alien and that the DHS is not subject to the time and numerical limits for such motions in removal proceedings.” The Board concluded that the plain language of the regulation makes it clear that “both the DHS and the alien are permitted to file motions to reconsider and reopen before the Immigration Judge.

Contrary to the view of the Immigration Judge in the instant case, the Board reaffirmed its rule that “[a]n Immigration Judge is without authority to disregard the regulations, which have the force and effect of law.” In Matter of H-M-V-, 22 I&N Dec. 256, 261 (BIA 1998) [PDF version], the Board held that “once a regulation is properly issued by the Attorney General, it is the obligation of this Board and the Immigration Judges to enforce it. Regulations promulgated by the Attorney General have the force and effect of law as to this Board and the Immigration Judges.” The Board had previously held the same in Matter of Fede, 20 I&N Dec. at 35-36 (BIA 1989) [PDF version], where it concluded that “[a] regulation promulgated by the Attorney General has the force and effect of law as to immigration judges and the Board of Immigration Appeals.”

The Board concluded that, based on the clear language of the regulation and the fact that the Immigration Judge had no authority to disregard the regulation, the Immigration Judge erred in concluding that the DHS was without authority to file a motion to reconsider. The Board could have ended its analysis on the issue here. However, it opted to additionally respond to the Immigration Judge’s extensive analysis of the purported conflict between the statute and the 8 C.F.R. 1003.23(b)(1).

The Board explained that section 240(c)(6)(A) of the INA reads as allowing an “alien to file one motion to reconsider a decision that the alien is removable from the United States.” The Board acknowledged that the statute only contains a reference to “the alien.” However, it disagreed with the conclusion of the Immigration Judge that the language of section 240(c)(6)(A) “clearly and unambiguously grants the right to file a motion to reconsider to aliens alone” (Board’s summary of the Immigration Judge’s position). Instead, the Board took the position that section 240(c)(6)(A) expressly defines and limits only the alien’s ability to file motions to reconsider. In light of this reading, the Board concluded that “the absence of any similar limitations on the DHS could be interpreted as meaning that Congress intended that the DHS be unencumbered by any limitations on its ability to file motions.” Accordingly, the Board concluded that the language of section 240(c)(6) was ambiguous, meaning that there was more than one plausible reading of the statute. The Board then moved to explain why the regulation was a reasonable construction of the statute and, further, was the construction most in accord with the purpose of the statute.

The Board rejected the Immigration Judge’s conclusion that the legislative history of section 240(c)(6) suggested that the provision was intended to only allow the alien to file motions to reopen or reconsider and to preclude the DHS from filing any such motions. Citing to the legislative history, the Board noted that committee reports on the statute stated that the purpose of the provision was to streamline the removal process and limit the avenues by which aliens could seek relief from deportation while making it easier to remove deportable aliens. Furthermore, the committee report elaborated that the intent of section 240(c)(6) was to limit the alien’s ability to file motions to reopen and reconsider. To see the specific quotes and citations, please consult the decision at 27 I&N Dec. at 267-68.

The Board then discussed interim regulations implementing section 240(c)(6) at 62 FR 10312, 10321 (Mar. 6, 1997) (codified at 8 C.F.R. 3.23(b) (1998)). The then-Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) had acknowledged that several commenters to the proposed rule had argued that the limitation of a single motion to reopen or reconsider for the alien should apply to all parties in proceedings. The INS rejected this suggestion, stating that “Congress has imposed limits on motions to reopen, where not existed by statute before, and specifically imposed those limits on the alien only.” (Emphasis added by the Board.) It was for this reason that INS incorporated the statutory numerical limit on motions to reopen and reconsider on aliens by expressly exempting the Government from the same limitations on motions in removal proceedings.

In a final point, the Board noted that under 8 C.F.R. 1003.23(b)(2), the purpose of a motion to reopen or to reconsider is to address any “errors of fact or law in the Immigration Judge’s prior decision.” The Board had held in Matter of Cerna, 20 I&N Dec. 399, 402 (BIA 1991) [PDF version], that “[t]he very nature of a motion to reconsider is that the original decision was defective in some regard.” Based on the purpose of the motion to reconsider, the Board concluded in the instant case that “[t]here is no logical rationale that only one party is permitted to seek the correction of a defective decision.”

DHS’s Motion Not Barred by Res Judicata: 27 I&N Dec. at 268-69

The Immigration Judge had offered an alternative reason for denying the Board’s motion to reconsider — that it was barred by res judicata. The Board defined the principle res judicata in Matter of Jasso Arangure, 27 I&N Dec. 178, 180 (BIA 2017) [PDF version], as where “a final judgment on the merits bars a subsequent action between the same parties over the same cause of action.” Please see our full article on Matter of Jasso Arangure to learn more about this important precedent [see article].

Regarding the instant case, the Board found that the DHS had filed a timely motion to reconsider in accordance with the implementing regulations. Under 8 C.F.R. 1003.23(b)(1), the Immigration Judge does not have jurisdiction over a motion to reconsider if jurisdiction in the matter has already vested in the Board. However, in the instant case, jurisdiction had not vested with the Board and the DHS filed its motion prior to the expiration of its appellate deadline. For these reasons, the Board concluded that the Immigration Judge had jurisdiction over the DHS’s motion.

The Board then explained that withholding of removal proceedings are subject to a timely motion to reconsider. Because the window for filing a timely motion to reconsider had not expired, “the administrative process provided by the regulations had not been completed.” For this reason, the Board concluded that the doctrines of res judicata and collateral estoppel did not apply at all in the instant case. The Board agreed with the DHS’s contention that under the reasoning employed by the Immigration Judge, res judicata “would bar timely movants from filing their motions” that they were otherwise entitled to file. It further cited to Valencia-Alvarez v. Gonzales, 469 F.3d 1319, 1323-24 (9th Cir. 2006) [PDF version], wherein the Ninth Circuit did not accept a res judicata argument where the alien had not obtained a prior “final judgment, rendered on the merits in a separate action.”

In the res judicata analysis, the Immigration Judge had relied on the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Guevara v. Gonzales, 450 F.3d 173 (5th Cir. 2006) [PDF version]. However, the Board found that this decision was clearly distinguishable from the situation in the instant case. Specifically, the DHS had filed its motion to reconsider more than two years after the Board had terminated removal proceedings in that case. Conversely, in the instant case, the DHS filed a timely motion to reconsider with the Immigration Judge and did so in accordance with the applicable regulations.

The Board also rejected the Immigration Judge’s reliance on the Supreme Court of the United States decision in Stone v. INS, 514 U.S. 386, 401 (1995) [PDF version], which addressed res judicata in the context of Federal court jurisdiction. Notably, in Sosa-Valenzuela v. Holder, 692 F.3d 1103, 1111 (10th Cir. 2012) [PDF version], the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit held that Stone does not restrict appellate jurisdiction over Board decisions. In Matter of Jasso Arangure, 27 I&N Dec. at 181, the Board took the position that res judicata applies more flexibly in administrative proceedings than in judicial proceedings. In an additional point, the Board in the instant case took the position that Stone, 514 U.S. at 401, also supported the notion “that an individual who seeks reconsideration of an Immigration Judge’s decision, rather than appealing, may challenge the issues underlying the motion to reconsider despite the subsequent finality of the decision…”

Immigration Judge Erred in Granting Asylum in Withholding of Removal Only Proceedings: 27 I&N Dec. at 269-70

Finally, the Board concluded that the Immigration Judge erred in granting the applicant asylum. Under 8 C.F.R. 1208.31(e), “If an asylum officer determines that an alien [who is subject to a reinstated removal order] has a reasonable fear of persecution or torture, the officer shall so inform the alien and issue a [referral to an immigration judge], for full consideration of the request for withholding of removal only.” (Emphasis added by the Board.) As we noted in the factual and procedural history section, the Ninth Circuit deferred to the Attorney General’s interpretation of the INA in 8 C.F.R. 1208.31(e). For these reasons, the Board concluded that the applicant was ineligible for asylum in withholding of removal only proceedings.

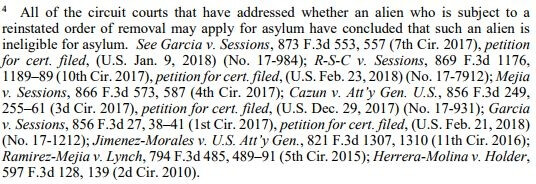

Interestingly, in a footnote, the Board noted that every Federal circuit court that has considered whether an alien who is subject to a reinstated removal order may apply for asylum has concluded that the alien may not. We have excerpted the relevant footnote below for your convenience:

Decision: 27 I&N Dec. at 269

The Board sustained the DHS’s appeal and vacated the Immigration Judge’s grant of asylum. However, the Board explained that the Immigration Judge had not addressed either the applicant’s application for withholding of removal or for protection under the Convention Against Torture. Accordingly, the Board remanded the record to the Immigration Judge for the purpose of considering the applicant’s eligibility for withholding of removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture.

Conclusion

In Matter of L-M-P-, the Board made clear that an Immigration Judge is bound to follow properly promulgated regulations, regardless of his or her opinion on whether they comport with the underlying statute. It was based, first, on this principle, even without the additional analysis, that the Board concluded that the DHS has the authority to file a motion to reconsider in Immigration Court. In its initial analysis, the Board read the INA’s exclusive mention of numerical restrictions on such motions by aliens as only applying a restriction to aliens rather than inferentially precluding the DHS from filing such motions. Furthermore, the Board held as precedent that an alien subject to a reinstated removal order is not eligible for asylum. This ruling does not represent a change in law due to the fact that it comports with the regulation and that every Federal circuit court that has considered the issue has deferred to the Government’s implementing regulations.

The case highlights that an alien facing a reinstated removal order has very limited avenues for relief from removal to a specific country. Any alien facing removal should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance.