- Introduction: Matter of Castillo Angulo, 27 I&N Dec. 194 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 194-95

- Explaining Charge Under INA 212 Instead of INA 237: 27 I&N Dec. at 195 n.1

- Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. 196-204

- “Wave Through” Entry Constitutes Being “Admitted”: 27 I&N Dec. at 196

- Issue and Arguments Pertaining to “Admitted in Any Status”: 27 I&N Dec. at 196-197

- Examining Legislative History and Congressional Intent: 27 I&N Dec. at 197-99

- Board Holds that “Admitted In Any Status” Requires Lawful Status: 27 I&N Dec. at 199-202

- Board Applies New Precedent Outside of Fifth and Ninth Circuits: 27 I&N Dec. at 202

- Applying the Rule of the Ninth Circuit to the Respondent: 27 I&N Dec. at 202-203

- Concurring and Dissenting Opinion: 27 I&N Dec. at 203-206

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Castillo Angulo, 27 I&N Dec. 194 (BIA 2018)

On January 29, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published for-precedent decision in Matter of Castillo Angulo, 27 I&N Dec. 194 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. The issue in Matter of Castillo Angulo addressed when an alien, who was “waved through” at a port of entry, has established admission “in any status,” as defined in section 240A(a)(2) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), for purpose of cancellation of removal for certain permanent residents. The Board held that, within the jurisdiction of the United States Courts of Appeals for the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, an alien who was “waved through” at a port of entry has established an admission “in any status” under section 240A(a)(2). The Board reached this conclusion because it was bound by precedent decisions of the Fifth and Ninth Circuits. However, the Board held that outside of the jurisdiction of the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, “an alien must prove that he or she possessed some form of lawful immigration status at the time of admission” in order to satisfy the “admitted in any status” requirement of section 240A(a)(2).

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of Matter of Castillo Angulo, the Board’s analysis and conclusions, and what the decision means going forward. In addition, we will also examine an interesting opinion concurring in part with and dissenting in part from the opinion of the Board in Matter of Castillo Angulo in a separate post [see article].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 194-95

The respondent, a native and citizen of Mexico, claimed that she first entered the United States in October 1991. In 2003, the respondent adjusted her status to that of lawful permanent resident.

On January 12, 2010, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent with the issuance of a notice to appear. The DHS charged the respondent with removability under section 212(a)(6)(E)(i) of the INA for smuggling or attempting to smuggle an alien into the United States. The respondent did not challenge the DHS’s additional charge that she was inadmissible under section 212(a)(6)(E)(i) or its treatment of her as an applicant for admission [see section].

In proceedings, the respondent conceded removability and sought to apply for cancellation of removal for certain permanent residents under section 240A(a)(2) of the INA. In order to establish eligibility for cancellation under this provision, an alien must establish that he or she accrued 7 years of continuous residence after having been “admitted in any status.” The Immigration Judge pretermitted (i.e., left unadjudicated) the respondent’s application for cancellation of removal because the Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent failed to establish that she “has resided in the United States continuously for 7 years after having been admitted in any status” as required under section 240A(a)(2) of the INA.

The respondent claimed that she had presented herself for inspection at the border in 1998, and that she was “waved through” a port of entry by an immigration official at the border. The respondent relied upon the Board’s decision in Matter of Quilantan, 25 I&N Dec. 285 (BIA 2010) [PDF version], in arguing that this being “waved through” at a port of entry constituted an admission “in any status” under section 240A(a)(2) of the INA. Accordingly, she argued, that she began to accrue continuous residence for purpose of cancellation of removal at the time of the wave-through entry.

The Immigration Judge rejected the respondent’s argument. In so doing, the Immigration Judge took the position that the Board’s decision in Matter of Quilantan only applies in the context of applications for adjustment of status under section 245(a) of the INA, and it does not apply in the context of section 240A(a)(2). Accordingly, the Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent’s “wave through” entry in 1998 was not an “admission” for purpose of section 240A(a)(2). The Immigration Judge thus found it unnecessary to determine whether the respondent had any status at the time of her entry since the Immigration Judge had already included that the respondent had not been admitted in 1998. The Immigration Judge determined that the respondent did not begin to accrue continuous residence until after her adjustment of status in 2003, meaning that she fell short of the 7-year continuous residence requirement.

The respondent appealed from the Immigration Judge’s decision to the BIA. The issue on appeal in the instant case was thus whether, as the respondent contended, the respondent had been “admitted in any status” when she had presented herself for inspection at the border and been waived through in 1998, in which event she would have met the continuous physical presence requirement for cancellation, or whether, as the immigration judge found, her admission transpired when she adjusted status in 2003, in which event she would fall short of the 7-year requirement. To this effect, it is important to note that the issuance of a notice to appear terminates the accrual of continuous residence.

During the appeal, the Board requested and received supplemental briefing on the issue [PDF version]. The Board heard oral arguments on in the case on March 22, 2017.

Explaining Charge Under INA 212 Instead of INA 237: 27 I&N Dec. at 195 n.1

One may note that the respondent was charged with inadmissibility under an inadmissibility provision rather than a deportability provision despite her being a lawful permanent resident. In most cases, lawful permanent residents are charged under the deportability provisions in section 237(a) instead of the inadmissibility provisions under section 212(a). However, the Board explained that the respondent did not challenge her treatment as an applicant for admission who was subject to inadmissibility grounds under section 212(a). Here, the Board cited to its decision in Matter of Guzman, 25 I&N Dec. 845 (BIA 2012) [PDF version], wherein it held that a lawful permanent resident who has attempted to smuggle an alien into the United States may be treated as an applicant for admission (specifically, this applies to a lawful permanent resident who engages in “illegal activity” at a port of entry).

Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. 196-204

In the following subsections, we will examine the Board’s analysis and conclusions. The sections are organized slightly differently in this article than they are in the decision for the purpose of enhancing readability.

“Wave Through” Entry Constitutes Being “Admitted”: 27 I&N Dec. at 196

The respondent relied upon Matter of Quiliantan to argue that her “wave through” entry in 1998 constituted an “admission” for purpose of section 240A(a)(2). The Board’s request for supplemental briefing asked the party and interested friends of the court for briefs on whether Matter of Quilantan applied in the cancellation of removal context.

The Board explained that in Matter of Quilantan, 25 I&N Dec. at 191-92, it held that “admission,” as defined in section 101(a)(13)(A) of the INA, requires procedural regularity. The Board adopted this reading as opposed to a stricter reading that would have required compliance with substantive legal requirements. Accordingly, the Board held in Matter of Quilantan that an alien who was “waved through” a port of entry had been “admitted” within the meaning of section 245(a) of the INA, pertaining to adjustment of status. The question in the instant case was whether Matter of Quilantan extends to the meaning of “admitted” in section 240A(a)(2), pertaining to cancellation of removal.

The Board concluded that its “holding in Matter of Quilantan governs the definition of the term “admitted” in section 240A(a)(2) of the [INA].” Accordingly, as a general rule, a “wave through” entry does constitute being “admitted” under section 240A(a)(2).

As applied to the instant case, the Board concluded that the respondent’s “wave through” entry in 1998 did constitute being “admitted” for purpose of section 240A(a)(2). The Board thus disagreed with the Immigration Judge and agreed with both parties on this point.

Issue and Arguments Pertaining to “Admitted in Any Status”: 27 I&N Dec. at 196-197

Under section 240A(a)(2), it is not sufficient for an applicant for cancellation to establish only that he or she was admitted. Instead, the requirement is “admitted in any status.” The Immigration Judge did not reach the question of whether the respondent had been admitted in “any status” because the Immigration Judge had determined that the respondent had not been admitted. However, since the Board reversed the Immigration Judge regarding the respondent’s having been admitted, the Board stated that “[t]he only remaining issue is whether a ‘wave through’ entry, like the one at issue in Quilantan, qualifies as an admission “in any status” within the meaning of section 240A(a)(2) [of the INA].”

The respondent took the position that her “wave through entry” was an admission “in any status.” To this effect, she argued that the word “any” encompassed all aliens admitted into the United States whether in lawful or unlawful status. In support of her position, the respondent cited to the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Tula-Rubio v. Lynch, 787 F.3d 288 (5th Cir. 2015) [PDF version]. In Tula Rubio, the Fifth Circuit explicitly held that a “wave through” entry satisfied the admission “in any status” requirement of section 240A(a)(2). However, the instant case arose in the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit, and not the Fifth, meaning that Tula-Rubio was not controlling. However, in an event that would prove to be fortuitous for the respondent, subsequent to oral arguments in the instant case, the Ninth Circuit held heldin Saldivar v. Sessions, 877 F.3d 812 (9th Cir. 2017) [PDF version] that a “wave through” entry constitutes admission “in any status.”

The DHS took the opposite position from that of the respondent, contending that the phrase “admitted in any status” requires that the alien not only establish that he or she was admitted, but also “that the admission was attained by means of some lawful immigration status.” (Emphasis added.) The Board had not issued any published decisions on the issue prior to the instant case.

Both the respondent and the DHS argued that the language of section 240A(a)(2) was unambiguous as to whether a “wave through” entry constitutes an admission “in any status.” The question before the BIA of whether the statutory language is ambiguous is pertinent to the Board’s discretion in considering the issue. In the statute was not ambiguous, the Board would be required read the statute in one way. However, if the statute was ambiguous, the Board, as an administrative agency, would have discretion under Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc. (“Chevron”), 467 U.S. 837, 842-43 (1984) [PDF version], to give statute a “reasonable” interpretation. Please see our article on a case currently pending before the Supreme Court to learn more about the Chevron precedent [see article]. The Board disagreed with both parties and concluded that the statute was “ambiguous” as to whether a “wave through” entry constitutes an admission “in any status.” Accordingly, it moved to develop a reasonable interpretation of section 240A(a)(2) while taking into account the INA as a whole.

Examining Legislative History and Congressional Intent: 27 I&N Dec. at 197-99

The Board first addressed how section 240A(a)(2) differs from section 245(a). In Matter of Quilantan, the Board had held that a “wave through” entry is sufficient for establishing an admission for the purpose of adjustment of status under section 245(a). However, the language of section 245(a) itself requires only that an alien have been “inspected and admitted” in order to be eligible for adjustment of status (note: an alien may also adjust under section 245(a) if he or she was paroled). Section 240A(a)(2) also requires that an alien have been “admitted,” but it adds the additional “in any status” requirement. The Board stated that to read section 240A(a)(2) the same as it read 245(a), which it read as requiring only “procedurally regular admission,” would render the phrase “in any status” in section 240A(a)(2) effectively meaningless.

While the Ninth Circuit ultimately read section 240A(a)(2) as requiring only procedurally regular admission, a dissenting opinion in Salvadar authored by then-Judge Alex Kozinski adopted the position that if Congress had intended for section 240(A)(a)(2) to require only a procedurally regular admission in order for an alien to be eligible for cancellation of removal, it would have omitted the “in any status” requirement. The Board agreed with the dissenting opinion in Salvadar, 877 F.3d at 819 (Kozinski, J., dissenting) and concluded “that section 240A(a)(2) requires something more than a procedurally regular ‘admission.’”

To discern the congressional intent regarding the requirement that an alien must be admitted “in any status,” the Board looked to the legislative history of both section 240A(a) and the statute it replaced, former section 212(c) [see article]. The Board explained that former section 212(c) had been restricted to aliens who were held some lawful status. The Board cited to several cases, including the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Lok v. INS, 548 F.2d 37, 41 (2d Cir. 1977) [PDF version]. The Board also cited to a Senate report from 1950 that suggested that former section 212(c) should include the word “lawful” to clarify that it was available only to aliens who had entered the United States lawfully. S. Rep. No. 81-1515, at 382-384 (1950).

The Board then stated that it found no indication that Congress had intended to eliminate the “lawful” entry requirement when it replaced former section 212(c) with current section 240A(a), wherein it imposed the “residence” requirement. The Board explained that Congress had enacted the “residence” requirement “to reconcile two conflicting interpretations of former section 212(c) regarding an applicant’s ‘lawful unrelinquished domicile’ in in the country.” To this effect, it cited to the Ninth Circuit decision in Garcia-Quintero v. Gonzales, 455 F.3d 1006, 1016 (9th Cir. 2006) [PDF version], abrogated on other grounds by Medina-Nunez v. Lynch, 788 F.3d 1103 (9th Cir. 2015). Notably, the Board held that neither of the conflicting interpretations of former section 212(c) allowed for aliens who entered without possessing a lawful status to be granted relief.

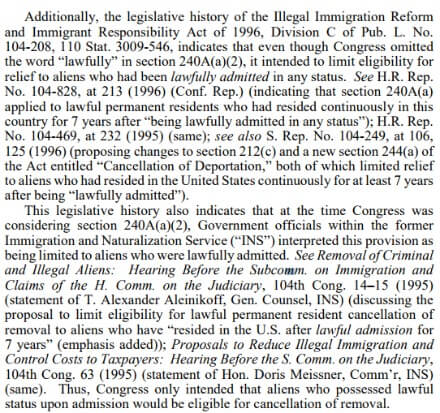

The Board then cited to several examples of legislative history that it felt buttressed its conclusion that Congress intended for admission “in any status” to entail lawful status. The legislative history pertains specifically to the enactment of section 240A(a)(2). You may read this section of the opinion below:

Board Holds that “Admitted In Any Status” Requires Lawful Status: 27 I&N Dec. at 199-202

Based on the language of 240A(a) itself, the language and interpretations of former section 212(c), and the legislative history of both former section 212(c) and current section 240A(a), the Board “conclude[d] that the most natural reading of the phrase ‘admitted in any status’ in section 240A(a)(2) of the [INA] is that the alien must have possessed some form of lawful status at the time of admission that would allow him or her to enter into the United States as an immigrant or nonimmigrant.” The Board also noted that this reading of the term “status” is consistent with its published decision in Matter of Blancas, 23 I&N Dec. 458, 460 (BIA 2002) [PDF version], wherein it held that the term “status” in section 240A(a)(2) “denotes someone who possesses a certain legal standing, e.g., classification as an immigrant or nonimmigrant.” The Board also noted that dissenting opinions in Salvidar and Tula Rubio adopted the same reading of “any status” as requiring “lawful” status. The Board stated that its conclusion in the instant case is “entirely consistent” with Matter of Quilantan. In Matter of Quilantan, 25 I&N Dec. at 293, the Board rejected the DHS’s argument that section 245(a) requires that an alien have been admitted in “lawful” status. However, the Board concluded that the “in any status” language of section 240A(a) made it distinguishable from section 245(a) in this regard.

The Board also discussed practical considerations for not permitting “wave through” entries to start the continuous residence clock for cancellation. The Board stated that allowing “wave through” entries to start the clock would “open[] the door for all lawful permanent resident aliens who illegally cross the border to claim, years after the fact, that they were ‘waved through’ a port of entry and are therefore eligible for cancellation of removal based on a claim that is impossible for the DHS to refute.” The Board explained that adopting the respondent’s position “would essentially relieve aliens of the statutory burden of establishing that he or she has satisfied all the eligibility requirements for cancellation of removal under 240A(a) of the [INA].” The Board considered it “unlikely” that this result would reflect Congressional intent to crafting section 240A(a).

The Board also disagreed with the Fifth (Tula-Rubio, 787 F.3d at 293-94 & n.5) and Ninth (Salvidar, 877 F.3d at 816) Circuits to the extent that they had held that an alien can be “admitted” in an unlawful status. The Board stated that an alien is only admitted “upon a determination that he or she is lawfully entitled to enter the United States.” The Board reasoned that, because the nature of the alien’s status determines whether he or she is entitled to admission, an alien cannot be “admitted in any status” that would not entitle him or her to admission. The Board also noted as significant to the issue before it that an alien may be admitted in error, and subsequently subject to removal under section 237(a)(1)(A) [see section] for having been inadmissible at the time of entry or adjustment of status.

The Board discussed several other issues it had with the reasoning of the Fifth and Ninth Circuits. We will address them only briefly here, but you may read them in more detail at 27 I&N Dec. at 201-202. First, the Board explained that the Fifth and Ninth Circuit readings holding that aliens could be admitted in unlawful status were would be in tension with sections 235(a)(3) and 212(a)(7) of the INA, both of which require aliens seeking admission to have valid entry documents. Second, the Board took the position that allowing the mistakes of border officials to trigger an alien’s eligibility for relief to be a peculiar result. Third, the Board took issue with the Fifth and Ninth Circuits using the existence of the phrase “lawfully admitted” in section 240A(a)(1) of the INA as relevant in light of the absence of “lawful” from section 240A(a)(2). Here, the Board explained that the phrase “lawfully admitted for permanent residence” does not refer to physical entry into the United States, but rather the acquisition of permanent resident status.

Board Applies New Precedent Outside of Fifth and Ninth Circuits: 27 I&N Dec. at 202

The Board explained that it was bound by the Fifth and Ninth Circuit precedents in cases arising in their jurisdiction because both circuits concluded that the language of section 240A(a)(2) is “unambiguous,” meaning that any contrary reading by the Board would not be entitled to deference. Accordingly, the Board held that it will only adhere to Tula-Rubio and Saldivar in cases arising in the Fifth and Ninth Circuits. However, in all other circuits, the Board will require that an alien have possessed some form of lawful immigration status at the time of admission to establish that they were “admitted in any status” under section 240A(a)(2) of the INA.

Before continuing, it is worth stepping away from the decision for a moment to examine the jurisdiction of the Fifth and Ninth Circuits.

The Fifth Circuit covers the following states in their entirety: Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

The Ninth Circuit covers the following states and territories in their entirety: Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington (State), Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Applying the Rule of the Ninth Circuit to the Respondent: 27 I&N Dec. at 202-203

Because the instant case arose in the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit, the Board was bound to apply the precedent from Saldivar v. Sessions.

Because the Board disagreed with the Immigration Judge that the respondent’s “wave through” entry did not constitute an admission, and because the Ninth Circuit held that a “wave through” entry can constitute admission “in any status,” the Board remanded the record to the Immigration Judge for further consideration of the respondent’s eligibility for cancellation of removal. The Board added that the respondent bore the burden of proving (1) that she was waved through at a port of entry in 1998, and (2) that she maintained continuous permanent residence for 7 years following that entry.

Concurring and Dissenting Opinion: 27 I&N Dec. at 203-206

The vast majority of BIA opinions are unanimous. However, in an uncommon occurrence, Board Member Roger A. Pauley authored an opinion concurring in judgment but dissenting in part. Although the Pauley concurring/dissenting opinion does not control, it is worth noting for the fact that there is disagreement within the Board on parts of the issue.

Pauley agreed with the majority that the Ninth Circuit opinion in Saldivar was binding in the instant case. His disagreement was due to the fact that he believed that the Fifth and Ninth Circuits reached the correct result on the issue, although he did not agree entirely with their reasoning. We discuss the Pauley opinion in more detail in a separate post [see article].

Conclusion

Matter of Castillo Angulo has the effect of creating two inconsistent rules for reading the phrase “admission in any status” in section 240A(a)(2) of the INA. Outside of the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, an alien must establish that at the time of admission, he or she must have possessed some form of lawful immigration status in order to start the clock on continuous residence for purpose of cancellation of removal under section 240A(a). Within the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, an alien need only establish that he or she was admitted in a procedurally regular matter to start the clock, and need not establish that he or she possessed lawful status at the time of a “wave through” entry.

Whether an alien will be able to meet the statutory requirements for cancellation of removal and subsequently establish that he or she merits relief will depend on the facts of a specific case. An alien in removal proceedings should always consult with an experienced immigration attorney for an individualized case evaluation and an examination of whether he or she may rebut the charges, or, otherwise establish eligibility for relief or protection from removal.