- Introduction

- Part I-A: Examining the Relevant Statutes

- Part I-B: Factual and Procedural History

- Part II: Jurisdictional Issues

- Part III: Analysis of the Applicability of the Canon of Constitutional Avoidance

- Part IV: Addressing the Dissent and the Meaning of “Detain”

- Part V: Remand to the Ninth Circuit for Consideration of Constitutional Arguments

- Part VI: Reversal

- Conclusion

Introduction

On February 27, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States decided an important immigration detention case, Jennings v. Rodriguez, 583 U.S. __ (2018) [PDF version].

The Supreme Court heard the case on appeal from the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Rodriguez v. Robbins, 804 F.3d 1060 (9th Cir. 2015) [PDF version]. The Ninth Circuit had held that aliens subject to mandatory detention under sections 235(b) and 236(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) could not be detained for longer than six months. It further held that aliens detained under section 236(a) were entitled to periodic individualized bond hearings every six months, and that an alien could only be detained beyond six months if the Government established by clear and convincing evidence that the alien is a flight risk or danger to the community. To reach this result, the Ninth Circuit applied what is called the “canon of constitutional avoidance,” which entails trying to solve the case on non-constitutional grounds if the statutes permit. Because the Ninth Circuit believed that a constitutional problem arose with indefinite detention, it construed sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c) as requiring periodic individual bond hearings and avoided reaching the constitutional questions.

In an opinion authored by Justice Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court reversed Rodriguez v. Robbins. Justice Alitio, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch, held that the Ninth Circuit misapplied the canon of constitutional avoidance. The majority noted that the canon of constitutional avoidance only applies when a statute has more than one plausible reading. The Court concluded that the Ninth Circuit’s reading of the detention provisions at issue was implausible. The Supreme Court majority did not reach the question of whether the detention provisions at issue where constitutional. Instead, it remanded the case to the Ninth Circuit for consideration of Rodriguez’s constitutional arguments in the first instance and also for consideration whether the Ninth Circuit had jurisdiction.

There were several separate opinions. First, Part II of Justice Alito’s opinion was only joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kennedy. In Part II of the opinion, Justice Alito concluded that the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to take the case. Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, concurred with Justice Alito’s opinion except for Part II. Justices Thomas and Gorsuch would have held that the Court did not have jurisdiction to hear the case under section 242(b)(9) of the INA, and would have vacated the judgment of the Ninth Circuit with instructions to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. However, because 6 of the Justices taking part in the case took the position that the Court had jurisdiction, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch joined in Justice Alito’s opinion on the merits. Justice Gorsuch did not, however, join footnote 6 of Justice Thomas’s concurring opinion. Justice Sonia Sotomayor joined only part III-C of the opinion of the Court, which dealt with bond hearings at the outset of detention. Justice Stephen Breyer authored the dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor.

In addition to the issues we noted, the various decisions explored interesting questions as to whether the case was properly brought as a class action lawsuit. We will explore the decision of the Court, the various opinions, and what the decision means going forward in three articles. This article will examine the opinion of the Court authored by Justice Samuel Alito. Please see our topic index on the case to learn more about the other opinions in the case and about what the effect of the decision is going forward.

Part I-A: Examining the Relevant Statutes

In Part I-A of the opinion of the Court, Justice Alito began by examining the relevant statutes at issue in Jennings v. Rodriguez. His opinion in this section was joined by four of his colleagues.

Detention of Applicants for Admission

Justice Alito explained that, in order to implement its immigration policy, the Government must be able to decide the following:

1. Who may enter the United States; and

2. Who may stay in the United States after entering.

When an alien arrives at the border or at a port of entry, the Government must decide whether the alien is admissible. Under section 235(a)(1), an alien who is present in the United States but has not been admitted or an alien who arrives at the border or at a port of entry without being admitted is considered to be an “applicant for admission.” Under section 235(a)(3), applicants for admission “shall be inspected by immigration officers.” Justice Alito explained that the purpose of this inspection is “to ensure that they may be admitted into the country consistent with U.S. immigration law.”

Justice Alito continued, explaining that applicants for admission under section 235(a)(1) fall under one of two categories. First, section 235(b)(1) covers aliens who are, as an initial matter, determined to be inadmissible for fraud, willful misrepresentation of a material facto, or lack of valid documentation (see section 235(b)(1)(A)(i)). Section 235(b)(1)(iii) allows the Attorney General to designate any applicant for admission who is not admitted or paroled and who fails to affirmatively show that he or she has been in the United States continuously for the previous two years for the same treatment as aliens described in section 235(b)(1)(i) and (ii). However, this provision is only applied to certain aliens encountered near the border who cannot establish their presence for the previous 14 days under current regulations and guidance. Section 235(b)(2) encompasses all applicants for admission who do not fall under section 235(b)(1).

Sections 235(b)(1) and 235(b)(2) both contain detention provisions.

An alien subject to section 235(b)(1) is normally ordered removed through the expedited removal process, as set forth in section 235(b)(1)(A)(i). However, if the alien indicates that he or she either intends to apply for asylum or otherwise has a fear of persecution, the alien will be referred for an asylum interview in accord with section 235(b)(1)(A)(ii). If the alien is determined to have a “credible fear of persecution,” he or she will not be removed. Instead, “the alien shall be detained for further consideration of the application for asylum” under section 235(b)(1)(B)(ii).

An alien who is described by section 235(b)(2) is subject to a different detention provision. Provided that an immigration officer “determines that an alien seeking admission is not clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to be admitted, the alien shall be detained for a proceeding under section 240 [of the INA].”Such an alien is then subject to continued detention pending the conclusion of regular section 240 removal proceedings.

Both detention provisions allow for a detained alien to be temporarily released on immigration parole under section 212(d)(5)(A) “for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” The implementing regulations for parole from detention in these scenarios are found in 8 C.F.R. 235.3. However, 8 C.F.R. 212(d)(5) makes clear that parole is not an admission. Thus, when the purpose of the alien’s parole has been served, 8 C.F.R. 235.3 requires that the alien be returned to the custody from which he or she was paroled and that “thereafter his case shall continue to be dealt with in the same manner as that of any other applicant for admission to the United States.”

Detention of Aliens in the United States Who Have Been Admitted or Paroled

Section 237 of the INA renders removable an alien who was inadmissible at the time of entry or who engages in certain conduct subsequent to admission [see index].

Section 236 of the INA contains provisions for the arrest and detention of aliens subject to section 237. Similarly to section 235, section 236 distinguishes between two different categories of aliens.

First, section 236(a) of the INA allows for the Attorney General to issue a warrant for the arrest and detention of an alien “pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed from the United States.” Under section 236(a)(2), the Attorney General may release the alien on bond or parole provided that the alien is not subject to mandatory detention under section 236(c).

Section 236(c) lists aliens who are subject to mandatory detention. Thus, it serves to limit the class of aliens who can be released on bond or parole under section 236(a)(2). Section 236(c)(1) requires the detention of aliens who are inadmissible or deportable on one of several criminal or terrorist-related grounds. Section 236(c)(2) allows for the Attorney General to release from detention an alien described in section 236(c)(1) only if he determines under 18 U.S.C. 3521 that the release of the alien “is necessary to provide protection to a witness, a potential witness, a person cooperating with an investigation into major criminal activity, or an immediate family member [of any of the listed individuals].” Furthermore, section 236(c)(2) requires the Attorney General to take into account the severity of the offense committed by the alien in making this determination.

Part I-B: Factual and Procedural History

In Part I-B, Justice Alito set forth the factual and procedural history of the case.

The respondent, Alejandro Rodriguez, was a native and citizen of Mexico. He had been a lawful permanent resident of the United States since 1987.

In 2004, Rodriguez was convicted of a drug offense and of theft of a vehicle. Based on these convictions, Rodriguez was charged as removable and detained under section 236 of the INA.

In removal proceedings, Rodriguez argued that he was not removable as charged, and that even if the immigration judge sustained the charges against him, he was eligible for relief from removal. In July of 2004, the immigration judge ordered Rodriguez removed to Mexico. On appeal, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) affirmed the immigration judge’s decision and dismissed Rodriguez’s appeal. Rodriguez then appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

While Rodriguez’s appeal was being litigated in the Ninth Circuit, he filed a separate habeas petition in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. There, Rodriguez argued that he was entitled to a bond hearing to determine whether his continued detention under section 236 of the INA was justified. Rodriguez’s case was consolidated with a similar case brought by Alejandro Garcia. Rodriguez and Garcia then moved together for class certification. The District Court denied the motion for class certification. However, the Ninth Circuit reversed the district court with regard to the denial of the motion for class certification in Rodriguez v. Hayes, 591 F.3d 1105, 1111 (9th Cir. 2010) [PDF version] (note that this is a separate issue from the appeal of the BIA decision). The Ninth Circuit held that the proposed class met the class certification requirements in Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Accordingly, it remanded the case to the District Court.

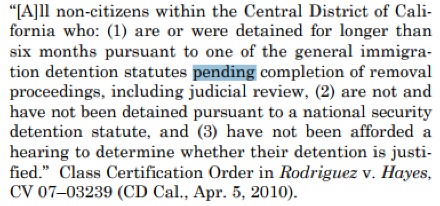

On remand, the District Court certified the following class:

Essentially, the District Court created a certified as a class aliens within its jurisdiction who were detained for longer than six months under a general detention provision pending the completion of removal proceedings (including review of a decision by a Federal court), who were not detained under a national security detention provision, and who were not given a bond hearing. The Court named Rodriguez as the class representative. It organized the newly-certified class into four subclasses based on four general detention statutes: sections 235(b), 236(a), 236(c), and 241(a) of the INA. Each of the four subclasses of aliens was certified to pursue declaratory and injunctive relief. In Rodriguez v. Robbins, 804 F.3d at 1074, 1085-86 (9th Cir. 2015), the Ninth Circuit held that the section 241(a) class was improperly certified, but it affirmed the certification of the other three classes, including Rodriguez’s.

In his complaint, Rodriguez (along with the other respondents) argued that sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c) do not authorize “prolonged” immigration detention without an individualized bond hearing at which the Government is required to establish by clear and convincing evidence that the detention of a class member remains justified. The respondents argued that, in the absence of the bond hearing requirement, sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c) violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. The respondents asked the District Court to require the Government to provide individualized bond hearings for all class members upon giving notice, and for the Government to be required at the hearing to justify the necessity for prolonged detention of class members by clear and convincing evidence that no other reasonable restrictions would ensure that the detainee would be present in the event of removal or by clear and convincing evidence that the detainee would pose a serious danger to the community.

Justice Alito explained that the permanent injunction granted by the District Court was “in line with the relief sought by respondents…”

In affirming the injunction, the Ninth Circuit relied on the canon of constitutional avoidance, though which the court construed the statute in such a manner as to avoid having to resolve the claim that the continued detention without a bond hearing was unconstitutional on due process grounds. The Ninth Circuit read sections 235(b) and 236(c) as imposing an implicit 6-month time limit on an alien’s detention, after which point the alien could only be detained if the requirements of section 236(a) were satisfied. The Ninth Circuit construed section 236(a) as requiring that an alien must be given a bond hearing every 6 months, and that he or she may only continue to be detained beyond the initial six-month period if the Government proves by clear and convincing evidence that further detention is justified. Rodriguez v. Robbins, 804 F.3d at 1085-87.

The Government appealed from the Ninth Circuit decision in Rodriguez v. Robbins. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

Part II: Jurisdictional Issues

Part II of the majority decision addressed whether the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to consider the claims of the respondents. However, this part of the opinion did not command a majority, and was accordingly not part of the opinion of the court. Justice Alito was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kennedy. However, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch, who otherwise joined in the majority opinion, disagreed, taking the position that the Supreme Court lacked jurisdiction to consider the claims of the respondents. Interestingly, the three Justices who dissented with the majority on the merits of the case nevertheless agreed with Justice Alito that the Supreme Court had jurisdiction, meaning that six of the eight Justices who considered the case agreed that the Court did have jurisdiction to hear the respondents’ claims. For this reason, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch concurred with the majority on the merits even though they would have preferred to not reach the merits. We will examine Justice Alito’s analysis of the jurisdictional issues and Justice Thomas’s different view in a separate article [see article].

Part III: Analysis of the Applicability of the Canon of Constitutional Avoidance

In Part III of the opinion of the court, Justice Alito, writing again for a five-Justice majority, rejected the Ninth Circuit’s decision based upon that court’s faulty and misplaced reliance on the canon of constitutional avoidance. The Ninth Circuit relied on the canon of constitutional avoidance to limit the Government’s detention authority under sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c).

Justice Alito began by explaining the canon. In Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22 (1932) [PDF version], the Supreme Court held that, when “serious doubt” whether a law is constitutional, “it is a cardinal principle that this Court will first ascertain whether a construction of the statute is fairly possible by which the question may be avoided.” In short, this means that if there is a serious constitutional challenge to a statute, the Supreme Court will first look to determine whether the statute can be fairly read in such a manner as to avoid having to address the constitutional issue. The Supreme Court will only address the constitutional question as a last resort if there is no fair way to read the statute to avoid the constitutional question.

In applying the canon, the Ninth Circuit took determined that the constitutional challenges to the detention statutes posed serious challenges, and determined that the statutes could be construed in such a manner as to avoid having to address the constitutional issue.

In prefacing his analysis, Justice Alito cited to Clark v. Martinez, 543 U.S. 371, 385 (2005) [PDF version], in explaining that the canon of constitutional avoidance is only applicable when “after the application of ordinary textual analysis, the statute is found to be susceptible to more than one construction.” Where the statute only has one plausible construction, the canon of constitutional avoidance is not applicable. In such a case, the Court must address the constitutional question.

For the forthcoming reasons, the majority found that the Ninth Circuit misapplied the canon of constitutional avoidance with regard to sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c), and that its resulting construction of all three provisions was impermissible.

Part III-A: Rejecting Respondents’ Reading of 235(b)

The respondents argued, and the Ninth Circuit agreed, that sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) of the INA contain an “implicit” 6-month limit on the length of detention. The Ninth Circuit held that once an alien has been detained for 6 months under these provisions, he or she may only continue to be detained in accordance with section 236(a), which provides for bond hearings under certain circumstances.

Justice Alito explained that the canon of constitutional avoidance “does not give a court the authority to rewrite a statute as it pleases.” Citing to Clark, at 381, he noted that the canon allows a Court to “choose between competing plausible interpretations of a statutory text.” Accordingly, in order for the respondents to prevail, Justice Alito stated that they had to establish that the statute could plausibly be read to contain an implicit 6-month limit.

Justice Alito found the respondents’ interpretation of sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) to be problematic on many levels, but primarily because “[n]othing in the text … even hints that those provisions restrict detention after six months…” He added that the respondents, and by effect the Ninth Circuit, “[did] not engage in any analysis of the text,” and he suggested that they appealed to the canon of constitutional avoidance in order to read the 6-month limitation into the text where it did not exist.

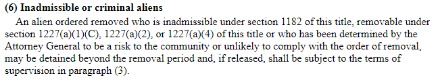

Instead, Justice Alito wrote, the Ninth Circuit “all but ignored the statutory text” and instead relied heavily upon the Supreme Court decision in Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001) [PDF version]. However, the issue in Zadvydas was a separate detention provision found in section 241(a)(6) of the INA providing for the detention of aliens who have already been ordered removed from the United States. Section 241(a)(1)(A), requires the Attorney General to complete the removal of an alien within a 90-day period, during which the alien must be detained in accord with section 241(a)(2). Section 241(a)(6), therefore, provides discretionary authority to detain certain aliens ordered removed beyond the 90-day period while efforts to remove the alien continue. For reference, please see the text of section 241(a)(6) below:

[Click image to view full size]

Justice Alito explained that the Court in Zadvydas invoked the canon of constitutional avoidance, upon first finding that section 241(a)(6) was ambiguous to the extent that it included the phrase “may be detained.” The Court read this as offering discretion to the Attorney General, but not unlimited discretion, and the Court construed section 241(a)(6) as precluding the detention of an alien beyond “a period reasonably necessary to secure removal,” and determined that a reasonable period was 6 months. Zadvydas, at 699, 701.1 In the event that an alien provided good reason to believe that it was unlikely he or she would be removed imminently, the Court held that “the Government must either rebut that showing or release the alien.” Id.

Justice Alito and the majority in the instant case recognized that “Zadvydas represents a notably generous application of the constitutional-avoidance canon…” However, he stated that the Ninth Circuit “went much further” The majority opinion criticized the Ninth Circuit for relying upon Zadvydas without proffering any analysis on whether the reasoning in that case could be fairly applied to the reasoning in Rodriguez. For reasons that we will examine, the majority in Rodriguez concluded that the statute at issue in Zadvydas was materially different from sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2).

First, Justice Alito noted that, unlike section 241(a)(6), sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) specify the length of detention. Section 235(b)(1) mandates detention “for further consideration of the application for asylum.” Under section 235(b)(1)(B)(ii), detention continues until immigration officers finish considering the asylum application. Section 235(b)(2) mandates detention “for a [removal] proceeding.” Under section 235(b)(2)(A), detention is to persist until the conclusion of removal proceedings. Justice Alito noted that sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) use the language “shall be detained,” which is the language of a requirement, not discretion. Recall that the Court in Zadvydas found that the phrase “may be detained,” implying discretion, was critical to the court’s finding that the statute was ambiguous.

Finally, Justice Alito noted that, unlike section 241(a)(6), section 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) explicitly state that the Attorney General may temporarily parole aliens subject to detention “for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” Justice Alito read this express exemption as strongly “impl[ying] that there are no other circumstances in which alien’s detained under [section 235(b)] may be released.” Accordingly, because the majority concluded that section 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) are not ambiguous as they set forth the parameters of detention, it concluded that the Court’s reasoning in Zadvydas, which relied on the finding of an apparent ambiguity of section 241(a)(6), was unpersuasive and unfounded.

Additionally, the respondents advanced a separate argument hinging on the meaning of the term “for” in sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2). Notably, this argument had not been advanced in the Ninth Circuit. The respondents noted that the term “for” appeared in both provisions and argued that it meant that detention was only mandated until the start of applicable proceedings but not thoughout or until the conclusion of the proceedings. The respondents noted that sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2) authorize detention “for” further proceedings, whereas section 235(b)(1)(B)(iii)(IV) authorizes detention “pending” a final determination on credible fear of persecution. The effect of this distinction, according to the respondents, was that the statutes requiring detention “for” further proceedings were distinguishable from the statute requiring detention “pending” final determination in that they only authorized detention until proceedings commenced.

However, Justice Alito rejected the respondents’ second argument as being “inconsistent with ordinary English usage and incompatible with the rest of the statute.” Citing to multiple dictionary definitions, Justice Alito explained that “for” can mean “during” or “throughout” and not only in preparation of. Accordingly, the majority found that the term “for” must be read in light of the statute as a whole. Additionally, Justice Alito noted other examples in the INA where “for” is rightly read as pertaining to an entire process, not only until the beginning of a process. He considered that under the respondents’ reading of section 235(b)(1), an alien could be detained without a warrant at the border until the commencement of proceedings, but after the proceedings began, the alien could only be detained with a warrant issued by the Attorney General under section 236(a). This, the majority held, “makes little sense.”

Part III-B: Rejecting Respondents’ Claims Regarding Section 236(c)

Justice Alito and the other four members of the majority also rejected the respondents’ claims and the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning regarding section 236(c). In fact, Justice Alito began by describing the language of section 236(c) as “even clearer” than the language of sections 235(b)(1) and (b)(2). Section 236(c)(1) gives the Attorney General discretion to issue a warrant for the detention of any alien pending removal proceedings who is not described in section 236(c)(3). Section 236(c)(3) sets forth mandatory detention provisions for certain aliens with one limited exception set forth in statute.

Justice Alito found that, like section 235(b), section 236(c) contains no facial limit to the length of detention it authorizes. Furthermore, by expressly stating circumstances under which an alien detained under the mandatory detention provision of section 236(c) can be released, the statute “reinforces the conclusion that aliens detained under its authority are not entitled to be released under any circumstances other than those expressly recognized by the statute.” Just Alito added that, together with section 236(a), section 236(c) “makes clear that detention of aliens within its scope must continue ‘pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed from the United States.”

The respondents made, and the Ninth Circuit accepted, a similar argument with regard to 236(a) that they made regarding section 235(b)(1) and (b)(2). Specifically, they took the position that section 236(c) should be construed as including an implicit 6-month limit on the length of mandatory detention. Justice Alito and the majority concluded that this reading fell “far short of a ‘plausible statutory construction.’”

The respondents argued that section 236(c) was silent as to the length of mandatory detention, and accordingly could not be construed as authorizing prolonged mandatory detention. They took the position that Congress would have used clearer terms to specif indeterminate detention, citing to Zadvydas. However, the majority found that section 236(c) was not “silent” on the matter at all, because it mandated detention “pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed from the United States,” and it prohibited release except for limited witness-protection purposes. Justice Alito expressly criticized the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning on this point, stating that “[t]he constitutional avoidance canon does not countenance such textual alchemy.”

Justice Alito noted that in Demore v. Kim, 538 U.S. 510, 529 [PDF version], the Supreme Court distinguished section 236(c) from the statute at issue in Zadvydas to the extent that section 236(c) has a “definite termination point.” For section 236(c), that point transpires with the conclusion of removal proceedings, and the majority found that this was the sole limitation on the mandatory detention authority under section 236(c).

The respondents argued that the explicit authorization for release from section 236(c) detention for witness-protection purposes did not imply that the statute did not allow for other forms of release. However, Justice Alito described this reading as “def[ying] the statutory text.” He noted that section 236(c)(2) — which provides for release for witness-protection reasons — states that an alien may be released “only if” its conditions are met. Accordingly, the majority read this as precluding release on other grounds.

The respondents advanced an additional claim, arguing that if the Court did not accept their reading of section 236(c), that statute would be rendered redundant in light of detention provisions under the PATRIOT Act applying to certain terrorist suspects. While the majority acknowledged that there is overlap between the detention provisions in section 236(c) and the PATRIOT Act. However, the provisions are not identical in scope. Section 236(c) not only covers aliens who are removable on specific terrorism-related grounds, but also aliens who are removable based on convictions for more common criminal offenses. Conversely, the PATRIOT Act covers aliens who pose threats to national security or who are engaged in any activity that endangers national security, which is broader than the national security provisions of section 236(c). Furthermore, the PATRIOT Act permits detention until an alien is removed, rather than until a decision is made on whether the alien is removable. For these reasons, the Court concluded that its reading of section 236(c) was not redundant in light of the PATRIOT Act mandatory detention provisions.

Part III-C: Detention Provision in Section 236(a)

Interestingly, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who otherwise dissented from the opinion of the court, joined the majority for Part III-C alone, meaning that six Justices agreed with this short part of the ruling.

The majority explained that under regulations in 8 C.F.R. 236.1(d)(1) and 1236.1(d)(1), an alien who is detained pending a decision on removal on the warrant of the Attorney General under section 236(a) is entitled to a bond hearing at the onset of detention. Furthermore, provided that the alien is not described by section 236(c), the Attorney General may grant bond or conditional parole.

Justice Alito noted that the Ninth Circuit’s decision ordered the Government to provide protections to aliens detained under section 236(a) that go well beyond anything required in the statute and regulations. Specifically, the Ninth Circuit required the Government to grant periodic bond hearings to such aliens every six months. In such bond hearings, the Ninth Circuit’s decision required the Attorney General to prove by clear and convincing evidence that the continued detention of the alien was necessary. The six-Justice majority held that the text of section 236(a) does not “even remotely” support these requirements. Furthermore, Justice Alito wrote, the statute also did not “even hint that the length of detention prior to a bond hearing must be specifically considered in determining whether an alien should be released.”

Part IV: Addressing the Dissent and the Meaning of “Detain”

Part IV of the majority opinion was devoted to challenging the dissent’s definition of the word “detain.” Justice Alito criticized the dissent for giving the term “detain” broad effect, applying it not only to aliens in immigration detention, but also to aliens who are released from detention subject to restrictions on their movement. We address the debate over the meaning and relevance of the terms “detain” and “custody” in our discussion of Justice Breyer’s dissenting opinion in which he explains why he would have upheld the Ninth Circuit decision [see article].

Part V: Remand to the Ninth Circuit for Consideration of Constitutional Arguments

Consistent with construing the relevant detention provisions after applying the canon of constitutional avoidance, the Ninth Circuit did not reach the merits of the respondents’ constitutional due process claims. Because the Supreme Court is a court of review, not a court of first view, the majority declined to consider the respondents’ constitutional arguments, instead remanding the case to the Ninth Circuit to consider them in the first instance.

However, before addressing the constitutional arguments, the Court instructed the Ninth Circuit to “reexamine whether respondents can continue litigating their claims as a class.” Justice Alito explained that when the District Court granted class certification, it had the respondents’ statutory interpretation claims in mind. Because the Supreme Court has resolved the statutory claims, this calls the District Court’s decision certifying the class into question.

First, the Court noted that section 242(f)(1) of the INA, no court other than the Supreme Court “shall have the authority to enjoin or restrain the operation of [sections 231-242 of the INA] other than with respect to the application of such provisions to an individual alien against whom proceedings under such part have been initiated.” In Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, 525 U.S. 471, 481 (1999) [PDF version], the Court held that section 242(f)(1) “prohibits federal courts from granting classwide injunctive relief against the operation of [sections 231-242].” Although the Ninth Circuit held that section 242(f)(1) did not prevent consideration of the respondents’ statutory interpretation claims, Justice Alito noted that the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning did not seem to apply to the constitutional claims. Accordingly, the Supreme Court directed the Ninth Circuit to consider whether it could issue class-wide injunctive relief based on the constitutional claims, and if not, whether the grant of injunctive relief could sustain the class on its own.

Furthermore, the Court also directed the Ninth Circuit to “consider whether a Rule 23(b)(2) class action continues to be the appropriate vehicle for respondents’ claims in light of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 564 U.S. 338 (2011) [PDF version]. In Dukes, the Court held that “Rule 23(b)(2) applies only when a single injunction or declaratory judgment would provide relief to each member of the class.” Id. at 360. The Court noted that this issue was relevant on remand because the Ninth Circuit itself acknowledged that some members of the class may not be entitled to bond hearings as a constitutional matter.

Finally, the majority directed the Ninth Circuit to consider whether Rule 23(b)(2) class action, litigated on common facts, is an appropriate vehicle for resolving the respondents’ Due Process claims. Justice Alito cited to Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 481 (1972) [PDF version], wherein the Court held that “[D]ue process is flexible” and that it “calls for such procedural protections as the particular situation demands.”

Part VI: Reversal

The five-Justice majority reversed the judgment of the Ninth Circuit and remanded the case for further proceedings consistent with its opinion.

Conclusion

Jennings v. Rodriguez is a highly significant decision that is very unfavorable to aliens detained under sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c). In addition to reversing the Ninth Circuit, the decision implicitly implicates similarly-reasoned precedents from other circuits, including the Second, Third, and Eleventh. It remains to be seen how the issue is litigated in light of Rodriguez.

However, it is important to note that the respondents will still have the opportunity to have their constitutional claims against the detention provisions considered by the Ninth Circuit. While one may reasonably question the prospects of a ruling in favor of the constitutional claims of the respondents prevailing with a majority of the Supreme Court, it is important to note that the Court remanded for consideration of those very claims.

For the time being, Rodriguez undercuts the legal rationales behind limiting detention under sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c). An alien who is detained under any provision, including the three in question in the instant case, should consult with an experienced immigration attorney as soon as possible. An experienced attorney will be able to assess the specific circumstances of an individual’s case and determine what forms of relief, if any, may be available to the alien both in the detention context and regarding his or her overall immigration situation.

Please see our topic index on the Rodriguez to learn about the other opinions in the case and updates on litigation on the issue.