- Introduction

- Before Reading

- Relevant Statute Involved in Jurisdiction Debate

- Concurring Opinion (Justice Thomas) Part II-A: Arguing that INA Precludes Judicial Review

- Plurality Opinion (Justice Alito) Part II: Arguing that Courts Have Jurisdiction

- A. Regarding Section 242(b)(9)

- B. Regarding Section 236(e)

- Dissenting Opinion (Justice Breyer) Part IV: Also Finding No Jurisdictional Bar

- Concurring Opinion (Justice Thomas) Part II-B: Responding to Plurality and Dissent

- 1. Response to Plurality

- 2. Response to Dissent

- 3. Addressing Arguments of Respondents

- Concurring Opinion (Justice Thomas) Part III: Addressing Whether Application of Jurisdictional Restrictions to Mandatory Detention Violates Suspension Clause

- Conclusion

Introduction

On February 27, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a significant immigration detention decision in Jennings v. Rodriguez, 583 U.S. __ (2018) [PDF version]. In Rodriguez, a 5-3 majority of the Supreme Court reversed the United States Court of Appeals of the Ninth Circuit decision in Rodriguez v. Robbins, 803 F.3d 1060 (9th Cir. 2015) [PDF version], which held that aliens subject to mandatory detention under sections 235(b) and 236(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) could not be detained for longer than six months under those provisions, and aliens detained under section 236(a) were entitled to periodic individualized bond hearings every six months where the burden would be on the government to establish by clear and convincing evidence that the continued detention was necessary. Notably, the Supreme Court, as had the Ninth Circuit, decided the case without reaching the constitutional claims that had been raised in the appeal.. Instead, it reversed the Ninth Circuit on the ground that its interpretation of the statutes was impermissible with respect to the statutory language.

In this article, we will examine the concurring opinion filed by Justice Clarence Thomas, in which he was joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch for all but footnote 6. Justices Thomas and Gorsuch took the position that section 242(b)(9) of the INA deprived the courts of jurisdiction to consider the respondents’ challenges to their immigration detention. For this reason, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch would have vacated the decision of the Ninth Circuit with instructions to dismiss the challenges due to lack of jurisdiction. However, because the other three members of the majority and the three dissenters in the case took the position that the Court did have jurisdiction, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch concurred with the majority on the merits, while noting their dissent on the jurisdictional point.

In this article, we will examine the debate over jurisdiction in Jennings v. Rodriguez. To do this, we will compare the positions of Justice Thomas’s concurrence, Justice Samuel Alito’s plurality opinion on jurisdiction, and Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissenting opinion. In assessing the opinions of Justice Alito and Justice Breyer, we will see the Court’s limited precedent on the issue of its jurisdiction to consider claims of aliens detained while immigration proceedings are pending. In addition, we will examine other non-jurisdictional aspects of the Thomas concurring opinion. Finally, we will examine other issues discussed in the concurrence that stemmed from the position of Justices Thomas and Gorsuch that the Court lacked jurisdiction.

Before Reading

Before reading this article, please see our article on the Opinion of the Court, which details the precedential apects of the decision [see article]. Specifically, please see our section on the factual and procedural history of Jennings v. Rodriguez [see section] and the relevant statutes [see section], which detail the background necessary to appreciate the issues under consideration by the Court. We incorporate the factual and procedural history into this article by reference.

Relevant Statute Involved in Jurisdiction Debate

The main question that we will examine in this article is whether section 242(b)(9) of the INA deprives the Supreme Court and the federal district and circuit courts of jurisdiction to consider the respondents’ claims challenging the length of their immigration detention. For reference, section 242(b)(9) reads as follows:

Judicial review of all questions of law and fact, including interpretation and application of constitutional and statutory provisions, arising from any action taken or proceeding brought to remove an alien from the United States under this subchapter [including [sections 235 and 236]] shall be available only in judicial review of a final order of removal under this section. Except as otherwise provided in this section, no court shall have jurisdiction, by habeas corpus under [28 U.S.C. 2241] or any other habeas corpus petition, by [28 U.S.C. 1361 or 1651], or any other provision of law (statutory or nonstatutory), to review such an order or such questions of law and fact.

Notably, the language of section 242(b)(9) explicitly extends to sections 235 and 236. Thus, the issue before the Ninth Circuit and the Supreme Court was whether section 242(b)(9) prohibits aliens from challenging the duration of their detention pending the conclusion of removal proceedings. The statute limits the scope of judicial review of any action “arising from” actions taken to remove an alien except when a court is reviewing a final order of removal. The only statutory exception is for situations “otherwise provided in [section 242].” In the instant case, the respondents sought to challenge their mandatory detention pending removal proceedings and not in the context of a review of a final order of removal.

As we will see, Justice Alito in his plurality opinion on jurisdiction and Justice Breyer in his dissenting opinion, each joined by two colleagues, took the position that section 242(b)(9) does not deprive the federal courts of jurisdiction over challenges to the length of detention pending removal. Justices Thomas and Gorsuch alone took the opposite view.

Concurring Opinion (Justice Thomas) Part II-A: Arguing that INA Precludes Judicial Review

Justice Thomas began by noting that the Government had not contended that the Court lacked jurisdiction over the respondent’s claim by virtue of section 242(b)(9). Likewise, the respondent had not claimed affirmatively that jurisdiction existed notwithstanding section 242(b)(9). However, citing to Arbaugh v. Y & H Corp., 546 U.S. 500, 514 (2006) [PDF version], Justice Thomas explained that the Supreme Court has an affirmative and “independent obligation” to assess whether it has jurisdiction.

Justice Thomas took the position that the language of section 242(b)(9) is “clear.” After parsing the statute, Justice Thomas concluded that section 242(b)(9) permits judicial review over “all questions of law and fact” “arising from an action taken or proceeding brought to remove an alien” solely and exclusively under the following two circumstances:

In connection with review of a final order of removal; or

Via a specific grant of jurisdiction in section 242.

Regarding the instant case, Justice Thomas further concluded that neither circumstance was presented: the respondents were not seeking review of a final order of removal, and the respondents did not cite to any specific grant of jurisdiction in section 242 that would allow for the Court to consider their claims. Accordingly, Justice Thomas explained, the section 242(b)(9) bar to review would not apply to the respondents’ claims only if those claims did not “aris[e] from any action or proceeding brought to remove an alien.”

Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Gorsuch, concluded that the respondents could not show that their claims did not arise from “any action or proceeding brought to remove” them. To this effect, Justice Thomas cited to the Supreme Court decision in Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, 525 U.S. 471, 482-83 (1999) [PDF version], which held that section 242(b)(9) is a “’general jurisdictional limitation’ that applies to ‘all claims arising from deportation proceedings’ and the ‘many … decisions or actions that may be a part of the deportation process.’” To that effect, Justice Thomas further cited to Demore v. Kim, 538 U.S. 510, 523 (2003) [PDF version], wherein the Court had stated that a detention pending removal proceeding is an “aspect of the deportation process.” In Demore, at 528, Justice Thomas noted, the Court discussed the purpose of detention pending proceedings, describing it as “preventing deportable criminal aliens from fleeing prior to or during their removal proceedings, thus increasing the chance that, if ordered removed, the aliens will be successfully removed.” He also cited to Carlson v. Landon, 342 U.S. 524, 528 (1952) [PDF version], wherein the Court had held that “[d]etention is necessarily a part of [the] deportation procedure.”

In light of the above, Justice Thomas construed the phrase “any action taken … to remove an alien from the United States” to necessarily cover, at a minimum, “congressionally authorized portions of the deportation process that necessarily serve the purpose of ensuring an alien’s removal.” Regarding the respondents’ claim, Justice Thomas’s reading of section 242(b)(9) necessarily covered “[c]laims challenging detention during removal proceedings…”

Plurality Opinion (Justice Alito): Part II: Arguing that Courts Have Jurisdiction

Justices Thomas and Gorsuch joined all parts of Justice Alito’s Opinion of the Court but for Part II, which addressed jurisdiction. Accordingly, Part II of Justice Alito’s opinion, joined only by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy, is not part of the Opinion of the Court. However, as we will see, the dissenters — Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor — agreed with the plurality opinion to the extent that it concluded that the Court did have jurisdiction to hear the respondents’ claims.

Interestingly, the plurality also discussed whether section 236(e) deprived the courts of jurisdiction, ultimately concluding that it did not. Justice Thomas only addressed section 236(e) in footnote six of his concurring opinion, and this was notably the only portion of his concurrence that was not joined by Justice Gorsuch.

A. Regarding Section 242(b)(9)

Contrary to the conclusion reached by Justice Thomas, Justices Alito, Roberts, and Kennedy concluded that section 242(b)(9) did not deny the Supreme Court of jurisdiction over the claims presented in the instant case. Justice Alito explained that the Supreme Court was called upon in the instant case to “decide ‘questions of law,’ specifically, whether, contrary to the decision of the [Ninth Circuit], certain statutory provisions require detention without a bond hearing.”

Justice Alito began by acknowledging that one could argue that the respondents’ claims “arose” from actions taken to remove them, for if they were not subject to removal, they would not have been detained. However, Justice Alito then urged that “this expansive interpretation of [section 242(b)(9)] would lead to staggering results.”

For example, he assumed, for the sake of argument, that all of the claims of the class members in the instant case were “arising from” any action taken to remove them. As a result, he proposed that judicial review may not then be available for claims of alleged official misconduct during the detention, such as a claim under Bivens v. Six Unknown Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (1971) [PDF version], unless the alien were seeking review of a final order of removal Please see our issue on a Bivens claim also noted by Justice Alito in Ziglar v. Abbasi, 137 S.Ct. 1843 (2017) [PDF version] [see article].

Furthermore, Justice Alito noted that, regarding prolonged detention claims, reading “arising from” broadly would have the effect of precluding all judicial review outside of the context of and prior to a review of a final order. He concluded that this would lead to two “absurd results.” First, if the alien had been issued a final order of removal, he or she would have already been subjected to prolonged detention without having had the opportunity to seek review. Second, in the event that the alien was never issued a final order of removal, he or she would have no opportunity to seek judicial review of his or her claim of prolonged detention.

Citing to Gobeille v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 136 S.Ct. 936 (2016) [PDF version], Justice Alito stated that “when confronted with capricious phrases like ‘arising from,’ ‘we have eschewed ‘uncritical literalism” leading to results that ‘no sensible person could have intended.’” Here, Justice Alito cited to a long list of decisions to support his argument. He made special note of the Court’s decision in Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Comm., 525 U.S. 471, 482-83 (1999), addressing section 242(g) of the INA, which denies jurisdiction to courts “to hear any cause or claim by or on behalf of any alien arising from the decision or action by the Attorney General to commence proceedings, adjudicate cases, or execute removal orders against any alien under this chapter.” Regarding this decision, Justice Alito stated that “[w]e did not interpret this language to sweep in any claim that can technically be said to ‘arise from’ the three listed actions of the Attorney General. Instead, we read the language to refer to just those three specific actions themselves.”

Justice Alito did not find it necessary to provide a comprehensive interpretation of section 242(b)(9), and noted that neither party had addressed the scope of the provision. He stated that “[f]or present purposes, it is enough to note that respondents are not asking for review of an order of removal; they are not challenging the decision to detain them in the first place or to seek removal; and they are not even challenging any part of the process by which their removability will be determined.”

In footnote 3, Justice Alito addressed the claim in the concurring opinion that detention pending proceedings “is an ‘action taken … to remove’ an alien.” Justice Alito stated that, even if one assumes for the sake of argument that detention in this context is an action taken to remove an alien, rather than to prevent an alien from fleeing or committing a crime while proceedings are pending, it would not affect the question of jurisdiction. This is because, Justice Alito explained, “[t]he question is not whether detention is an action taken to remove an alien but whether the legal questions in this case arise from such an action.” For the foregoing reasons, Justice Alito concluded that the legal questions in Rodriguez were too remote to be covered by section 242(b)(9).

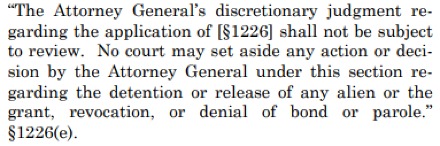

B. Regarding Section 236(e)

As we noted, Justice Thomas’ concurring opinion did not discuss section 236(e) outside of a single footnote. Here, we will examine Justice Alito’s brief analysis of section 236(e)’s effect on jurisdiction.

Section 236(e) reads as follows:

Justice Alito relied upon the Court’s decision in Demore v. Kim, 538 U.S. 510, 516 (2003) [PDF version], which Justice Alito noted held that section 236(e) precludes an alien from “challeng[ing] a ‘discretionary judgment’ by the Attorney General or a ‘decision’ that the Attorney General has made regarding his detention or release.” However, the Court further held that section 236(e) does not preclude “challenges [to] the statutory framework that permits [the alien’s] detention without bail.” Justice Alito concluded that the respondents’ challenge in the instant case fell under the latter category because they addressed the Government’s detention authority under section 236 as a whole under the Fifth Amendment. Accordingly, Justice Alito would have reached the merits of the respondents’ claims.

Dissenting Opinion (Justice Breyer): Also Finding No Jurisdictional Bar

The three dissenters — Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, and Sotomayor — agreed with the plurality that the Court had jurisdiction.

Regarding section 242(b)(9), Justice Breyer wrote the following: “Jurisdiction is also unaffected by [section 242(b)(9)], which by its terms applies only ‘[w]ith respect to review of an order of removal under [section 242(a)(1)].” Respondents challenge their detention without bail, not an order of removal.”

Concurring Opinion (Justice Thomas) Part II-B: Responding to Plurality and Dissent

In Part II-B of the concurring opinion, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch responded to the positions of the plurality and dissenting opinions regarding jurisdiction. Furthermore, they also addressed the position taken by the respondents at oral argument. We will examine each of these parts of the concurring opinion in the following subsections.

1. Response to the Plurality

Justice Thomas responded to the claim of the plurality that section 242(b)(9) would only foreclose review of the respondents’ claims if the provision was given an “expansive interpretation” by stating that even under a narrow reading the statute would still preclude review of the respondents’ claims. How so? Justice Thomas explained that because detention of an alien constitutes an “action taken … to remove” that alien, even the narrowest reading of section 242(b)(9) would cover and thus bar review of claims brought to challenge the duration of detention pending proceedings.

Justice Thomas found the plurality’s reliance on Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee to be unavailing. Citing to that decision at 482-83, Justice Thomas noted that the Court had held that section 242(b)(9) “covers ‘all claims arising from deportation proceedings’ and the ‘many … decisions or actions that may be part of the deportation process.’” Among the claims that would be covered, the Court specifically included challenges to a decision to open an investigation or challenges to a decision to surveil a suspected violator of the immigration laws. Justice Thomas stated that “[i]f surveilling a suspected violator falls under the statute, then the detention of a known violator certainly does as well.”

Justice Thomas also rejected the plurality’s contention that his “expansive interpretation” of section 242(b)(9) would lead to “staggering results.” Referencing the plurality’s claim that this interpretation would preclude the bringing of “lawsuits challenging inhumane conditions of confinement, assaults, and negligent driving,” Justice Thomas stated that “those actions are neither congressionally authorized nor meant to ensure that an alien can be removed.” Accordingly, Justice Thomas reasoned that his conclusion that section 242(b)(9) “covers an alien’s challenge to the fact of his detention” does not extend to “actions that go beyond the Government’s lawful pursuit of its removal objective.”

2. Response to Dissent

Justice Thomas interpreted the position of the dissent as “read[ing] the prefatory clause [of section 242(b)(9) to apply] only to ‘a challenge [to] an order of removal.’” Justice Thomas disagreed with this restrictive reading as well.

Justice Thomas assessed that section 242(b)(9) covers “all questions of law and fact” that arise from removal. Furthermore, the statute unequivocally “specifies that [section 242(a)(1)] provides the only means for reviewing ‘such an order or such questions of law or fact.’” After noting that “or” almost always signifies a disjunctive, Justice Thomas stated that “[b]y interpreting [section 242(b)(9)] as governing only removal orders, the dissent reads ‘or such questions of law or fact’ out of the statute.” He added that this reading would also render section 242(a)(5) superfluous (t section 242(a)(1) encompasses the sole ground for review of an order of removal). Citing to Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Council, at 483, Justice Thomas noted that the Court “typically disfavors such interpretations.”

Justice Thomas further reiterated his conclusion that “the prefatory clause plainly does not change the scope of [section 242(b)(9)], which covers ‘all questions of law or fact’ arising from the removal process.

3. Addressing Arguments of Respondents

In oral arguments, the respondents had taken the position that if section 242(b)(9) barred judicial review of their claims, then they and similarly situated individuals would be denied the opportunity to obtain review of claims regarding the length of detention during proceedings until after that detention had already ended. .

Justice Thomas found this argument to be “unpersuasive and foreclosed by precedent.” First, Justice Thomas explained that “[t]he Constitution does not guarantee litigants the most effective means of judicial review for every type of claim they want to raise.” For example, he cited to Heikkila v. Barber, 345 U.S. 229, 237 (1953) [PDF version], wherein the Court upheld limitations on judicial review of deportation “despite [the] apparent inconvenience to the alien.”

Furthermore, Justice Thomas read Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee as raising “essentially the same argument” as that made by respondents in oral arguments. In that case at pp, 487-92, the Court rejected an argument that a similar provision in section 242(g) should not be construed as barring First Amendment claims of selective enforcement outside of the context of a review of a final order of removal. There, the Court held that “an alien unlawfully in this country has no constitutional right to assert selective enforcement as a defense against his deportation.” The Court suggested that it had a duty to abide by the restrictions on judicial review except in “a rare case in which the alleged basis of discrimination is so outrageous that the foregoing considerations could be overcome.”

Accordingly, Justice Thomas concluded that the respondents’ argument that section 242(b)(9) should not be read to preclude meaningful judicial review could not overcome the limitations on judicial review clearly imposed by Congress in the statute. Justice Thomas noted that the Court had repeatedly upheld detention during proceedings as constitutional. Furthermore, he added that the claims of the respondents simply did not qualify as the “rare case in which the alleged [executive action] is so outrageous” such that it could overcome the statutory limits on judicial review.

Following this reasoning, Justice Thomas would have held that the respondents could only raise claims against their detention in petitions for review of their final orders of removal.

Footnote 6

Justice Gorsuch joined every part of Justice Thomas’s concurring opinion but for footnote 6, in which. Justice Thomas did not take a position on whether some of the respondents may face other jurisdictional hurdles in addition to those discussed in the concurring opinion. Justice Thomas stated that he continued to agree with the concurring opinion of former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in Demore v. Kim, at 533, wherein she stated that section 236(e) “unequivocally deprives federal courts of jurisdiction to set aside ‘any action or decision’ by the Attorney General regarding detention.”

Concurring Opinion (Justice Thomas) Part III: Addressing Whether Application of Jurisdictional Restrictions to Mandatory Detention Violates Suspension Clause

In Part III of his concurring opinion, Justice Thomas addressed whether reading section 242(b)(9) as a bar to the respondents claims would violate the Suspension Clause of the United States Constitution. Justice Thomas’s concurring opinion was the only opinion to address this issue. This is because the issue is only relevant if section 242(b)(9) is read as barring the respondents claims.

The Suspension Clause, found in clause 2 of section 9 of Article I of the Constitution, reads as follows:

The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.1

Justice Thomas held that, even if one assumed that the Suspension Clause barred Congress from stripping habeas jurisdiction over the detention claims brought by the respondent, the instant case did not involve a habeas petition. (Note: Justice Thomas cited to the dissenting opinion of Justice Antonin Scalia, in which he joined, in I.N.S. v. St. Cyr, 533 U.S. 289, at 337-346 (Scalia, J., dissenting), wherein they argued that a separate jurisdiction-stripping provision precluded the Court from considering a habeas petition).

Justice Thomas explained that the respondents did not seek habeas relief, noting that their complaint, among other things, did not request that the District Court issue a writ of habeas corpus. Instead, the respondents sought a declaration and injunction that would provide relief to present and future class members. Justice Thomas added that they had obtained class certification under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(2).

Justice Thomas continued by explaining that the respondents did not, in fact, obtain habeas relief from the lower court. Instead, they obtained a permanent classwide injunction. Citing to a description of a writ of habeas corpus in United States v. Jung Ah Lung, 124 U.S. 621, 622 (1888) [PDF version], Justice Thomas noted that the classwide injunction “looks nothing like a typical writ” in style or form. Furthermore, Justice Thomas highlighted that the injunction was directed at the Director for the Executive Office of Immigration Review rather than at a custodian at the detention facilities where the respondents were being held, as would be the case in a habeas proceeding. Furthermore, Justice Thomas cited to numerous examples of instances in which immigration law distinguishes between declaratory and injunctive relief and habeas relief. For example, in Heikkila, 345 U.S., at 230, the Court distinguished habeas relief from “injunctions, declaratory judgments, and other types of relief…” In St Cyr, 533 U.S. at 309-10, the Court noted that Congress in 1961 had stripped District Co