- Introduction

- Statutory Language

- USCIS Guidance

- Important Cases

- Additional Issue in Naturalization Context: Good Moral Character

- Conclusion

Introduction

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) contains nearly identically-worded inadmissibility and deportability provisions for unlawful voters. The inadmissibility provision is found in section 212(a)(10)(D) of the INA, and the deportability provision is found in section 237(a)(6). In both, aliens who violate a law relating to unlawful voting are covered. Each provide for a limited exception for certain aliens who voted unlawfully, but who had permanently resided in the United States prior to attaining the age of 16, had U.S. citizen parents, and who reasonably believed at the time of the violation that he or she was a U.S. citizen.

In this article, we will examine the immigration penalties for unlawful voting and when these provisions apply. To learn about the somewhat similar inadmissibility and deportability provisions for false claims to U.S. citizenship, please see our index article [see index].

Finally, this article is one of a series of articles on the section 237 deportability provisions. To see the other entries in our series, please consult the following list:

Inadmissible at Time of Entry or of Adjustment of Status or Violates Status [see article]

General Crimes [see article]

Failure to Register and Falsification of Documents [see article]

Security and Related Grounds [see article]

Public Charge [see article]

Statutory Language

Section 212(a)(10)(D) renders inadmissible an alien who engages in unlawful voting, whereas section 237(a)(6) renders such an alien deportable. An alien may be found to be inadmissible if he or she has not been admitted to the United States, whereas deportability provisions apply to aliens who are “in and admitted to the United States.”

Sections 212(a)(10)(D)(i) and 237(a)(6)(i) apply to “[a]ny alien who has voted in violation of any Federal, State, or local constitutional provision, statute, ordinance, or regulation…”

Whether the alien is found to be inadmissible or deportable will depend, as we noted, on his or her immigration status. However, sections 212(a)(10)(D)(i) and 237(a)(6)(i) cover otherwise identical conduct. Under both sections, the alien’s unlawful voting must have violated a “Federal, State, or local constitutional provision, statute, ordinance, or regulation…

The inadmissibility and deportability grounds provide for identical exceptions at sections 212(a)(10)(D)(ii) and 237(a)(6)(ii), respectively. The exceptions read as follows:

In the case of an alien who voted in a Federal, State, or local election (including an initiative, recall, or referendum) in violation of a lawful restriction of voting to citizens, if each natural parent of the alien (or, in the case of an adopted alien, each adoptive parent of the alien) is or was a citizen (whether by birth or naturalization), the alien permanently resided in the United States prior to attaining the age of 16, and the alien reasonably believed at the time of such violation that he or she was a citizen, the alien shall not be considered to be [inadmissible under section 212(a)(10)(D)(ii) or deportable under 237(a)(6)(iii)] based on such violation.

To put it succinctly, the exception applies in the following circumstance:

The alien voted unlawfully as defined in sections 212(a)(10)(D)(i) and 237(a)(6)(i);

Each natural parent (or adoptive parent) of the alien is or was a U.S. citizen;

The alien permanently resided in the United States prior to attaining the age of 16; and

The alien reasonably believed at the time of his or her unlawful voting that he or she was a U.S. citizen.

The exception to the unlawful voting grounds of inadmissibility and deportability is quite limited. The alien must satisfy each of the four requirements in order to not be subject to inadmissibility or deportability. Even if the alien meets the residency requirement and his or her parents are or were U.S. citizens, the alien still has the burden of establishing that he or she reasonably believed at the time he or she voted unlawfully that he or she was a U.S. citizen.

The separate and distinct inadmissibility (section 212(a)(6)(C)(ii)) and deportability (section 237(a)(3)(D)) provisions for false claims to U.S. citizenship contain a nearly identical exception. Please see the relevant section of our article on that subject for more information [see article].

USCIS Guidance

A legacy Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Memorandum issued on May 7, 2002, titled “Procedures for Handling Naturalization Applications of Aliens Who Voted Unlawfully or Falsely Represented Themselves as U.S. Citizens by Voting or Registering to Vote” outlined guidance for interpreting the unlawful voter provisions of the INA [PDF version]. As the title indicates, the memo addressed unlawful voters in the context of naturalization applications. However, its adjudicative principles apply more broadly. We will analyze the relevant points of the memo below.

Sections 212(a)(10)(D)(i) and 237(a)(6)(A) were added to the INA as part of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). The limited exceptions were added as part of the Child Citizenship Act of 2000 (CCA).

Here, it is important to note that the unlawful voting provision covers unlawful voting that occurred prior to the effective date of the provisions, which was September 30, 1996. Accordingly, any unlawful votes before, on, or after September 30, 1996, may trigger inadmissibility or deportability provided that the statutory requirements are met.

The IIRIRA did not only change the INA by adding provisions for unlawful voting, but also the criminal statutes. It added 18 U.S.C. 611, which reads as follows today:

[Click image to view full size]

An inadmissibility or deportability charge may be based on a criminal conviction in violation of 18 U.S.C. 611(a) (or a relevant State law on the issue). However, the memo makes clear that “[a]n alien who votes illegally but who has not been convicted under 18 U.S.C. 611 is still potentially removable.” This is because “[r]emoval charges can be sustained simply by proving that the alien voted in violation of the relevant law.” See our section on relevant cases for examples of situations in which an alien was found to be removable for unlawful voting for having violated 18 U.S.C. 611 without having been criminally convicted.

The memo, however, notes that in order for an applicant to be inadmissible or removable under one of the unlawful voting provisions, the conduct must be such that it “would be deemed unlawful under the relevant Federa, state, or local election law.” If the conduct would not be deemed unlawful under such a law, the alien would not be inadmissible or deportable for unlawful voting. In this sense, the unlawful voting provisions is narrower than the false claim to U.S. citizenship provisions, which do not require that the alien have violated an underlying Federal, state, or local law.

The memo provided adjudicative guidance for officers of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS). Here, the memo explained that “in most instances there will not be a conviction under 18 U.S.C. 1611…”

In making an unlawful voter inquiry, USCIS officers are instructed to determine if the individual:

a. Actually voted in violation of the relevant election law; or

b. Made a false claim to U.S. citizenship when registering to vote or voting in any Federal, State, or local election any time on or after September 30, 1996.

If either of the above scenarios occurred, the alien would be removable (or inadmissible). It is, of course, possible that an alien could be removable for both unlawful voting and for making a false claim to U.S. citizenship, although only one need be proven to sustain removability charges. If the individual does not qualify for the limited exception to deportability (U.S. citizen parents and having permanently resided in the United States since turning 16), the USCIS may consider “whether the [alien’s] case merits the exercise of prosecutorial discretion” (note: prosecutorial discretion consideration would most likely arise in naturalization cases).

The memo noted that a determination whether an alien voted in violation of a Federal, state, or local law “depends upon whether he or she: (1) actually voted and (2) the act of voting violated a specific election law provision.” Here, the memo explained that different election statutes may be worded differently. For example, while 18 U.S.C. 611 does not contain an intent requirement, other illegal voting provisions “may include a specific intent requirement.” For this reason, the memo stated that “the act of voting, by itself, is not sufficient to establish that the applicant voted unlawfully…” without reference to a specific “violation under the relevant election law.”

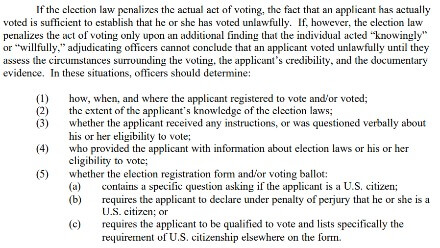

For example, the memo stated the following about election laws that penalize unlawfully voting “knowingly” or “willingly”:

[Click image to view full size]

In short, and as we will see in the next section on specific cases, situations involving unlawful voting in Federal elections (as defined by 18 U.S.C. 611) may be relatively straightforward. 18 U.S.C. 611 prohibits aliens from voting in elections with candidates for Federal office on the ballot. There is no requirement that the unlawful voting must be “knowing” or “willful.” Furthermore, the exception to 18 U.S.C. 611 is relatively limited. However, if inadmissibility or removability charges are based, instead, on state or local statutes, the issue may be more complicated depending on the specific language of the statute in question.

Important Cases

The Board issued one significant published decision on the unlawful voting deportability provision in Matter of Fitzpatrick, 26 I&N Dec. 559 (BIA 2015) [PDF version]. Before continuing, please note that we discuss Matter of Fitzpatrick in detail in a full article [see article].

In Matter of Fitzpatrick, the Board held that an alien who votes in an election involving candidates for Federal office in violation of 18 U.S.C. 611(a) is removable under section 237(a)(6)(A) of the INA. The Board found that 18 U.S.C. 611(a) is a “general intent” rather than a “specific intent” statute. Therefore, the alien at issue would have been removable “regardless of whether the alien knew that he or she was committing an unlawful act by voting.” Id. at 560-61.

Matter of Fitzpatrick followed the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Kimani v. Holder, 695 F.3d 666 (7th Cir. 2012) [PDF version], which addressed the same issues except in the inadmissibility context. The Seventh Circuit explained that “[a] statute that does not mention any mental-state (mens rea) requirement is a general-intent law.” Id. at 669. This means, that 18 U.S.C. 611 does not require that the individual who votes unlawfully knew or intended to violate the statute by voting with the knowledge that he or she could not do so lawfully. Instead, the statute requires only proof that the individual intended to vote and did vote. The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit reached the same conclusion in an appeal from a criminal conviction for violation 18 U.S.C. 611(a) in U.S. v. Knight, 490 F.3d 1268 (11th Cir. 2007) [PDF version].

In 2005, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued an interesting published decision in McDonald v. Gonzales, 400 F.3d 684 (9th Cir. 2005) [PDF version]. Unlike the first two cases involving 18 U.S.C. 611 that we discussed„ McDonald involved a Hawaii statute (H.R.S. 19-3.5(2)). The Hawaii statute reads in pertinent part as follows: “Any person who knowingly votes when the person is not entitled to vote” is guilty of a felony. Id. at 687. After analyzing the term “knowingly” in the context of Hawaii law, and applying the definition to the facts of the case, the Ninth Circuit concluded that it requires proof that the person actually knew that he or she dould not lawfully vote, but that “the mental state the IJ found might qualify as ‘should have known,’ or possibly as negligence, but it is not knowingness.” Id. at 689.

In Kimani, the Seventh Circuit distinguished the issue in McDonald from the issue involving 18 U.S.C. 611(a). The Seventh Circuit noted that “[t]he statute in McDonald is worded differently from [18 U.S.C.] 611(a).” 695 F.3d at 669. Although the Seventh Circuit stated that it was “skeptical” of the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning in McDonald, it “reserve[d] decision” on the issue. Id. at 669-70. In Matter of Fitzpatrick, the Board followed Kimani and found that the McDonald decision did not apply to immigration charges based on the language of 18 U.S.C. 611(a). 26 I&N Dec. at 561 n.4.

Additional Issue in Naturalization Context: Good Moral Character

In the USCIS Policy Manual (PM) at 12 USCIS-PM F.5(M)(1), the PM explains that a conviction for unlawful voting is unlikely to be a crime involving moral turpitude (CIMT) and does not, by itself, constitute a bar to good moral character. However, if an individual is incarcerated as a result of a conviction for unlawful voting for 180 days or more or if it is one of multiple convictions resulting in a sentence of 5 years or more in the aggregate, it will constitute a bar to good moral character. However, it is important to note that a false claim to U.S. citizenship is a CIMT and will constitute a bar to good moral character.

Conclusion

Unlawful voting carries significant consequences in immigration law, whether the alien is found to be inadmissible or deportable. Aliens are categorically prohibited under Federal law from voting in elections for Federal offices. Aliens in certain jurisdictions may be authorized to vote in certain local elections, consistent with applicable state and/or local laws. Even in cases where an alien may be authorized to vote, he or she should carefully study and follow any applicable requirements, and seek case-specific guidance if there is any uncertainty. It is important to note that falsely representing oneself to be a U.S. citizen, whether in order to vote or for other purposes, will always render an alien subject to the inadmissibility and/or deportability provisions on the subject in the INA.

An alien who is charged with inadmissibility or removability for unlawful voting or any other ground should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately for case-specific guidance.