- Introduction

- Derivation of Citizenship at Birth By Persons Born in the United States

- Acquisition of Citizenship Abroad at Birth Through One or Two U.S. Citizen Parent(s)

- Key Concept: Biological or Blood Relationship Between Parents and Child (non-309(a) cases)

- Key Concept: Residence Requirement When Both Parents of Child Born Abroad are U.S. Citizens

- Key Concept: Physical Presence Requirement for Certain U.S. Citizen Parents of Child Born Abroad

- Key Concept: Illustrating the Difference Between Residence and Physical Presence

- Key Concept: Former Retention Requirements

- Child of Two U.S. Citizen Parents (Married)

- Child of One U.S. Citizen Parent and One Noncitizen National Parent (Married)

- Child of one U.S. Citizen Parent and One Alien Parent (Married)

- Child Born Abroad of U.S. Citizen Mother and U.S. Citizen Father (Unmarried)

- Deriving Citizenship Through U.S. Citizen Father (Unmarried)

- Deriving Citizenship Through U.S. Citizen Mother (Unmarried)

- Child of U.S. Citizen Parent and Noncitizen National Parent (Unmarried)

- Special Case: Assisted Reproductive Technology

- Special Case: Posthumous Children

- Obtaining a Certificate of Citizenship

- Conclusion

Introduction

With the limited exception of children of diplomats, all children born in the United States — including certain U.S. territories — acquire U.S. citizenship and nationality at birth. Under certain circumstances, the child of one or two U.S. citizens may acquire citizenship at birth when born abroad. In this article, we will examine the current rules for deriving U.S. citizenship at birth. This article is updated to reflect the Supreme Court of the United States’ important decision in Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 137 S.Ct. 1678 (2017) [PDF version], wherein the Court invalidated certain statutory provisions making it easier for a U.S. citizen mother to pass U.S. citizenship to a child than a U.S. citizen father. We discuss Morales-Santana in detail in a separate article [see article].

Our article will generally follow the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) Policy Manual (PM) guidance and the U.S Department of State’s (DOS’s) Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) guidance on the subject. You can read the relevant section of the USCIS-PM — 12 USCIS-PM H.3 [PDF version] — to follow along with our article.

Derivation of Citizenship at Birth By Persons Born in the United States

Most people who derive citizenship and nationality at birth do so through birth in the United States. While we discuss this in detail in a separate article [see article], it is worth providing a general overview of the derivation of citizenship through birth in the United States before examining how citizenship can be derived from birth outside the United States.

Under section 301(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), a person who is born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States is a U.S. citizen and national from birth. Section 301(b) makes clear that this includes persons who are members of an Indian, Eskimo, Aleutian, or other Aboriginal tribe. With the limited exception of the children of certain diplomats, it extends to all persons born in the United States regardless of the immigration status, or lack thereof, of their parents.

INA 301(a) derives from the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In the pertinent part, Section 1 of Amendment XIV reads: “All persons born and naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” The Supreme Court has held that the Citizenship Clause, at the very least, guarantees that the child of a permanent residents is a U.S. citizen from birth. United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898) [PDF version].

Under 8 CFR 215.1(e), the term “United States” does not mean only the fifty States and the District of Columbia, but also Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, Swains Island, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Thus, individuals born today in those territories automatically derive citizenship from birth, with the same limited exception for diplomats. It is worth noting that individuals born in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands derive citizenship only through statute, and not under the Constitution, although this distinction is not significant for practical purposes. American Samoa is notably missing from the list of territories in 8 CFR 215.1(e). Persons born in American Samoa automatically derive U.S. nationality, but not U.S. citizenship, at birth, under similar rules to how persons born elsewhere in the United States derive citizenship and nationality (this applies to persons born in Swains Island as well). As we will examine, individuals born in American Samoa may instead derive citizenship if one or both parents are U.S. citizens, subject to limited exceptions. All U.S. citizens are U.S. nationals, and only a small subset of U.S. nationals (generally those born in American Samoa) are not U.S. citizens. Thus, the distinction between U.S. citizenship and nationality only has practical significance for a very small number of people.

The primary exception to deriving citizenship at birth applies to the children of diplomats who are considered to not be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. 8 CFR 101.3 defines the limited class of persons considered to not be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. 8 CFR 101.3(a) provides that “[a] person born in the United States to a foreign diplomatic officer accredited to the United States, as a matter of international law, is not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. That person is not a citizen under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Such a person may be considered a lawful permanent resident at birth.” The term “foreign diplomatic officer” is, however, limited to “a person listed in the State Department Diplomatic List, also known as the Blue List” under 8 CFR 101.3(a)(2). Children born to persons who do not fall within the scope of 8 FR 101.3(a)(2) do derive citizenship at birth in the United States, as clarified in 8 CFR 101.3(b). We discuss this limited exception in more detail in a separate article [see article].

In general, nearly every person who is born in the United States or in one of its territories — with the primary exception of American Samoa — will be a citizen from birth, whether through the Constitution, statute, or both. This applies regardless of immigration status, except for limited cases involving diplomats.

Acquisition of Citizenship Abroad at Birth Through One or Two U.S. Citizen Parent(s)

In certain cases, a child born abroad to one or two U.S. citizen parents may derive citizenship from birth through section 301 of the INA. The DOS explains that “[a]cquisition of U.S. citizenship by birth abroad to a U.S. citizen parent is governed by Federal statutes.” 8 FAM 301.4-1(A)(1). A person who derives citizenship at birth under statute is accorded all the rights and privileges of citizenship, and is not considered a naturalized citizen. 8 FAM 301.4-1(F)(1)-(2). The laws governing derivation of citizenship at birth for children born abroad have evolved over years — and whether one derived citizenship at birth depends on the facts of the particular case and the derivation of citizenship laws in effect at the time of the birth, including judicial precedents.

Below, we will first examine key concepts to understanding the derivation of citizenship rules and then examine the derivation of citizenship rules for various scenarios.

Key Concept: Biological or Blood Relationship Between Parents and Child (non-309(a) cases)

The transmitting parent must have a biological or blood relationship with the child. 8 FAM 301.4-1(D)(1). For all cases other than those governed by INA 309(a) (derivation of citizenship through unmarried U.S. citizen father) [see section], the DOS requires that the biological or blood relationship between the transmitting parent(s) and the child must be established by a preponderance of the evidence — that is, the evidence must show that the attested relationship more likely than not exists. Id. INA 309(a) cases carry a higher “clear and convincing” evidence standard [see section].

A man is considered to have a biological relationship with the child when he has a genetic parental relationship with the child. 8 FAM 301.4-1(D)(1)(c). A mother may either have a genetic parental relationship with the child or a gestational relationship to the child. We discuss scenarios involving gestational mothers in a later section [see section].

The DOS states that children born to married parents are generally presumed to be the issue of that marriage. 8 FAM 301.4-1(D)(1)(d). This presumption is not, however, determinative in derivation of citizenship cases. Id. The DOS may investigate if it has reason to doubt that the U.S. citizen parent is biologically related to the child. Id. The DOS provides a non-exhaustive list of examples of situations that may trigger scrutiny:

1. Child was conceived or born when either of the alleged biological parents were married to another person during the relevant time period;

2. Birth certificate lists a person other than the alleged biological parents;

3. Evidence or indications exist that child was conceived at a time when the alleged father had no physical access to the mother;

4. The child was conceived when the mother was married to someone other than the man claiming paternity and evidence indicates that the child may be the issue of the prior marriage; and

5. The child was born through surrogacy or other forms of assisted reproductive technology [we discuss here].

The DOS only requests DNA testing when the other evidence in the record is insufficient to establish the alleged biological relationship(s). 8 FAM 304.2.

Key Concept: Residence Requirement When Both Parents of Child Born Abroad are U.S. Citizens

The concept of “residence” only arises in the derivation of citizenship context in cases where the parents are both U.S. citizens [see section]. That either parent can satisfy the residence requirement to transmit citizenship makes this requirement relatively lenient compared to the provisions which require specific periods of physical presence. Still, in the rare case where the prospective parents of the child are uncertain about the requirement, they should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for guidance.

INA 101(a)(33) defines “residence” as the “place of general abode [meaning] his principal actual dwelling place in fact, without regard to intent.” The concept of “residence” is distinct from the concept of “physical presence.” The USCIS explains that “residence is defined in the INA as the person’s principal actual dwelling place in fact, without regard to intent.” 12 USCIS-PM 2.H(F). The DOS states that the concept of “residence involves the connection to a specific physical place.” 8 FAM 301.7-4(B). The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) has held that continuous stay as a college student for a period of three years constituted residence in the United States. Matter of M-, 4 I&N Dec. 418 (BIA 1951).

“Residence is more than a temporary presence or a visit to the United States.” 12 USCIS-PM 2.H(F)(2). Thus, temporary visits to the United States do not establish residence. Id. Working in the United States while residing in Canada or Mexico would not establish residence without an actual U.S. residence — a workplace alone does not qualify. Id.; 8 FAM 301.7-4(B). Vacations or brief stays do not constitute residence. 12 USCIS-PM 2.H(F)(2. The DOS suggests that spending a year on a cross country tour of the United States while staying in different hotels for every week would not constitute residence. 8 FAM 301.7-4(B)(j). However, as the BIA has held, attending school in the United States for an extended period may constitute residence. The DOS states that a stay of six months or more is more likely than a shorter stay to be considered “residence,” although additional evidence may be required depending on the facts of the case. 8 FAM 301.7-4(B)(h).

The USCIS makes clear that owning or renting property is not a prerequisite to establishing residence. 12 USCIS-PM 2.H(F)(2). Furthermore, owning or renting property outside the United States does not preclude a finding that the individual actually resides or resided in the United States while owning or renting property outside the United States. Id. Owning or renting property in the United States may support a claim of residence, but owning or renting property without actually living in it does not constitute residence. Id. DOS provides nearly identical analysis. 8 FAM 307.4(B)(f).

The USCIS states that, in general, an individual born in the United States can establish residence provided that he or she shows that his or her mother was not merely transiting through or visiting the United States at the time of the birth. 12 USCIS-PM 2.H(F)(3). For this reason, a long-form birth certificate showing the mother’s U.S. address will generally be sufficient to establish residence. Id. The DOS concurs that birth in the United States usually establishes residence for purpose of INA 301(c). 8 FAM 307.4(B)(g). If the individual has a foreign birth certificate or if the long-form birth certificate indicates that the mother’s address is abroad, the individual will have to prove U.S. residence through other evidence. Id. The USCIS provides a non-exhaustive list of evidence that can satisfy the residence requirement:

U.S. marriage certificate indicating the address of the bride and groom;

Property rental leases, property tax records, and payment receipts;

Deeds;

Utility bills;

Automobile registrations;

Professional licenses;

Employment records or information;

Income tax records and income records, including W-2 salary forms;

School transcripts;

Military records; and

Vaccination and medical records.

Id.; similar at 8 FAM 307.4(b)(k).

The DOS notes that residence in the Philippines from April 11, 1899, to July 4, 1946, constitutes residence in the United States. 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(b). This may still be relevant in limited derivation of citizenship cases.

The vast majority of U.S. citizens either reside in the United States or have resided in the United States in the past. However, the United States’ concept of providing citizenship to nearly all persons born in the United States means that it is somewhat easier to be a U.S. citizen without ever having resided in the United States than it is in many countries with less generous citizenship rules. Some individuals who derived citizenship themselves from one or both parents may have never resided in the United States.

Key Concept: Physical Presence Requirement for Certain U.S. Citizen Parents of Child Born Abroad

The USCIS explains that “physical presence … refers to the actual time a person is in the United States, regardless of whether he or she has a residence in the United States.” 12 USCIS-PM H.2(F). The DOS states that “[a]ny time spent in the United States or its outlying possessions … may be counted toward the required physical presence.” 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(a). With the exception of cases when the child’s U.S. citizen parents are married, the nearly all of the derivation of citizenship provisions require a period of physical presence rather than residence. Although physical presence is a broader concept than residence, it can be more evidence-intensive to establish in borderline cases.

With one exception for certain forms of employment for the U.S. government abroad, physical presence only encompasses “time actually spent in the United States [or] in its outlying possessions…” 8 FAM 301.7-3(C). The requisite periods of physical presence are discussed below in sections on specific scenarios relating to the parentage of children born outside the United States. Naturalized citizens may count time they spent in the United States prior to naturalization toward the physical presence requirement — regardless of whether they were in lawful status. 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(a).

The DOS explains that it is “usually … not necessary to compute U.S. physical presence down to the minute.” 8 FAM 301.7-3(C). But in cases where it is unclear whether the parent meets the applicable physical presence requirements, “it is important to obtain the exact dates of the parent’s entries and departures.” Id. The DOS provides that expired passports showing the parent’s entries and departures from the United States and other countries could be helpful. Id. It notes that in the case of an individual who commutes to work in the United States from Canada or Mexico, the hours spent in the United States, rather than the number of days worked, would be decisive to the physical presence question. Id. Absences from the United States, no matter how brief, do not constitute physical presence. Id.

The DOS notes that “[i]t is possible to come to several equally valid conclusions about the amount of time between two dates” for calculating physical presence. Id. The DOS generally considers a calendar year whether it has 365 or 366 days and a calendar month whether it has 28, 29, 30, or 31 days, when calculating the amount of physical presence accrued between two dates. Id.

Physical presence in any U.S. territories listed in INA 101(a)(38) after December 24, 1952, constitutes physical presence in the United States (the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, Virgin Islands of the United States, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands). However, the provision including the Northern Mariana Islands became effective on November 3, 1986. Physical presence in other U.S. possessions before December 24, 1952, also counts toward the requirement, with the exception of the Panama Canal Zone. Time spent in the Philippines from April 11, 1899, to July 4, 1946, constitutes physical presence in the United States (but time spent in the Philippines after July 4, 1946, does not). See 8 FAM 301.7(B)(b)(1)-(4).

The DOS provides that time spent on ships within U.S. territorial waters may constitute physical presence in the United States. 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(b). However, time spent on U.S. registered ships outside of U.S. territorial waters does not. Id. The DOS states that time spent on voyages that are defined as “coastal” — “those [voyages] between ports in the same State or adjacent States” — “is open to legal interpretation.” Id.

Cases Where Physical Presence Can Be Established Through Time Spent Abroad

Section 301(g) provides for two limited cases where time spent by a U.S. citizen outside the United States actually constitutes physical presence.

1. Any period of honorable service in the Armed Forces of the United States or time spent as the dependent unmarried son or daughter and a member of the household of such a person; or

2. Any period of employment with the United States Government or with an international organization as that term is defined in section 288 of title 22 by such citizen parent or time spent as the dependent unmarried son or daughter and a member of the household of such a person.

The DOS explains that “[r]esidence abroad in any capacity mentioned in [INA 301(g)] can count toward and even satisfy the required period of physical presence in the United States.” 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(c). In theory, 301(g) makes it possible for a U.S. citizen who never actually stepped foot in the United States to satisfy the eligibility requirements for transmitting citizenship in several cases, although this scenario would be very unusual. Id.

Before we continue, please note that these exceptions do not apply to INA 309(c) cases involving children born before June 12, 2017. INA 309(c) refers to the 1 year continuous physical presence requirement for an unmarried U.S. citizen mother to transmit citizenship to her child born abroad. The trade-off, however, was that the physical presence requirement for unmarried U.S. citizen mothers was shorter (albeit, it had to be continuous) than other physical presence requirements in INA 301 and 309. For cases involving children born on or after June 12, 2017, INA 301(g) applies to unmarried mothers under INA 309(c) in full, in accordance with the Supreme Court decision in Morales-Santana. This presumably includes the exceptions discussed below. We examine this issue in more detail later in the article [see section].

Qualifying Sons and Daughters

Before discuss when service with the U.S. Armed Forces, employment abroad with the U.S. Government, and employment abroad with an international organization constitute physical presence under INA 301(g), we should first understand what constitutes a “dependent unmarried son or daughter and a member of the household” in this context — since being the dependent unmarried son or daughter and member of the household of a person serving in one of the three above capacities counts as physical presence. This is significant in part because children of service members overseas may be some of the more likely beneficiaries of the INA 301(g) exception.

The DOS explains that whether the parent of the dependent child was a U.S. citizen, noncitizen U.S. national, or foreign national is irrelevant — the only question is whether the parent was working in a qualifying capacity abroad. 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(g).

The phrase “dependent” in this context “means relying on one’s parents for more than half of one’s support.” Id. If the parent dies during the foreign assignment, the child cannot count time abroad after the death toward the physical presence requirement. Id.

The term “unmarried” encompasses the statuses of “single,” “divorced,” or “widowed” — thus, any status other than being married. Id.

The DOS makes clear that there is no age limit on the term “son” or “daughter” for purpose of INA 301(g) — a significant difference from many other areas of the INA. Id. The term “son or daughter” encompasses legitimate children, legitimated children, adopted children, stepchildren, biological children of woman engaged in employment specified in INA 301(g), or biological children of a man who has acknowledged paternity. Id.

The DOS explains that in most cases, the term “member of the Household” refers to a son or daughter living with the parent engaged in qualifying employment abroad. Id. In limited cases, however, the DOS may recognize a son or daughter living apart from that parent as a member of the parent-s household. “These situations occur most often when the parent accepts an unaccompanied tour abroad or the child attends school in another foreign country during a parent’s tour of duty abroad and is away from home for most, if not all, of the year.” Id. If the individual’s parents maintain separate residences for convenience or necessity but were not estranged, the individual can count time spent at both parents’ residences — including the parent who was not engaged in qualifying employment — toward the physical presence requirement in INA 301(g). Id. However, if the parents were estranged or divorced, only time spent with the parent engaged in qualifying employment abroad can count toward the INA 301(g) requirement. Id.

Periods of Honorable Service in the U.S. Armed Forces

The DOS explains what constitutes “periods of honorable service in the Armed Forces of the United States.” 8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(d). Periods of honorable service in the U.S. Armed Forces constitute physical presence whether they occurred in the United States or overseas. For a naturalized citizen, periods abroad in honorable service in the U.S. Armed Forces count as physical presence whether they occurred prior or subsequently to naturalization. Id. The DOS notes that the USCIS has concluded that members of the Reserve components of the U.S. Armed Forces may count any time spent in active duty — except for training — toward the physical presence requirement, but not time spent in other capacities. Id. Non-duty travel for reservists do not count as physical presence. Id. Although only periods of honorable service count as physical presence, “some persons who have received other than honorable discharges may have some periods of honorable service that can be confirmed by the military authorities…” Id. Periods of alternate service performed by conscientious objectors does not count as physical presence. Id.

Employment With the U.S. Government

The DOS interprets the phrase “employment with the United States Government” in accordance with 5 USC 2105 — taking into account whether:

a. The person occupies an allocated position;

b. The person’s name appears on the payroll of a Department or agency;

c. The person has a security clearance or took an oath of office; and

d. The U.S. government has the right to hire and fire the person and to control the input and end result of the employee’s work.

8 FAM 301.7-3(B)(e).

The DOS states that whether the concept of qualifying U.S. government employment abroad is not determined by the type of passport the individual has or had. Id. The DOS states that employment abroad for non-appropriated fund instrumentalities — such as post exchanges, Stars and Stripes, and the Armed Forces Radio and Television network — may count their employment abroad for physical presence purposes under 301(g). There is no requirement that the individual must have been sent abroad by the U.S. Government — “[p]ersons employed abroad under local hire by the U.S. government can count such periods of employment toward the physical presence required by INA 301(g)…” Time spent abroad as a Peace Corps volunteer does not qualify, but time spent abroad as non-volunteer Peace Corps personnel while being a member of the Civil Service or Foreign Service does qualify. Id. Employment for a company that accepted a contract from the U.S. government to undertake a project abroad does not qualify. Id. Working for a foreign university on a grant administered by DOS does not qualify for INA 301(g) purposes. Id.

Employment With a Qualifying International Organization

The list of qualifying international organizations for which an individual can work for abroad and have that time counted as physical presence is found at 8 FAM 102.5 — which we discuss in a separate article [see article]. Beyond the chart — the DOS makes clear that missionary groups and commercial ventures do not qualify as international organizations and time spent abroad working for them cannot satisfy INA 201(g).

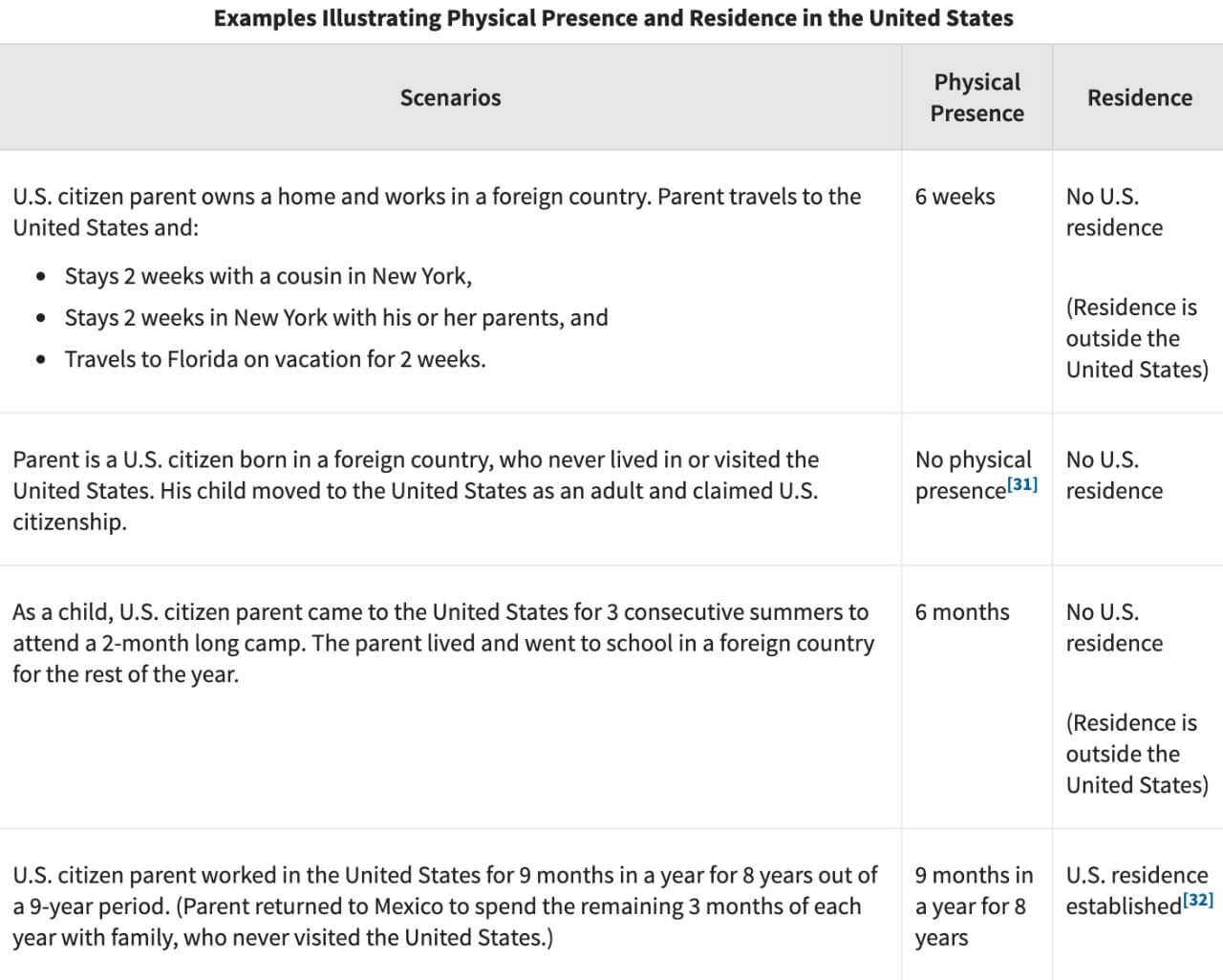

Key Concept: Illustrating the Difference Between Residence and Physical Presence

The USCIS provides a useful chart for illustrating the differences between the concepts of “residence” and “physical presence” at 12 USCIS-PM H.2(F):

Key Concept: Former Retention Requirements

The derivation of citizenship laws have changed substantially over the years. As you will see in some of our charts, certain derivation of citizenship provisions included citizenship retention requirements. Subject individuals who derived citizenship at birth abroad had to fulfill the applicable retention requirements in order to keep their citizenship. Certain retention provisions provided ways for individuals who failed to retain citizenship to regain U.S. citizenship.

The USCIS explains that Congress eliminated all of the citizenship retention requirements on October 10, 1978. 12 USCIS-PM H.3(A). This elimination, however, only applied prospectively, meaning that it did not ameliorate failures to retain citizenship prior to the elimination of the retention requirements.

Thus, the retention requirements remain relevant only to the extent that there is a question as to whether an individual who derived citizenship at birth through one U.S. citizen parent retained his or her citizenship prior to October 10, 1978, and any collateral issues that may arise from the answer.

Cases where citizenship retention issues may arise necessarily involve facts from several decades ago. Individuals whose cases may be implicated in one way or another by questions stemming from the former citizenship retention provisions should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for an assessment. For purpose of this article, we will only note when the former citizenship retention provisions applied and what they were.

Child Born Abroad of Two U.S. Citizen Parents (Married)

Under current law, the child of two U.S. citizen parents acquires citizenship at birth if at least one of the parents had resided in the United States or one of its outlying possessions. INA 301(c). The parent could have resided in the United States or one of its outlying possessions at any time, and thus does not need to be a current resident of the United States. Thus, it would be a very rare case wherein a child born abroad to two U.S. citizen parents does not acquire U.S. citizenship at birth.

These rules governing acquisition of citizenship through two U.S. citizen parents have been consistent.

Child Born Abroad of One U.S. Citizen Parent and One Noncitizen National Parent (Married)

Under current law, the child of one U.S. citizen parent and one U.S. national parent derives citizenship at birth if the U.S. citizen parent was physically present in the United States or one of its outlying possessions for at least one year. INA 301(d). The period of residence of the U.S. citizen may have occurred at any time prior to the birth of the child provided that it was for a continuous period of one year.

This scenario is relatively uncommon due to the fact that there are relatively few noncitizen nationals. Under certain circumstances, noncitizen nationals may pass nationality, but not citizenship, to children born outside of American Samoa or Swains Island [see article]. However, the child cannot derive nationality without citizenship if he or she derives citizenship at birth through INA 301(d) — noncitizen nationality can only be transmitted when there is no U.S. citizen parent. 8 FAM 301.7-4(C); INA 308.

Child Born Abroad of one U.S. Citizen Parent and One Alien Parent (Married)

Current Laws

For all births occurring on or after November 14, 1986, a child born abroad to one U.S. citizen parent and one alien parent derives citizenship at birth if the U.S. citizen parent was physically present in the United States for at least five years, with at least two years coming after the U.S. parent turned 14 years of age.

The rules for derivation of citizenship at birth through a U.S. citizen parent and an alien parent are more stringent than those for two U.S. citizen parents. However, provided that the U.S. citizen parent meets the two physical presence requirements, the child will derive citizenship under statute in the same way.

Dec. 14, 1952 — Nov. 14, 1986 Laws

For all births occurring on or after December 24, 1952, but prior to November 14, 1986, the physical presence requirement for the U.S. citizen parent is 10 years, with 5 of which having occurred after the parent turned 14. Thus, the pre-November 14, 1986, rules are far more stringent than the current rules. There were no citizenship retention requirements under these laws.

Pre-INA Laws

For all births occurring on or after January 13, 1941, and prior to December 24, 1952, the U.S. citizen parent must have resided in a U.S. possession for 10 years prior to the birth of the child, with five of which occurring after the parent turned 16. For cases where one of the parents was a U.S. citizen serving in the military between December 7, 1941, and December 31, 1946, five of the years of residence could have occurred after the U.S. citizen parent turned 12 rather than 16 for other cases. There were retention requirements for these cases.

For births before January 31, 1941, the only requirement was that the U.S. citizen parent resided in the United States before the child’s birth. There were citizenship retention requirements for births between May 24, 1934, and January 31, 1941, but not for births prior to May 24, 1934.

Child Born Abroad of U.S. Citizen Mother and U.S. Citizen Father (Unmarried)

The child of an unmarried U.S. citizen father and U.S. citizen mother may derive citizenship at birth through either the U.S. citizen father or U.S. citizen mother under section 309 of the INA. The requirements are more stringent, however, than deriving citizenship through married U.S. citizen parents. The child’s U.S. citizen father must be eligible to transmit citizenship through INA 309(a) (or a former provision, depending on the time of the birth) or the child’s U.S. citizen mother must be eligible to transmit citizenship through INA 309(c). We discuss these rules in our section on unmarried U.S. citizen fathers [see section] and unmarried U.S. citizen mothers [see section].

The FAM discusses this at 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(1).

Deriving Citizenship Through U.S. Citizen Father (Unmarried)

Under current law, a child born abroad to a U.S. citizen father and alien mother where the parents are unmarried derives citizenship at birth through the U.S. citizen father only if several conditions set forth in INA 309 are satisfied:

A blood relationship between the child and the father is established by clear and convincing evidence;

The child’s father was a U.S. citizen at the time of the child’s birth;

The child’s father (unless deceased) has agreed in writing to provide financial support for the child until the child reaches 18 years of age; and

One of the following criteria is met before the child turns 18 years of age: (1) The child is legitimated under the law of his or her residence or domicile; (2) the father acknowledges in writing and under oath the paternity of the child; or (3) The paternity of the child is established by adjudication of a competent court.

Additionally, the father must satisfy the same physical residence requirements that he would have to satisfy if he was married to the child’s alien mother. Thus, for all births on or after November 14, 1986, the father must have accrued at least five years of physical presence in the United States, with two of those years coming after the age of 14. For all births occurring on or after December 24, 1952, but prior to November 14, 1986, the physical presence requirement for the U.S. citizen parent is 10 years, with 5 of which having occurred after the parent turned 14.

The child may also derive citizenship through the U.S. citizen father if his or her mother is also a U.S. citizen but not married to the father.

Whether to Apply “Old” or “New” INA 309(a)

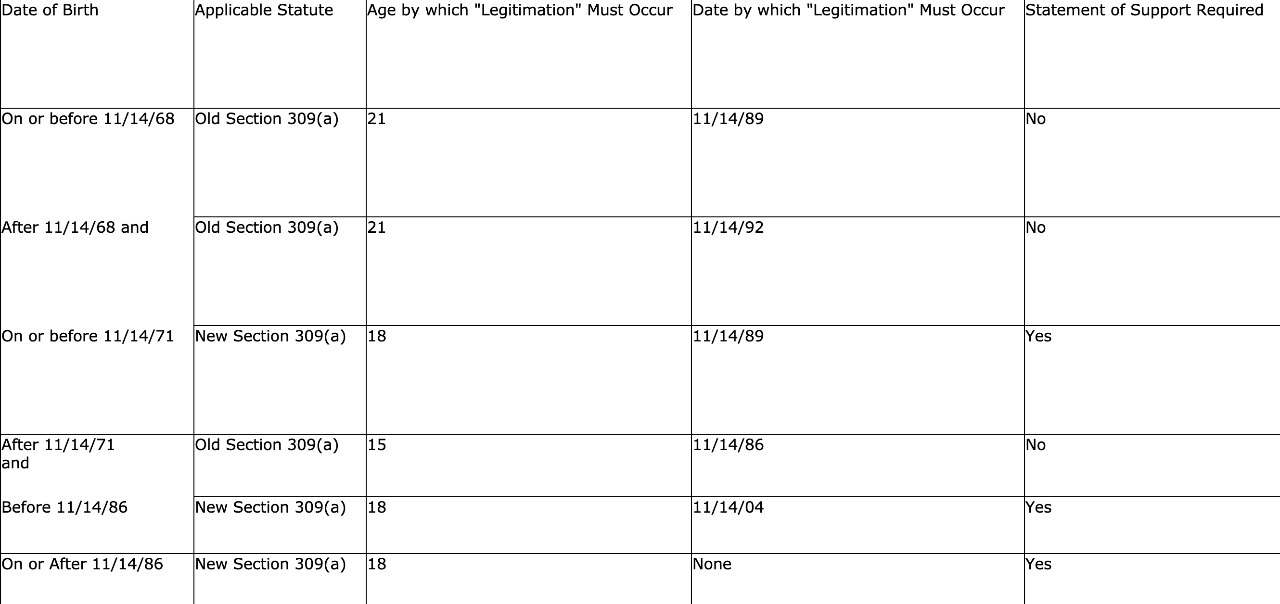

The version of INA 309(a) which applies depends on the time of the birth of the child. There are differences in the legitimization and support requirements depending on which version of the statute applies. We will discuss these in more detail in the next two subsections. The DOS provides a useful chart for determining which version of INA 309(a) applies — reproduced below from 8 FAM 301.7-7 for your convenience:

The chart demonstrates that several derivation of citizenship through an unmarried U.S. citizen father rules have evolved over the years.

First, the particulars of the legitimation requirement (see below) have changed — with the age at which legitimation must have occurred being 15, 18, or 21 depending on the time the child was born. The chart also includes the last possible date that legitimation could have occurred depending on the time at which the child was born.

Second, a statement of financial support has not always been required under the derivation of citizenship rules. The chart notes when this constituted a requirement and when it did not. We discuss the financial support requirement below.

Finally, the chart does not note the father’s physical presence requirements — but we have noted that those are identical to the physical presence requirements for transmission of U.S. citizenship by a U.S. citizen parent who is married to a non-citizen. Thus, the particular length of the father’s physical presence requirement depends on when the child was born. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3)(c)(5).

The DOS notes that the “old” version of INA 309(a) applies not only to persons who turned 18 years old as of November 14, 1986, but also “to any persons whose paternity was established by legitimation prior to that date.” 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3). The DOS notes that either the “old” or “new” INA 309(a) can apply to persons who were at least 15 years old, but under the age of 18, on November 14, 1986 (persons born after November 14, 1968, but on or before November 14, 1971). Id. The DOS stated that some of these individuals may opt for the “old” INA 309(a) rather than the current version because the law was simpler or may benefit them.

Key Concept: Establishing a Blood Relationship Under INA 309(a)

INA 309(a) requires that a blood relationship between the child and the U.S. citizen father be established through “clear and convincing evidence.” The DOS explains “that the evidence must produce a firm belief in the truth of the facts asserted that is beyond a preponderance but does not reach the certainty required for proof beyond a reasonable doubt.” 8 FAM 301.4-1(D)(1)(b). As we noted, INA 309(a) is unique in presenting a specific standard for evaluating whether there is a biological relationship between the U.S. citizen father and the child. Although DNA evidence is not required, it may help resolve cases where the other available evidence is insufficient. Id. The DOS only requests DNA evidence “when other forms of credible evidence are insufficient.” 8 FAM 304.2-1(c)-(d).

Key Concept: Legitimation

Under the current version of INA 309(a) — in effect as of November 14, 1986 — there are three ways to satisfy the legitimation requirement:

The child is legitimated under the law of the place of the child’s (not the father’s) residence or domicile;

The father acknowledges in writing and under oath the paternity of the child; or

The paternity of the child is established by adjudication of a competent court.

Provided that one of these three events occurs before the child turns 18, the legitimation requirement is satisfied. Please note that this is separate and distinct from the financial support requirement — described in the next key concept subsection.

Regarding the first method — legitimation in the place of the child’s residence or domicile — the DOS emphasizes that this refers only to the child’s place of residence or domicile, not the father’s. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3)(b)(4). The DOS states that it is best to establish eligibility for derivation of citizenship using legitimation “only in cases where the legitimating act has already taken place and evidence is readily available.” Id. How legitimation occurs varies by jurisdiction: “[l]egitimation may occur by automatic operation of law at birth, by some affirmative act of the father (for instance, marrying the mother), or by court order.” Id. For purpose of INA 309(a), the pertinent question is when the legitimating act occurred (before or after the child turned 18).

The DOS explains that the second method — acknowledgment of paternity by the father — “is the simplest means of establishing legal relationship under the ‘new INA 309(a) and should be used in most cases.” Id. “Acknowledgment may be made under oath or affirmation in any form before a consular officer or other official authorized to administer oaths.” Id. The DOS considers an acknowledgment by the father on the child’s birth certificate or otherwise under foreign procedures to suffice so long as the acknowledgment was made under oath or affirmation. Id. For children who have not been legitimated, acknowledged, or subject to court decrees of paternity, the father may execute an acknowledgment of paternity and a statement of support on the Form DS-5507 (in the DOS procedure) provided that the child is under the age of 18. Id.

The DOS explains that the third method allowed under new INA 309(a) — court adjudication of paternity — is “extremely rare.” Id. The DOS states that this method should not be used unless the father is unable or unwilling to acknowledge paternity. Id. The adjudication must have occurred before the child turned 18 — regardless of whether it occurred before or after November 14, 1986. Id. If the father has already been subjected to an adjudication of paternity — he need only submit a statement of support in order to satisfy the financial support requirement (see next section). Id. The DOS notes that because adjudications of paternity only establish a legal relationship, the applicant must still submit evidence of a blood relationship between the child and the father. Id. DOS may question the evidence of an adjudication of paternity if there is reason to believe that the court order does not establish a legal relationship between the father and child. Id.

Under the old INA 309(a) — in effect prior to November 14, 1986 — the child must have been legitimated in order to derive citizenship. However, the requirements of former INA 309(a) did not specify whether the legitimation had to occur under the laws of the United States or foreign residence or domicile of the father or the child. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3)(c). Id. However, consular officers must determine whether the legitimation occurred under the law of either the father’s or child’s residence (general abode of the person — principal, actual dwelling place in fact) or domicile (place of true, fixed, and permanent home or ties). Id. The DOS notes that in most cases, marriage between the parents prior to the child’s birth constitutes legitimation. Id. In certain cases, marriage subsequent to the child’s birth may constitute legitimation — depending on the applicable laws. Id. The marriage must have been legal under the laws of the applicable jurisdiction. Id. In cases where there was no marriage — DOS will consider whether the child was legitimated by other means under the applicable jurisdictional laws. Id. The DOS notes that these laws may vary from state to state, much less from the United States to foreign countries. Id. The DOS regards any case where the father adopted the child while the child was under the age of 21 as constituting legitimation under old INA 309(a).

Key Concept: Financial Support Requirement

INA 309(a)(3) requires that the U.S. citizen father provide a written statement of financial support for the child before the child turns 18 years old in order for the child to be deemed to have derived citizenship at birth through the father. This requirement is waived only if the father is deceased before the child turns 18. If the father declines to provide a statement of financial support before the child turns 18, the child cannot derive citizenship through the father. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3). The USCIS makes clear that it will consider whether the agreement is voluntary. 12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1).

The USCIS requires a written statement of financial support from the father that is dated before the child’s 18th birthday. 12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1). DOS provides that a local law obliging fathers to pay financial support, in the absence of a written agreement from the father, is insufficient. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3).

Provided that there is a qualifying written agreement, however, whether the father actually paid the financial support is immaterial to the child’s derivation of citizenship. Id. The DOS notes that it lacks the authority to obtain payments to enforce the agreement — and is only concerned with whether the agreement exists for derivation of citizenship purposes. Id. The USCIS also places the emphasis on whether the father accepted the legal obligation to support the child before the child turned 18, not whether the father actually followed through. 12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1). The USCIS adds that there is no provision for loss of citizenship based on the father’s failure to fulfill his legal obligations after agreeing to support the child. Id. at n.19.

While the death of the father waives this financial support requirement, the DOS notes that it must be proven that the father is dead. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3). The DOS notes that the individual has the burden of proving that the father is dead — the DOS states that the individual should provide a death certificate or other evidence of the father’s death. Id. The inability to locate the father does not waive the requirement. Id.

The USCIS states that if the child is applying for a Certificate of Citizenship before his or her eighteenth birthday, the father may provide a written agreement of financial support either along with the application or prior to the final adjudication of the application. 12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1). The USCIS may issue a Request for Evidence for the financial support agreement before deciding the petition or request that the applicant provide it at the time of an interview. Id.

Because the statute only requires that the father had agreed to provide financial support for the child before the child’s 18th birthday, a child who has already turned 18 may still be deemed to have derived citizenship at birth if he or she can proffer evidence that the father had agreed to provide financial support before his or her 18th birthday. Here, the rule is that the evidence must have existed and been finalized before the child turned 18, and the evidence must have met any applicable foreign law or U.S. law governing the child’s or father’s place of residence to establish acceptance of financial responsibility before the child turned 18. 12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1). The key question, thus, is not whether the father actually provided financial support, but whether the father had formally accepted responsibility within the meaning of INA 309(a)(3) before the child turned 18.

The USCIS lists the three requirements of a valid written agreement of financial support under INA 309(a)(3):

The document must be in writing and acknowledged by the father;

The document must indicate the father’s agreement to provide financial support for the child; and

The document must be dated before the child’s 18th birthday.

12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1).

The USCIS may consider an agreement signed by a judge rather than the father to satisfy the acknowledgment requirement provided that there is evidence in the record of proceedings that the father consented to the determination of paternity. Id. at n.18.

The DOS offers the Form DS-5507, Affidavit of Parentage, Physical Presence, and Support, which “contains a statement of support which satisfies the requirements of ‘new’ INA 309(a).” 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3).

The USCIS notes that a written agreement of financial support may come in different forms. It provides a non-exhaustive list of examples of documentation that may satisfy the statutory requirement:

A previously submitted Affidavit of Support (Form I-134) or Affidavit of Support Under Section 213A of the INA (Form I-864);

Military Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS) enrollment;

Written voluntary acknowledgment of a child in a jurisdiction where there is a legal requirement that the father provide financial support;

Documentation establishing paternity by a court or administrative agency with jurisdiction over the child’s personal status, if accompanied by evidence from the record of proceeding establishing the father initiated the paternity proceeding and the jurisdiction requires the father to provide financial support; or

A petition by the father seeking child custody or visitation with the court of jurisdiction with an agreement to provide financial support and the jurisdiction legally requires the father to provide financial support.

12 USCIS-PM 3.H(C)(1).

Taken together, both the USCIS and DOS provide detailed guidance on what constitutes a valid financial support agreement under the INA. Despite some differences in emphasis, the guidance is mostly consistent for seeking proof of citizenship from USCIS or DOS.

Older Rules

For children born on or after January 13, 1941, and December 24, 1952, the father must have been physically present in the United States for 10 years prior to the birth of the child, with at least 5 years coming after the age of 14 (or in certain cases, the requirement was 10 years with 5 coming after the father turned 16). Employment abroad with the U.S. military, Government, or qualifying international organization could be included. The paternity of the child must have been established before the child turned 21 under the legitimation law of the father’s or child’s residence or domicile before December 24, 1952. For births prior to January 13, 1941, the only requirements were that the father resided in the United States before the child’s birth and that the child was legitimated under the law of the father’s U.S. or foreign domicile.

All cases discussed in this section for children born after noon (EST) on May 24, 1934, had citizenship retention requirements. There were no retention requirements for births before noon (EST) on May 24, 1934.

Deriving Citizenship Through U.S. Citizen Mother (Unmarried)

Deriving citizenship through an unwed U.S. citizen mother is less complicated than doing so through an unwed U.S. citizen father. However, a June 12, 2017 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States increased the physical presence for U.S. citizen mothers prospectively — in a change we will examine in this section.

Children Born On or After December 23, 1952 and Before June 12, 2017

Under INA 309(c), U.S. citizen mothers only had to satisfy two requirements to transmit citizenship to children born on or after December 23, 1952, and before June 12, 2017:

Have been a U.S. citizen at the time of the child’s birth; and

Have been physically present in the United States or one of its outlying possessions for 1 continuous year prior to the child’s birth.

INA 309(c) is substantially more generous than the provision for transmittal of U.S. citizenship through unmarried U.S. citizen fathers. First, INA 309(c) contains to equivalent to the financial support and legitimation requirements of INA 309(a). Second, INA 309(c) requires only that the mother accrue 1 year of continuous physical presence in the United States, whereas INA 309(a) requires fathers to accrue either 5 or 10 years of physical presence with certain amounts of physical presence after a certain age. (applicable requirement depends on when the child was born).

The DOS notes that the continuous physical presence requirement for these cases must be satisfied by physical presence in the United States: “The 1966 amendment to INA 301 allowing members of the U.S. armed forces, employees of the U.S. government and certain international organizations, and their dependents to count periods outside the United States as U.S. physical presence does not apply to INA 309(c).” (Emphasis added.) 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3). However, it bears mentioning that the physical presence requirements under INA 309(c) are far more lenient than those under INA 301.

Children Born On or After June 12, 2017

On June 12, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States invalidated the portion of 309(c) requiring the U.S. citizen mother to have only accrued one year of continuous physical presence in order to transmit citizenship. Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 137 S.Ct. 1678 (2017) [PDF version] [see article]. The Supreme Court remedied the defect it found in INA 309(c) by requiring unwed U.S. citizen mothers to prospectively meet the same physical presence requirements as unwed U.S. citizen fathers under INA 309(a) in order to transmit citizenship.

Thus, the USCIS explains that “[t]he U.S. Supreme Court indicated that the 5 years of physical presence (at least 2 years of which were after age 14) requirement should apply prospectively to all cases involving a child born out of wedlock outside the United States to one U.S. citizen parent and one alien parent, regardless of the gender of the parent.” 12 USCIS-PM H.2(C)(2); see also 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(3) [same from DOS]. The FAM specifies that INA 301(g) applies to post-Morales-Santana cases. Although the FAM does not say so expressly, this suggests that the limited exceptions for when time spent abroad can constitute physical presence in the United States (i.e., honorable U.S. military service, government employment, qualifying international organization employment) should apply in cases involving children born on or after June 12, 2017 [see section].

Thus, in order to transmit U.S. citizenship to a child born on or after June 12, 2017, the unmarried U.S. citizen mother must have been a citizen at the time of the child’s birth and must have accrued at least 5 years of physical presence in the United States, with at least 2 years of physical presence after she turned 18 years old. However, other requirements for U.S. citizen fathers under INA 309(a) — such as legitimation or support agreements — still do not apply to INA 309(c) cases.

Old INA 309(a) Applicable to Certain Unmarried Mothers

The DOS explains that the old version of INA 309(a) — in effect until November 14, 1986, did not apply exclusively to unmarried U.S. citizen fathers. This allowed U.S. citizen mothers who could not meet the continuous physical presence requirement of INA 309(c) to instead transmit citizenship through old INA 309(a). 8 FAM 301.7-4(e). However, in order for a mother to transmit under old INA 309(a), the child’s paternity must have been established by legitimation prior to the child’s turning 21. Id. Furthermore, the mother would have to have satisfied the physical presence requirement applicable to fathers under old INA 309(a). Id. This scenario is only possible in cases governed by old INA 309(a), as the current INA 309(a) applies only to fathers [see section for chart on which version of INA 309(a) applies]. This scenario was likely uncommon even at the time since a situation where a mother would have been eligible to transmit citizenship through old 309(a) but not 309(c) would have required a very particular set of facts.

Older Rules

For children born on or after May 24, 1934 (noon EST), but prior to December 24, 1952, the mother need only have resided in the United States or a U.S. possession prior to the child’s birth in order to transmit citizenship (this period was covered by two different statutes but the requirements remained the same). Unmarried U.S. citizen mothers transmitted citizenship to their children born before May 24, 1934 (noon EST), if they resided in the United States or a U.S. possession before the child’s birth and if the child was not legitimated by an alien father before January 13, 1941.

Child Born Abroad of U.S. Citizen Parent and Noncitizen National Parent (Unmarried)

The rules for derivation of citizenship for the child born abroad of a U.S. citizen parent and noncitizen parent are identical regardless of whether the parents are married. 8 FAM 301.7-4(E)(2). Thus, please refer to our section on cases where the parents are married for a discussion of the rule [see section].

Special Case: Child Born Abroad Through Assisted Reproductive Technology

The USCIS explains that children born abroad through assisted reproductive technology to a U.S. citizen gestational mother who is not also the genetic mother of the child can derive citizenship under INA 301 or INA 309 if the following requirements are met:

The person’s gestational mother is recognized by the relevant jurisdiction as the child’s legal parent at the time of the person’s birth; and

The person meets all other applicable requirements under either INA 301 or INA 309.

12 USCIS-PM H.3(A).

The DOS explains that the applicable provision of INA 301 or INA 309 will depend on the relationship between the child’s legal parents. 8 FAM 304.3-1.

In cases where the U.S. citizen gestational mother is the legal parent of the child at the time of the child’s birth in the place of the child’s birth, the applicable statute depends on the marital status of the mother, not the identities of the child’s biological parents. Id. Thus, if the mother is married to a U.S. citizen, INA 301(c) would apply. Id. If the mother is married to an alien, INA 301(g) would apply. If the mother is unmarried, INA 309(c) would apply. Id.

Surrogate Cases

The rules for surrogates are more complex and often depend on the child’s biological parents.

If the biological parents of a child born abroad to a surrogate are a U.S. citizen mother and a U.S. citizen spouse, the child is considered to have been born to married U.S. citizen parents, meaning INA 301(c) applies. 8 FAM 304.3-2.

If one of the child’s biological parents is a U.S. citizen and the other is the U.S. citizen’s alien spouse, INA 301(g) applies since the child is considered that of married U.S. citizen and alien parents. Id.

If only one of the child’s biological parents is a U.S. citizen, then the child will be treated as the child of an unmarried U.S. citizen mother or U.S. citizen father — whichever is applicable — regardless of the marital status of the child’s legal parents. Id.

If the child’s biological parents are anonymous sperm and egg donors, citizenship cannot be transmitted to the child at birth when the gestational mother is a surrogate even if she is a U.S. citizen. Id.

A U.S. citizen parent or U.S. citizen parents hoping to transmit citizenship to a child born abroad to a surrogate mother should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance.

Special Case: Posthumous Children Born Abroad

As we noted in previous sections, a child can acquire citizenship through a U.S. citizen parent, or U.S. citizen parents, who died prior to the child’s birth. 8 FAM 304.4.

Obtaining a Certificate of Citizenship

A person who obtains citizenship at birth through INA 301 or INA 309 is not required to obtain a Form N-600, Certificate of Citizenship. However, the USCIS handles applications for Certificates of Citizenship from those who wish to have such documentation. 12 USCIS-PM H.3(D). An individual may also seek a passport from DOS, which also serves as proof of citizenship. Id.

Persons who are at least 18 years old may file for a Form N-600 on their own behalf. For those under the age of 18, a parent or legal guardian must apply. Id.

Form N-600 applicants must appear in person for an interview with USCIS. 12 USCIS-PM H.3(E). The parent or legal guardian of an applicant under the age of 18 must also appear. Id. However, the USCIS has discretion to waive the interview requirement if it has sufficient documentation in its records to establish the citizenship of the Form N-600 applicant. This may occur in cases where the application is accompanied by one of the following documents:

Consular Report of Birth Abroad (FS-240);

Applicant’s unexpired U.S. passport issued initially for a full 5 or 10-year period; or

Certificate of Naturalization of the applicant’s parent or parents.

If approved, the USCIS will issue the oath of allegiance. Id. The USCIS will not issue the oath, however, if it determines that the person is unable to understand its meaning or, in most cases, if the person is under the age of 14. Id.

If the application for a Form N-600 is denied, the applicant may appeal within 30 days of service of the decision (or 33 days if the decision was mailed). Id.

Applicants may apply for the Certificate of Citizenship online [see article]. The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) has explained that the Form N-600 is merely evidence of citizenship, and is not in and of itself dispositive to the question of whether one is a citizen [see article].

Conclusion

The applicable derivation of citizenship rules for children born abroad depend on when the child was born and the marital situation of the U.S. citizen parent(s). In general, concerned prospective parents who may have a child abroad should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for guidance on whether their child would derive citizenship at birth abroad. Those seeking proof or recognition of citizenship for themselves or on behalf of a child born abroad should consult with an experienced immigration attorney — this may be especially important in cases where one is trying to establish derivation of citizenship under older versions of the immigration laws.

You can learn more about citizenship and naturalization generally by seeing our growing selection of articles on the subject [see category].

Resources and Materials:

Kurzban, Ira J. Kurzban’s Immigration Law Sourcebook: A Comprehensive Outline and Reference Tool. 14th ed. Washington D.C.: ALIA Publications, 2014. 1788-89, Print. Treatises & Primers. (Cited for pre-1986 derivation of citizenship provisions)