- Introduction: Matter of Velasquez-Rios, 27 I&N Dec. 470 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 470-71

- Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 471

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Velasquez-Rios, 27 I&N Dec. 470 (BIA 2018)

On October 4, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) published an immigration precedent decision in Matter of Velasquez-Rios, 27 I&N Dec. 470 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. In the decision, the Board held that the retroactive amendment of a criminal statute reducing the maximum sentence that could be imposed from 365 days (i.e., one year) to 364 days does not affect the determination that the an alien’s past conviction, prior to the amendment, was for a crime involving moral turpitude for which a sentence of one year or more could be imposed (covered by section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)).

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of Matter of Velasquez-Rios, the Board’s analysis and conclusions, and what the decision means going forward.

Please see our relevant sections on site to learn more about criminal aliens [see category] and removal and deportation defense [see category]. To read about other BIA precedent decisions, please see our growing collection of articles [see category].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 470-71

The respondent, a native and citizen of Mexico, entered the United States without inspection at an unknown time and place.

On July 22, 2003, the respondent was convicted of possession of a forged instrument in violation of section 475(a) of the California Penal Code. The respondent was sentenced to 12 days’ incarceration.

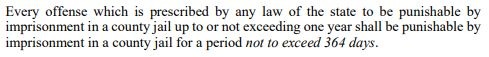

At the time of the respondent’s conviction and the Immigration Judge’s decision, the maximum sentence that could be imposed for a conviction in violation of section 475(a) of the California Penal Code was 365 days of (i.e., one year) imprisonment. You may read the text of the first version of the amendment below:

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent based on his being inadmissible under section 212(a)(6)(A)(i) of the INA for being present in the United States without having been admitted or paroled. The respondent conceded removability, but he sought cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1) of the INA. Section 240(b)(1)(C) provides that no alien who has been convicted of an offense under section 237(a)(2) of the INA [see article] is eligible for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1). Although the respondent had only been sentenced to 12 days in prison upon his conviction for possession of a forged instrument in violation of section 475(a) of the California Penal Code, the immigration judge determined that the respondent’s conviction was a crime involving moral turpitude for which a sentence of one year or more in prison could be imposed, as described in section 237(a)(2)(A)(i) of the INA. Accordingly, the Immigration Judge found that the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal and ordered him removed on December 11, 2014.

Subsequent to the respondent’s appealing the Immigration Judge’s decision, California amended section 18.5 of the California Penal Code. Under the amendment, the maximum term of imprisonment under section 475(a) and other statutes became 364 days instead of 365. This amendment took effect on January 1, 2015. This amendment was potentially significant with respect to the respondent’s conviction because section 237(a)(2)(A)(i) of the INA only addresses crimes involving moral turpitude for which a sentence of one year or more can be imposed.

Notwithstanding the enactment of section 18.5 of the California Penal Code, the Board initially dismissed the respondent’s appeal in an unpublished decision. The Board noted that, at the time of the respondent’s conviction, the maximum sentence that could be imposed was one year. The section 18.5 amendment did not take effect until well after the respondent’s conviction. Furthermore, the Board observed that nothing in the language of section 18.5 suggested that it had retroactive effect.

The respondent filed a petition for review of the BIA’s decision with the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. While the petition was pending before the Ninth Circuit, California amended section 18.5 to “apply retroactively” to all convictions, including those that occurred before January 1, 2015. This amendment took effect on January 1, 2017. The Government filed a motion before the Ninth Circuit asking for the case to be remanded to the BIA in order to allow the Board to address the new amendment. The Ninth Circuit granted the motion, returning the case to the Board.

Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 471

As we discussed, section 240(b)(1)(C) renders ineligible for cancellation of removal an applicant who was convicted of an offense under section 237(a)(2) of the INA. In order for a crime involving moral turpitude to render an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(I), the conviction must be in violation of a statute for which a sentence of one year or longer could be imposed, regardless of the actual length of the sentence imposed. The Board agreed with the immigration judge that the respondent’s forgery offense was clearly a crime involving moral turpitude within the meaning of section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(I), although it noted in a footnote that the offense qualified for the “petty offense exception,” under section 212(a)(2)(A)(ii)(II), from the inadmissibility provision for crimes involving moral turpitude at .

For the following reasons, the Board concluded that, notwithstanding the most recent version of section 18.5 of the California Penal Code, the respondent’s conviction was for a crime involving moral turpitude under section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(I) of the INA.

The Board recognized that section 18.5 retroactively modified the maximum possible sentence for the respondent’s conviction under California law. However, the Board held that “it does not affect the immigration consequences of his conviction under section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the [INA], a Federal law.”

The Board explained that section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(II), “[b]y its plain terms … is concerned with whether an alien has been convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude for which a sentence of 1 year or longer ‘may be imposed.’” The Board explained that this statutory language “calls for a backward-looking inquiry into the maximum possible sentence the alien could have received for his offense at the time of his conviction.” The Board concluded that the amendment to section 18.5 of the California Penal Code did not change the fact that the respondent could have been sentenced to 365 days of imprisonment at the time of his conviction, and thus it did not alter the applicability of section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the INA to that conviction. The Board noted that its conclusion was consistent with its “long-standing practice of examining the statute of conviction and applicable penalty that existed under the law in effect at the time the conviction was entered,” citing to Matter of Esfandiary, 16 I&N Dec. 659, 660 (BIA 1979) [PDF version]; and Matter of A-, 4 I&N Dec. 378, 381 (C.O. 1951).

The Board found support for its conclusion in the decision of the Ninth Circuit in United States v. Diaz, 838 F.3d 968 (9th Cir. 2016) [PDF version], cert. denied sub non. Vasquez v. United States, 137 S.Ct. 840 (2017). Diaz concerned the applicability of 21 U.S.C. 841(b)(1)(A) (2006), a Federal sentence enhancement statute which applies to defendants convicted of a Federal offense following the commission of multiple State drug felonies. In this case, California had retroactively reclassified certain State drug felonies as misdemeanors. On this basis, the petitioner argued that he had not been convicted of two or more State drug felonies and that, without these predicate offenses, 21 U.S.C. 841(b)(1)(A) did not apply. However, the Ninth Circuit rejected this logic, holding that “federal law, not California law,” was the pertinent consideration for determining whether the Federal sentence enhancement provision applied. Id. at 972.

The Ninth Circuit explained that the only consideration when weighing the applicability of 21 U.S.C. 841(b)(1)(A) was whether the defendant had been convicted of two or more State felony drug offenses prior to his Federal offense. The Ninth Circuit concluded that the California amendment left unchanged “the historical fact that, for purposes of [section] 841, the defendant had been convicted of a felony in the past.” Id. at 973. It added that California’s decision to retroactively reclassify certain drug offenses as misdemeanors had “no bearing on whether [section] 841’s requirements [were] satisfied.” Id. at 972. While it noted that California’s decision to give its amendment retroactive effect was relevant in the context of California State law, it held that it did not render the petitioner’s felony convictions misdemeanors for the purpose of Federal law.

In Diaz, the Ninth Circuit relied heavily upon the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in McNeill v. United States, 563 U.S. 816 (2011) [PDF version]. McNeill concerned 18 U.S.C. 924(e)(2)(A)(ii) (2006), another Federal sentence enhancement statute which covered State serious drug offense crimes for which a maximum sentence of ten years or more is prescribed by law. At the time of the petitioner’s conviction, the maximum term of imprisonment for his conviction was at least ten years. However, subsequent to his conviction, North Carolina reduced the maximum sentence to less than 10 years. Based on this reduction, the petitioner argued that his conviction no longer qualified as a serious drug offense for purposes of 18 U.S.C. 924(e)(2)(A)(ii). However, a unanimous Supreme Court rejected the petitioner’s argument, finding that “the maximum sentence applicable to a defendant’s previous drug offense at the time of his conviction for that offense…” controlled. Id. at 820. The Court added that consulting current State law rather than the State law in effect at the time of the conviction would lead to “absurd results…” Id. at 822.

The Board concluded that the logic of the decisions in McNeill and Diaz “applies with equal force to this case.” It explained that it “must use Federal law, rather than State law, to determine the immigration consequences of the respondent’s California conviction.” For this reason, it held that “[s]ection 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) … requires a backward-looking inquiry into the maximum possible sentence the respondent could have received for his forgery offense at the time of his conviction.”

At the time of the respondent’s conviction in 2003, “the maximum possible sentence for the crime was 365 days.” Because the Board held that it must look at the maximum possible sentence at the time of the conviction, it concluded that the subsequent enactment of section 18.5 had no effect on the applicability of section 237(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) to the respondent’s 2003 forgery offense. For this reason, the Board held that the respondent’s forgery conviction remained a crime involving moral turpitude for which a sentence of one year or more could be imposed, and that he was, as a consequence, ineligible for cancellation of removal. Thus, the Board dismissed the respondent’s appeal.

Conclusion

The Board’s conclusion in Matter of Velasquez-Rios is significant in light of many states changing their criminal laws to minimize the potentially adverse immigration consequences of convictions. In the decision, the Board made clear that the relevant concern when assessing whether a State offense falls under an INA provision is the language of the State statute at the time of conviction. Thus, in the instant case, the pertinent maximum sentence was that which was in effect at the time the sentence was imposed. While California’s provision limiting the maximum sentence imposed applies retroactively in the State context, it does not change the immigration consequences of prior convictions.

An alien facing removal proceedings should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately. An experienced attorney will be able to assess the facts of the alien’s specific case and the most current laws and precedents and assist the alien throughout proceedings.