- Introduction: Matter of Mohamed, 27 I&N Dec. 92 (BIA 2017)

- Respondent’s Criminal History: 27 I&N Dec. at 92-93

- Relevant Statute

- Respondent’s Proceedings in Immigration Court: 27 I&N Dec. at 93-95

- Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 95-99

- Distinguishing from Case Involving New York Law: 27 I&N Dec. 97 & n.6

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Mohamed, 27 I&N Dec. 92 (BIA 2017)

On September 5, 2017, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published for-precedent decision in the Matter of Mohamed, 27 I&N Dec. 92 (BIA 2017) [PDF version]. The decision concerned the meaning of “conviction” for immigration purposes under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). In Matter of Mohamed, the Board held that entry into a pretrial intervention agreement under Texas law qualifies as a “conviction” under section 101(a)(48)(A) because it met the following two conditions. First, the respondent must have admitted to sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt at the time of his or her entry into the pretrial intervention agreement. Second, the judge must have authorized an agreement under which the respondent is ordered to participate in a pretrial intervention program that requires the respondent to complete community supervision and community service, pay fines and restitution, and comply with a no-contact order.

In this article, we will examine the facts and procedural history of Matter of Mohamed, the Board’s reasoning and conclusion, and what the decision will mean as precedent law going forward.

Respondent’s Criminal History: 27 I&N Dec. at 92-93

The respondent, a native and citizen of Somalia, was admitted to the United States as a lawful permanent resident on December 1, 2004.

On October 31, 2012, the respondent was indicted for possession of a controlled substance with intent to deliver in violation of section 481.113(c) of the Texas Health and Safety Code.

On February 19, 2016, the respondent entered into a pretrial intervention agreement. The pretrial intervention agreement included the following terms as related by the Board:

1. 24 months of community supervision;

2. $60 per month community supervision fee;

3. 100 hours of community service;

4. Restitution in the amount of $140;

5. $500 pretrial intervention program fee; and

6. No contact with the co-defendant.

The respondent also agreed to waive his right to a speedy trial as part of the agreement. Furthermore, the respondent agreed that if he violated the terms of the pretrial intervention agreement during the 24-month period of community supervision he would be required to:

Appear in court;

Enter a plea of guilty to the charged offense;

Allow a “stipulation of evidence” of his guilt to be admitted into evidence without objection; and

Either accept the sentence offered by the prosecution or allow the judge to determine the sentence following a contested punishment hearing.

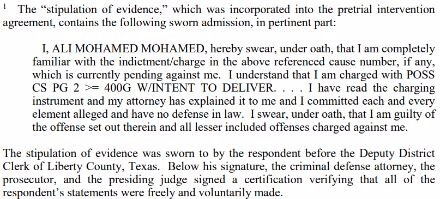

As we will examine in the Board’s analysis, the stipulation of evidence would end up being significant in its determination that the respondent had been “convicted” as defined in the immigration laws. The Board excerpted the stipulation of evidence at 27 I&N Dec. at 93 & n.1:

The prosecution agreed to dismiss the case if the respondent complied with all of the terms of the agreement and the rules of his community supervision.

During the 24-month period, the respondent was, among other things:

Required to cooperate and maintain contact with his Community Supervision Officer;

Subject to random searches of his person, home, and possessions;

Required to submit to random urine analysis; and

Required to obtain prior permission to change his address or leave the United States for an overnight stay.

The respondent’s participation in the pretrial intervention program was authorized by the presiding judge. The judge ordered the respondent to pay all fees specified in the rules of the community supervision.

The Board summarized the respondent’s criminal record as follows:

The October 31, 2012 indictment; and

The February 19, 2016 pretrial intervention agreement, detailed above.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiated removal proceedings against the respondent based on his criminal record. In proceedings, the respondent conceded alienage, but he denied that he was removable on the charge that he had been convicted of a crime. The respondent moved to terminate proceedings, arguing that his pretrial intervention agreement was distinguishable from deferred adjudication and thus was not a “conviction” as defined at section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA.

Relevant Statute

Section 101(a)(48)(A) defines the term “conviction” as follows:

[A] formal judgment of guilt of the alien entered by a court or, if adjudication of guilt has been withheld, where-

a judge or jury has found the alien guilty or the alien has entered a plea of guilty or nolo contendere or has admitted sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt, and

the judge has ordered some form of punishment, penalty, or restraint on the alien’s liberty to be imposed.

As we will examine, the central question in the case was whether the respondent’s pretrial intervention agreement constituted a “conviction” as defined in the above section of the INA.

Respondent’s Proceedings in Immigration Court: 27 I&N Dec. at 93-95

The Immigration Judge granted the respondent’s motion. The Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent’s pretrial intervention agreement was not a “conviction” under section 101(a)(48)(A), which requires that in order for a deferred adjudication to constitute a conviction under the INA the adjudication of guilt must be withheld. The Immigration Judge thus distinguished the respondent’s pretrial intervention agreement in Texas from a “deferred adjudication” under article 42.12, section 5 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure.

The Immigration Judge reasoned that a pretrial intervention agreement in Texas differed from a deferred adjudication in that under the pretrial intervention agreement, charges may be dismissed before the defendant either enters a formal plea or the judge makes a formal finding of guilt. Conversely, under the deferred adjudication provision in Texas, the defendant must first either plead guilty or nolo contendere (no contest) and the judge must make a judicial finding that the available evidence substantiates the guilt of the defendant. For this reason, the Immigration Judge determined that, because there was no adjudication of guilt entered in the record in a pretrial intervention agreement, there was no adjudication of guilt withheld for purpose of section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA. The Immigration Judge also determined that the imposition of fees and associated costs in a pretrial intervention agreement in Texas did not constitute a “form of punishment, penalty, or restraint on an alien’s liberty” that is “ordered” by a judge under section 101(a)(48)(A)(ii) of the INA.

The question of whether the respondent’s pretrial intervention agreement was distinguishable from deferred adjudication in Texas was especially significant since both the Board and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit had weighed in on the deferred adjudication statute in precedential decisions. In the Matter of Punu, 22 I&N Dec. 224 (BIA 1998) [PDF version], the Board held that “deferred adjudication” under article 42.12, section 5 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure was a “conviction” under the INA. The Fifth Circuit — under whose jurisdiction the instant case arose — held the same in Madriz-Alvarado v. Ashcroft, 383 F.3d 321 (5th Cir. 2004) [PDF version].

In addition, the Immigration Judge relied on two Texas Attorney General Opinions in reaching the conclusion that entry into the pretrial intervention agreement did not constitute a conviction. First, in a 2013 opinion, the Texas Attorney General stated that (as excerpted by the Board) “the purpose of pretrial intervention is to provide the defendant with an opportunity to have the charges dismissed prior to a finding of guilt or innocence.” Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. GA-0966, at 2 (Feb. 5, 2013). In a 2003 Attorney General Opinion, the Attorney General of Texas took the position that participants in pretrial intervention programs are not ordered to receive services by the court, but instead receive such services under an agreement with a prosecutor. Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. GA-0114, at 4 (Oct. 8, 2003). However, as the Immigration Judge recognized, section 102.012 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, amended in 2005, provided courts with jurisdiction to order the payment of fees in accord with a pretrial intervention agreement entered into by a defendant and the prosecuting agency. The provision thus allows for a court to order the payment of a “supervision fee” as a condition for entry into a pretrial intervention program for any expenses either incurred as a result of the program or necessary to the defendant’s successful completion of the program and satisfaction of the terms of the agreement. Nevertheless, in conjunction with the 2003 Attorney General Opinion, the Immigration Judge determined that the amendment was administrative because the fees that courts could order were the same as those agreed upon by the prosecutor and the defendant.

For the foregoing reasons, the Immigration Judge determined that the respondent had not been “convicted” under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA because his entry into a pretrial intervention agreement was not a “conviction” under the INA. For this reason, the Immigration Judge determined that the DHS had failed to meet its burden to establish the respondent’s removability and terminated proceedings. The DHS appealed the decision to the BIA.

Board’s Analysis and Conclusions: 27 I&N Dec. at 95-99

The question before the Board on appeal was whether the respondent’s entry into a pretrial intervention agreement under Texas law qualified as a conviction under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA. For the foregoing reasons, the Board concluded that it did, thereby reversing the decision of the Immigration Judge.

In Matter of Roldan, 22 I&N Dec. 512, 516 (BIA 1999) [PDF version], the Board stated that whether a conviction exists under the INA is a matter of Federal rather than State law. The Board, and numerous circuits, reasoned that had Congress intended for the existence of a “conviction” for immigration to depend on State law rather than Federal law it would have stated as much. Accordingly, the issue of whether the pretrial intervention agreement was a “conviction” under Texas law was not pertinent. The question before the Board was whether it was a conviction under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA.

The Board explained that, because the term “conviction” is explicitly defined for immigration purposes at section 101(a)(48)(A), the statutory definition alone governs what qualifies as a “conviction” under the immigration laws.

The Board explained that it was clear that the respondent’s pretrial intervention agreement was not a conviction deriving from “a formal judgment of guilt of the alien entered by a court.” However, it was less clear whether the respondent had been convicted as defined in section 101(a)(48)(A) because the “adjudication of guilt has been withheld.” As we noted, the Immigration Judge concluded that he had not been convicted.

The Board explained that section 101(a)(48)(A)(i) requires that to establish that an alien had been convicted by way of an adjudication of guilt that has been withheld it must be shown that:

A judge or jury has found the alien guilty; or

The alien has entered a plea of guilty or nolo contendere; or

The alien has admitted sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt.

Accordingly, the Board noted that, under the language of section 101(a)(48)(A)(i), it is not necessary that a judge or jury have found the alien guilty or that the alien have entered a plea of guilty or nolo contendere in order for a “conviction” to have occurred under the INA. This is because the section is written in the disjunctive, meaning that it sets forth three distinct ways of meeting the section 101(a)(48)(A) requirement, including that the alien has admitted sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt. The Board cited to its published decision in Matter of Richmond, 26 I&N Dec. 779, 787 (BIA 2016) [see article], wherein it discussed the attribution of different meanings to terms connected in the disjunctive in the INA.

The Board would find that the respondent’s admission of guilt in the stipulation of evidence agreement satisfied section 101(a)(48)(A)(i). However, provided that one of the three conditions in section 101(a)(48)(A)(i) is met, section 101(a)(48)(A)(ii) imposes a second requirement, namely, it must be demonstrated that “the judge has ordered some form of punishment, penalty, or restraint on the alien’s liberty to be imposed.” The Board would also find that the respondent’s entry into the pretrial intervention program satisfied the second requirement.

Regarding section 101(a)(48)(A)(i), the Board determined that the respondent’s sworn admission of guilt was sufficient for establishing that he “admitted sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt.” Under oath, the respondent admitted in the stipulation of evidence that he “committed each and every element alleged and ha[d] no defense in law.” Furthermore, he admitted that he was guilty both of the offense set out in the indictment “and all lesser included offenses charged…” He also agreed that any violation of the terms of the pretrial intervention agreement would result in a conviction based on his stipulation of guilt.

Regarding section 101(a)(48)(A)(ii), the Board determined that the obligations incurred by the respondent in the pretrial intervention program “individually and cumulatively constitute a ‘form of punishment, penalty, or restraint on the alien’s liberty…’” The Board noted that the agreement imposed costs, conditions, and restrictions to which the respondent had to agree in return for a promise from the prosecution to dismiss the charges against him. The Board cited to the Fifth Circuit decision in United States v. Hayes, 32 F.3d 171, 172 (5th Cir. 1994) [PDF version], wherein the Fifth Circuit held that “[r]estitution is a criminal penalty.” Additionally, the Board cited to its own decision in Matter of Cabrera, 24 I&N Dec. 459, 460-62 (BIA 2008) [PDF version], wherein it held that the imposition of costs and surcharges in conjunction with a deferred adjudication in Florida fell within the meaning of “penalty” or “punishment” under section 101(a)(48)(A)(ii).

The Board disagreed with the Immigration Judge’s conclusion that the program fees imposed on the respondent were merely contract terms determined by the prosecutor rather than a penalty ordered by a judge. The Board noted that, since 2005, amended article 102.012 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, under which the fees were ordered, has provided that the payment of such fees are ordered by a court. The Immigration Judge had relied on a 2003 Texas Attorney General opinion in reaching his conclusion, which of course predated the current article 102.012. However, the Board noted that even at the time the opinion was issued, “a defendant could only enter into a pretrial intervention agreement, and therefore a pretrial intervention program, with the court’s authorization.” The Board concluded that because only a judge can authorize a pretrial intervention agreement, which includes terms such as fees, community supervision, community service, restitution, and a no-contact order, the respondent’s entry into the pretrial intervention program under Texas law fell under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA.

Because the Board determined that the respondent’s entry into a pretrial intervention program fell under section 101(a)(48)(A), the Board concluded that the respondent had been “convicted” for purposes of the immigration laws. Accordingly, the Board concluded that the Immigration Judge was incorrect to terminate removal proceedings. The Board sustained the DHS’s appeal and reinstated removal proceedings against the respondent, remanding the record to the Immigration Judge for proceedings consistent with its opinion.

Distinguishing from Case Involving New York Law: 27 I&N Dec. 97 & n.6

At note 6 of its decision, the Board discussed an interesting decision of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in Iqbal v. Bryson, 604 F.Supp. 2d 822 (E.D. Va. 2009) [PDF version]. The Board explained that the district court had held that the alien’s entry into a pretrial intervention agreement under New York law was not a conviction under section 101(a)(48)(A) of the INA. The court held in Iqbal that the alien had not admitted to “sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt.” Instead, the alien had only “accept[ed] responsibility for [his] behavior.” Id. at 826. More broadly, the district court stated that “mere boilerplate language that appears to be used in all of New York’s Pretrial Diversion Agreements is not case specific and thus cannot be deemed to recite sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt.” Id.

Iqbal was not binding on the Board in the instant case. However, the Board saw fit to distinguish the instant case from Iqbal. The Board stated that the respondent’s admission of guilt in the stipulation of evidence was “tethered to the facts and offense elements charged in the indictment…” Note that this is different from the situation described in Iqbal where the court determined that the language of New York’s Pretrial Diversion Agreements are not case specific but general, meaning that the incorporated admissions of guilt were not tethered to specific evidence relating to the elements charged in individual indictments. The Board also added that the respondent’s stipulation of evidence included a waiver of any opposition to its admission if his pretrial intervention agreement were to be voided.

It is noteworthy that the Board saw fit to distinguish the instant case from Iqbal, which was both a trial court rather than appellate court decision and non-binding in the instant case. This suggests that the Board may see Iqbal as describing a situation in which a pretrial intervention agreement would not fall under section 101(a)(48)(A). Please see our full article to learn more about the Iqbal decision [see article].

Conclusion

Matter of Mohamed makes clear that whether entry into a pretrial intervention agreement qualifies as a conviction depends on whether it meets the definition of a conviction in the immigration laws and not whether it constitutes a conviction under state law. It is therefore important for individuals to understand that the language of the INA is decisive in determining whether something is a “conviction” for immigration purposes. Matter of Mohamed describes the types of conditions that would render a pretrial intervention agreement, or similar agreement, a “conviction” under the INA. Whether such an agreement would be an immigration “conviction” in other cases or jurisdictions will depend on the specific facts. An alien facing criminal charges of any sort should always seek expert immigration advice regarding the effect that different case outcomes may have on his or her immigration situation.