- Introduction: Matter of Cervantes Nunez, 27 I&N Dec. 238 (BIA 2018)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 238-39

- Arguments on Appeal: 27 I&N Dec. at 239-40

- Relevant Statutes

- Use of the Categorical Approach: 27 I&N Dec. at 240-241

- Relevant Points Regarding 18 U.S.C. 16: 27 I&N Dec. at 240, 241 n.3-4

- Immigration Judge Decision: 27 I&N Dec. at 241

- Board Determines that Conviction is for a Crime of Violence: 27 I&N Dec. at 241-44

- Interesting Footnote: 27 I&N Dec. at 242 n.5

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Cervantes Nunez, 27 I&N Dec. 238 (BIA 2018)

On March 15, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published decision in Matter of Cervantes Nunez, 27 I&N Dec. 238 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. The question before the Board was whether the crime of attempted voluntary manslaughter in violation of sections 192(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code was an aggravated felony crime of violence under section 101(a)(43)(F) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The Board concluded that the California statute, which required that a defendant act with specific intent to cause the death of another person, defines an aggravated felony crime of violence “notwithstanding that the completed offense of voluntary manslaughter itself is not such an aggravated felony.”

As we will see in the article, the Board’s decision hinged on the fact that the statute for voluntary manslaughter was categorically over-broad with regard to the definition of “crime of violence” because it encompassed reckless acts, whereas attempted voluntary manslaughter under California law only encompassed acts committed with the “specific intent to kill.”

In this article, we will examine the facts and procedural history of Matter of Cervantes Nunez, the Board’s reasoning and conclusions, and what the new precedent means going forward.

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 238-39

The respondent, a native and citizen of Mexico, was admitted to the United States as a lawful permanent resident in 1965.

On March 15, 1991, the respondent was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in violation of section 192(a) of the California Penal Code and of attempted voluntary manslaughter in violation of sections 192(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code. He was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 1 year and 8 months. This sentence included a 1-year enhancement under section 12022.7 of the California Penal Code for inflicting great bodily injury in the commission of a crime.

As a result of the convictions, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) filed a notice to appear alleging that the respondent was removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the INA for having been convicted of an aggravated felony. Specifically, the DHS charged that the respondent’s conviction in violation of section 192(a) for voluntary manslaughter was an aggravated felony crime of violence under section 101(a)(43)(F).

The DHS subsequently conceded that the respondent’s conviction for voluntary manslaughter under section 192(a) was not an aggravated felony crime of violence. However, the DHS lodged an additional charge that the respondent’s conviction for attempted voluntary manslaughter in violations of sections 192(a) and 664 was for an aggravated felony crime of violence under INA section 101(a)(43)(F) and an attempt to commit an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(U).

In removal proceedings, the Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent was not removable as charged for the voluntary manslaughter conviction because section 192(a) of the California Penal Code was indivisible and categorically overbroad relative to the definition of a crime of violence in section 101(a)(43)(F) of the INA. Furthermore, the Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent’s conviction for attempted voluntary manslaughter under sections 192(a)( and 664 of the California Penal Code was neither an aggravated felony crime of violence under section 101(a)(43)(F) of the INA nor an attempt to commit an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(U). As a result of these conclusions, the Immigration Judge terminated removal proceedings against the respondent. The DHS appealed from the Immigration Judge’s decision to the BIA.

Arguments on Appeal: 27 I&N Dec. at 239-40

On appeal, the DHS argued that the respondent’s conviction for attempted voluntary manslaughter under sections 192(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code was an aggravated felony crime of violence, notwithstanding t that the completed offense of voluntary manslaughter under section 192(a) was not an aggravated felony crime of violence. In response, the respondent argued that attempted voluntary manslaughter under sections 192(a) and 664 was not an aggravated felony crime of violence under the categorical approach. Additionally, the respondent argued that his sentence for attempted voluntary manslaughter did not satisfy the 1-year term of imprisonment requirement in section 101(a)(43)(F) of the INA.

Relevant Statutes

Before continuing, we must examine the relevant statutes at issue in Matter of Cervantes Nunez.

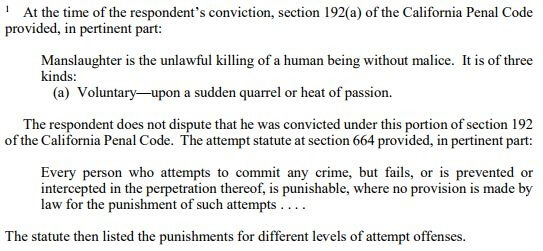

First, the Board excerpted the pertinent parts of sections 192(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code at the time of the respondent’s conviction at 27 I&N Dec. at 239 n.1:

As we explained, the DHS did not contest on appeal that the completed offense of voluntary manslaughter under section 192(a) was not an aggravated felony crime of violence. Accordingly, the contested question before the Board was whether the offense of attempted voluntary manslaughter under sections 192(a) and 664 was an aggravated felony crime of violence.

The provision for aggravated felony crime of violence is found in section 101(a)(43)(F) of the INA. The statute defines an aggravated felony crime of violence as an offense (1) defined in 18 U.S.C. 16 and (2) for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year. The DHS specifically alleged that the respondent’s attempted voluntary manslaughter conviction was a “crime of violence” under 18 U.S.C. 16(a), which covers “an offense that has an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another…”

Although the DHS charged that the respondent’s conviction was also an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(U), which covers attempts to commit any aggravated felony listed under section 101(a)(43), the Board did not find it necessary to determine whether the respondent’s conviction was covered by section 101(a)(43)(U) because it ultimately determined that the conviction was covered by section 101(a)(43)(F). 27 I&N Dec. at 244 n.6. Accordingly, the Board provided no analysis of the section 101(a)(43)(U) charge.

Use of the Categorical Approach: 27 I&N Dec. at 240-241

In order to determine whether the respondent’s conviction was for an aggravated felony crime of violence, the Board employed what is called the categorical approach. Citing to Mathis v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2243, 2248 (2016) [PDF version] [see article], the Board explained that the categorical approach focuses on the “elements” of the crime rather than the underlying facts of the case. An element is something that must be proven in order to sustain a conviction.

The question in the instant case thus was whether all of the elements of sections 192(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code were encompassed by the Federal generic definition of a crime of violence found in section 101(a)(43)(F) of the INA. If so, then the California conviction would be for an aggravated felony crime of violence. To this effect, the Board quoted from its decision in Matter of Delgado, 27 I&N 100, 101 (BIA 2017) [PDF version] [see article]: “[I]f ‘the elements of the state crime are the same as or narrower than the elements of the federal offense, then the state crime is a categorical match and every conviction under that statute qualifies as an aggravated felony.’” (Emphasis added by Board. Internal citation omitted.) However, if the conduct covered by the California statutes was broader than the Federal generic definition of a crime of violence, the California statutes would be categorically overbroad and not categorically define a crime of violence.

Courts may look to State law to determine whether a statute defines alternative elements (things required to sustain a conviction) or means (ways of violating the statute). A statute that sets forth alternative elements may be divisible, in which case an adjudicator may look to the record of conviction to determine under which part of the statute the respondent was convicted. However, a statute that merely sets forth alternative means of committing crime is not divisible. Please see our series of articles on divisibility in the criminal aliens contest to read more about this subject [see index].

Relevant Points Regarding 18 U.S.C. 16: 27 I&N Dec. at 240, 241 n.3-4

In Leocal v. Ashcroft, 543 U.S. 1, 9 (2004) [PDF version] [see article], the Supreme Court held that the term “use” in 18 U.S.C. 16(a) “requires active employment” of force and denotes volition, or the conscious intent to use force. The Board noted this in Matter of Kim, 26 I&N Dec. 912, 914 (BIA 2017) [PDF version] [see article]. In Johnson v. United States, 559 U.S. 133, 140 (2010) [PDF version], the Supreme Court held that the phrase “physical force” means “violent force-that is, force capable of causing physical pain or injury to another person.”

The instant case arose in the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, making applicable precedents of the Ninth Circuit controlling for the Board. Under the case law of the Ninth Circuit in Fernandez-Ruiz v. Gonzales, 466 F.3d 1121, 1130 (9th Cir. 2006) (en banc) [PDF version], element of “recklessness” is not a sufficient mens rea (mental state) for establishing that a conviction is a crime of violence under 18 U.S.C. 16. In Voisine v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2272, 2280 n.4 (2016) [PDF version] [see article], the Supreme Court left open the question of whether “recklessness” was a sufficient mental state for a conviction to fall under 18 U.S.C. 16. Interestingly, the Board in the instant case noted that the Ninth Circuit in United States v. Benally, 843 F.3d 350, 354 (9th Cir. 2016) [PDF version] suggested that Voisine may suggest that reckless conduct can constitute a crime of violence. Nevertheless, Fernandez-Ruiz remains controlling in all cases arising in the Ninth Circuit. Please see our supplemental article on the possible effects of Voisine in the immigration context [see article].

Immigration Judge Decision: 27 I&N Dec. at 241

As we noted, the Immigration Judge held that attempted voluntary manslaughter under sections 192(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code did not categorically define a crime of violence under 18 U.S.C. 16(a). The Immigration Judge’s reasoning was grounded in the fact that a violation of section 192(a) — a completed voluntary manslaughter offense — does not in and of itself require volitional use of force, as required by Leocal. To this effect, the Immigration Judge relied on controlling Ninth Circuit precedent from Quijada-Aguilar v. Lynch, 799 F.3d 1303, 1306-07 (9th Cir. 2015) [PDF version], wherein the Ninth Circuit held that a conviction for voluntary manslaughter under section 192(a) is not categorically a crime of violence under 18 U.S.C. 16(a) because it encompasses merely reckless conduct. The Immigration Judge relied on jury instructions for section 192(a) to determine that the statute was not divisible.

Board Determines that Conviction is for a Crime of Violence: 27 I&N Dec. at 241-44

The Board agreed with the Immigration Judge that voluntary manslaughter under section 192(a) of the California Penal Code is not categorically a crime of violence because it encompasses both intentional and reckless conduct. However, the Board would, for the following reasons, conclude that attempted voluntary manslaughter under sections 192(a) and 664 is categorically a crime of violence and is not over-broad relative to 18 U.S.C. 16(a).

In People v. Gutierrez, 5 Cal. Rptr. 3d 256, 260-61 (Cal. Ct. App. 2003) [PDF version], the California Court of Appeals stated that “attempted voluntary manslaughter cannot be premised on the theory [that a] defendant acted with conscious disregard for life, because it would be based on the ‘internally contradictory premise’ that one can intend to commit a reckless killing.” The California Court of Appeals is not the only court to reach this conclusion. The Board noted that in United States v. Moreno, 821 F.3d 223, 230 (2d Cir. 2016) [PDF version], the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that “it is legally impossible to attempt to commit [a] reckless” act. The Third Circuit held similarly in Knapik v. Ashcroft, 384 F.3d 84, 91 (3d Cir. 2004) [PDF version].

However, the Board cited to several California Court of Appeals decisions making clear that proof of the commission of attempted voluntary manslaughter entails evidence of a more culpable mental state than mere recklessness. In the first of the numerous examples, the Board noted that in People v. Speight, 174 Cal. Rptr. 3d 454, 466 (Cal. Ct. App. 2014) [PDF version], the court held that an individual must act with “the specific intent to kill another person” to be convicted for attempted voluntary manslaughter.

For the foregoing reasons, the Board concluded that attempted voluntary manslaughter under California law — unlike voluntary manslaughter — “necessarily involves the volitional ‘use’ of force contemplated by Leocal.”

Next, the Board concluded that, under controlling Ninth Circuit precedent, attempted voluntary manslaughter also necessarily involves the use of “violent force,” which is required under Johnson. Here, the Board cited to Arellano Hernandez v. Lynch, 831 F.3d 1127, 1130-31 (9th Cir. 2016) [PDF version], cert. denied, 137 S.Ct 2180 (2017). In Arellano Hernandez, the Ninth Circuit held that the offense of attempted criminal threats under sections 422(a) and 664 of the California Penal Code was a categorical crime of violence under 18 U.S.C. 16(a). The Court noted that section 422 required a violator to “willfully threaten[] to commit a crime which will result in death or great bodily injury to another person…” Accordingly, it held that the elements of attempted criminal threats “necessarily include a threatened use of physical force ‘capable of causing physical pain or injury to another person.”

The Board explained that, in order to convict an individual for attempted violated manslaughter, a jury must find that the individual have acted with “a specific intent to cause the death of another person…” Accordingly, “all violations of these provisions must involve the intent to commit an act of force capable of resulting in death.” The Board quoted from the decision of the United States District Court for the District of Utah in United States v. Checora, 155 F.Supp. 3d 1192, 1197 (D. Utah 2015) [PDF version], wherein the Court stated that “[i]t is hard to imagine conduct that can cause another to die that does not involve physical force against the body of the person killed.”

Accordingly, while noting that it is perhaps “counterintuitive” that a conviction for voluntary manslaughter in California was not categorically an aggravated felony while a conviction for attempted voluntary manslaughter was categorically an aggravated felony, the Board reached this holding. It explained that “[u]nlike the completed crime of voluntary manslaughter under California law, which encompasses reckless conduct … attempted voluntary manslaughter requires the specific intent to kill.” The Board noted that, while the statutes for voluntary manslaughter did not explicitly require the “specific intent to kill,” it was evident under Ninth Circuit precedents that the statute “inherently presupposes the use of ‘physical force.’”

The Board then rejected the respondent’s argument that his sentence enhancement of one year under section 12022.7 of the California Penal Code for inflicting great bodily injury in the commission of a crime did not satisfy the “term of imprisonment [of] at least one year” requirement of section 101(a)(43)(F). Here, the Board stated that the respondent “[did] not offer any specific arguments or cite any legal authority for this assertion, which we do not find persuasive.”

For these reasons, the Board sustained the DHS’s appeal, reinstated removal proceedings, and remanded the record to the Immigration Judge to give the respondent an opportunity to apply for any forms of relief for which he may be eligible.

Interesting Footnote: 27 I&N Dec. at 242 n.5

The instant case did not involve a plea agreement. However, in a footnote, the Board found it worth noting that “unlike some other states, California does not permit convictions by plea to legally impossible crimes, such as attempted recklessness.” To this effect, the Board noted that New York has permitted please to legally impossible crimes in certain cases. Although the Board did not elaborate further on this point, it may be worth bearing in mind if a case with similar facts to Matter of Cervantes Nunez arises in a state that sometimes permits pleas to legally impossible crimes.

Conclusion

By the Board’s own admission, the result it reached in Matter of Cervantes Nunez may seem counter-intuitive. However, it stemmed from the application of the categorical approach, which requires adjudicators to look solely to the language of the statute of conviction. While all parties ultimately agreed that voluntary manslaughter under California law was categorically over-broad, the Board accepted the DHS’s argument that attempted voluntary manslaughter under California law encompassed only actions with “the specific intent to kill,” making it narrower than the provision for completed voluntary manslaughter.

The main significance of the decision is the Board’s conclusion that attempt offenses, by their nature, entail the requirement of proof of intent to engage in the violent or otherwise criminal conduct entailed in the commission of the underlying crime notwithstanding that the underlying crime may involve merely reckless conduct. Whether Matter of Cervantes Nunez applies in a specific case will depend on the language of the specific statutes involved. An individual facing criminal charges or removal based on a conviction should consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance.