Introduction

On June 1, 2017, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a 146-page report titled “Immigration Courts: Actions Needed to Reduce Case Backlog and Address Long-Standing Management and Operations Challenges.” The report focuses on backlogs in the processing of immigration cases at the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR), and it details the dramatic increase in processing times at the EOIR over the past decade. The report makes 11 recommendations for beginning to address the issues. In this article, we will examine key points from the GAO report as well as its recommendations for the EOIR. In so doing, we will rely on the following two documents that we have uploaded for those who want to follow along:

One-Page Report Highlights [PDF version];

Full Report [PDF version]; and

GAO Recommendations [PDF version].

Page 21-22 of Full Report: Growing Backlogs (FY 2006-2015)

On Page 21 of the full report, the GAO provides statistics on the annual caseloads for immigration courts from FY 2006 to FY 2015.

First, the GAO found that new case receipts at immigration courts have remained relatively steady over the sampled years. Interestingly, the number of new case receipts has been gradually declining since 2009. From FY 2006-2009, the new case receipts ranged from about 247,000 to 256,000 annually. However, in FY 2015, there were only about 202,000 new cases.

There has been a slow but gradual increase in other case receipts (e.g., motions to reopen, motions to reconsider, and motions to recalendar). There were about 50,000 such receipts in FY 2006 and about 108,000 in FY 2015.

However, in this period from FY 2006 to FY 2015, the case backlog has increased dramatically. The GAO found that the total case backlog was about 212,000 in FY 2006, and it dipped slightly under that at its lowest point in the sample in FY 2009. However, since 2009, the case backlog has increased each year. At the beginning of FY 2015, the case backlog stood at a staggering 437,000 cases, more than double the backlogs in FY 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009. This has led to a marked increase in case processing times. In FY 2006, the median processing time for backlogged cases was 198 days. In FY 2015, that had risen to 404 days.

The GAO explained that due to the backlogs, “some immigration courts were scheduling hearings several years in the future…” Half of all courts, as of February 2, 2017, had individual merits hearings “scheduled as far as June 2018 or beyond.” However, this varied from court to court. The GAP noted that while one immigration court “had individual hearings scheduled out no further than March 2017,” another unidentified hearing court had hearings scheduled as far out as February 2022.

Interestingly, on page 23 of the report, the GAO noted that although the number of immigration judges had increased from 212 in FY 2006 to 247 in FY 2015, the annual number of completed cases had declined from just under 300,000 to just over 200,000 from FY 2006 to 2015.

Page 26: Increase in Median Number of Days for Initial Case Completion Time

In FY 2006, the median number of days for initial case completion (all case types) was 43. This hit a low point in the sample for FY 2008 and 2009, when it stood at 28 and 29 days, respectively. However, beginning in FY 2013, the overall number of days for initial case completion rose sharply. FY 2013 saw the highest number at 301 days, and in FY 2015 it remained a very high 286 days.

Interestingly, the increase has not been uniform by case type. For example, the median wait time for asylum only proceedings has been over a year for all but three years in the sample. Withholding only median wait times for initial decisions has also remained relatively steady over the sampled years.

The most substantial increase in median wait times has been in regular removal proceedings, which track very closely with the number for all cases. Similarly to the average time for all case times, the median days required for regular removal proceeding cases was no more than 65 for any year through FY 2011. Then, from FY 2012 to FY 2015, the numbers were 140, 321, 316, and 336, respectively. There was also a substantial increase in other case types.

The GAO explained that the EOIR offered numerous factors that may have contributed to the increase in median wait times. One reason it noted was the surge of cases arising from migrants crossing the Southwest Border beginning in FY 2014. Specifically, the EOIR noted that cases involving unaccompanied alien children often take longer to adjudicate than other case types.

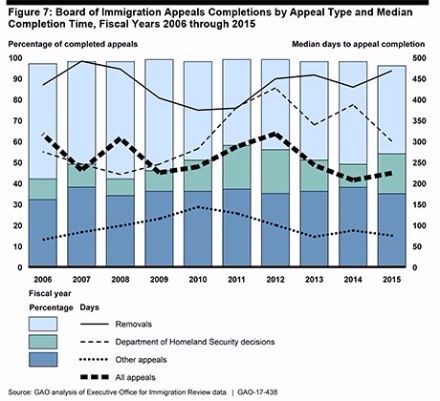

Page 31-33: BIA Appeal Wait Times Decrease

The GAO found that the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) wait times actually decreased on average because BIA appeal receipts declined at a faster rate than appeal completions. The overall median time it took for the BIA to complete any type of appeal was 317 days in FY 2006. In FY 2015, it was only 224 days. The following is a chart of BIA appeals completions by appeal time and median completion time on an annual bases:

Page 76: Average Case Completions Per Judge

In FY 2015, there were 584 case completions per immigration judge.

Page 87-98: Recommendations and Responses

In light of the increasing backlogs in immigration courts, the GAO made 11 recommendations to the EOIR (see introduction for PDF).

The first two recommendations had to do with implementing new methods for properly hiring staff at the EOIR and creating a new hiring strategy for immigration judges. The third and fourth recommendations dealt with creating oversight to help the EOIR meet cost and schedule expectations. In points five through eight, the GAO recommended that the EOIR collect complete and reliable data on the EOIR’s use of video teleconference for immigration hearings to ensure that these proceedings are outcome-neutral, meet all user needs, and function properly. In point nine, the GAO recommends that the EOIR establish and monitor comprehensive case completion goals, “including a goal for completing non-detained cases not currently captured by performance measures…” Point ten calls for the EOIR to systematically analyze immigration court continuance data in order to address operational challenges and related areas for further guidance and training. Finally, the GAO recommended that the EOIR update its policies and procedures “to ensure the timely and accurate reporting of notices to appear.”

The GAO explained that the EOIR had stated that it agreed with most of the 11 recommendations and that it had begun to address them. However, GAO took the position that the steps taken thus far by EOIR do not fully address the recommendations. Furthermore, the EOIR did not state whether it agrees with individual recommendations. EOIR provided comments on recommendations 1-5. Regarding the first three recommendations, GAO believed that the EOIR was taking steps to address them but still had work to do in all three areas. Regarding video teleconference hearings, the EOIR noted that five U.S. Courts of Appeals have upheld the use of video teleconferencing in proceedings, but that it was nevertheless open to collecting more data. However, the EOIR did not agree with the recommendation that it solicit feedback from respondents in video teleconference hearings. The EOIR agreed in full with recommendations that it should establish and monitor comprehensive case completion goals, analyze continuance data, and update guidance recording notices to appear.

It is worth noting that the EOIR disagreed with the GAO’s methodology at certain points. Most of these regard aspects of the report not discussed in this article. However, there is one point we addressed in detail. The EOIR took the position that “the report is missing a contextualized discussion of why its caseload has grown.” The GAO disagreed, noting that it listed several factors that contributed to the increase (e.g., the number of cases involving unaccompanied alien children).

Analysis and Conclusion

The increasing backlog in the immigration courts is a serious problem for our immigration system. This is especially true with regard to the dramatically increasing wait times for adjudication of regular removal cases. The problems faced by the immigration courts are complicated, and there is no single solution to gradually decreasing the wait times. The GAO report is a valuable contribution to the discussion, and even if the EOIR disagrees with some of its methodology and solutions, there is still much to be gleaned from carefully studying its findings and recommendations. Furthermore, the Department of Justice (DOJ) is working to hire new immigration judges expeditiously in accordance with President Donald Trump’s January 25, 2017 Executive Orders.

Because the GAO report is 146 pages, we were only able to cover it in brief on site. We focused on information that may be of interest to stakeholders and laymen alike. Stakeholders and other interested persons should read the report in more detail to see the GAO’s full analysis, including on many points that we did not discuss. The appendices beginning on page 99 are especially interesting in that they include the detailed statistics relied upon by the GAO in forming its recommendations.