- Introduction: Special Immigrant Juveniles

- Background of Special Immigrant Juvenile Classification

- Eligibility Requirements for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status

- Conclusion

Introduction: Special Immigrant Juveniles

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) contains provisions providing for special protections for “special immigrant juveniles.” In general, an unmarried child under the age of 21 may be eligible for special immigrant juvenile classification if he or she has been subject to state juvenile court proceedings related to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or something similar under state law. Furthermore, the juvenile court must have determined that the child cannot be reunified with his or her parents due to abuse, neglect, or abandonment and that the child’s best interests would not be served were he or she to be returned to his or her home country. An alien minor who is granted special immigrant juvenile classification may then seek adjustment of status as an employment-based fourth preference special immigrant.

In this article, we will provide a general overview of the eligibility requirements for special immigrant juvenile classification with reference to the applicable statutes, regulations, judicial and administrative precedents, and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Policy Manual (PM). We discuss the required evidence and petitioning process [see article] and adjustment of status for special immigrant juveniles in a separate article [see article] in separate posts.

To learn more about special immigrant juvenile classification, please see our growing selection of articles on site [see category].

Background of Special Immigrant Juvenile Classification

The USCIS-PM describes in detail the purpose and background of special immigrant juvenile classification at 6 USCIS-PM J.1 [PDF version].

Congress created special immigrant juvenile classification as part of The Immigration Act of 1990, Pub. L. 101-649 (Nov. 29, 1990). Subsequently, provisions of the statutes relating to special immigrant juvenile status have been modified on five separate occasions, most recently as part of The Trafficking Victims Protection and Reauthorization Act (TVPRA 2008), Pub. L. 110-457 (Dec. 23, 2008).

The USCIS-PM explains that the special immigrant juvenile category was initially created “to provide humanitarian protection for abused, neglected, or abandoned child immigrants eligible for long-term foster care.” In subsequent revisions to the law, Congress added to the classes of children who are eligible for special immigrant juvenile protection. Under the current laws, the child immigrant need not be eligible for long-term foster care. Instead, a child whom a juvenile court determines cannot be reunified with one or both parents because of abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under state law is eligible for special immigrant juvenile protection, provided that the state court determines that it is not in the best interest of the child to be returned to his or her country of nationality or last habitual residence.

Eligibility Requirements for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status

The USCIS-PM discusses the eligibility requirements for special immigrant juvenile classification at 6 USCIS-PM J.2 [PDF version].

Special immigrant juvenile classification and the general eligibility requirements are set forth at section 101(a)(27)(J) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The more detailed eligibility requirements are found in the implementing regulations for section 101(a)(27)(J) at 8 C.F.R. 204.11. However, it is important to note that parts of the regulations at 8 C.F.R. 204.11 have been superseded by changes in statute, which was recognized at 6 USCIS-PM J.1(C) & n.9.

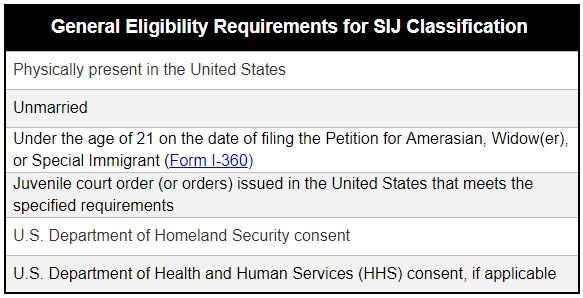

6 USCIS-PM J.2(B) explains that the alien must satisfy the following general requirements in order to be eligible for special immigrant juvenile classification:

Physical Presence Requirement

The first requirement is self-exclamatory. Special immigrant juvenile classification is not available to aliens abroad. Therefore, an alien must be physically present in the United States in order to apply for and be granted special immigrant juvenile classification.

Unmarried and Under the Age of 21 Requirement

The second and third requirements incorporate the INA’s definition of a “child” at section 101(b)(1) of the INA, which defines a “child” as an unmarried person under the age of 21. Thus, an alien who is married does not meet the definition of a “child” for special immigrant juvenile purposes regardless of his or her age. The USCIS-PM explains that this is the USCIS’s interpretation of the term “child” as it appears in section 235(d)(6) of the TVPRA 2008.

The TVPRA amended the special immigrant juvenile statutes to provide “age out protection.” The USCIS will consider the age of the alien at the time he or she files the Form I-360. Thus, if an alien files the Form I-360 while he or she is under the age of 21, the USCIS is prohibited from denying the petition “solely because the petitioner is older than 21 years of age at the time of adjudication.” However, a petitioner who marries while the petition is pending would become ineligible for special immigrant juvenile status.

At 6 USCIS-PM J.2(D)(4), the USCIS highlights an interesting point about how state laws affect the maximum age at which a child can obtain a qualifying order for special immigrant juvenile classification. Here, the USCIS states that “a juvenile court may not be able to take jurisdiction and issue a dependency or custody order for a juvenile who is 18 years of age or older even though the juvenile may file his or her petition with USCIS until the age of 21.” Thus, a juvenile under the age of 21 is permitted to file for special immigrant juvenile classification with the USCIS under federal law. However, in order for the Form I-360 to be approved, the child must have certain juvenile court orders (see next section), which fall under the jurisdiction of state law. States are required to follow their own laws in issuing orders that may qualify a child for special immigrant juvenile classification, and nothing in the INA directs states on how to implement their own laws. Thus, it is possible that in some jurisdictions a child older than 18 but younger than 21 may be able to obtain a juvenile court order that would suffice for purposes of establishing eligibility for special immigrant juvenile classification, whereas in other jurisdictions he or she may not be able to obtain such an order. We discuss the issue of jurisdiction in the next section (see fourth point).

Juvenile Court Order(s)

An alien must have state or juvenile court order(s) issued by a court in the United States that contain certain findings in order to be eligible for special immigrant juvenile classification. Here, it is important to note, as the USCIS did at 6 USCIS-PM J.1(A) & n.1, that the INA does not allow juvenile or state courts to make determinations based on provisions of the INA or associated immigration laws. Instead, these courts must rely upon state law and procedure in issuing orders that the USCIS may then consider as evidence in support of a Form I-360 for special immigrant juvenile classification.

First, the relevant orders must either (1) declare the petitioner for special immigrant juvenile classification dependent on a juvenile court or (2) legally commit the petitioner to or place the petitioner under the custody of an agency, a department of state, or a person or entity appointed by the state or juvenile court. A qualifying court order may place the petitioner with one parent provided that “reunification with the other parent is found to not be viable due to that parent’s abuse, neglect, or abandonment of the petitioner.”

The USCIS explains that “[c]ourt-ordered dependency or custodial placements that are intended to be temporary generally do not qualify for the purpose of establishing eligibility for [special immigrant juvenile] classification.” A court-appointed custodian who is appointed to act as a temporary guardian or caretaker of a child in loco parentis (in the place of a parent) is not considered to be a custodian for purpose of establishing eligibility for special immigrant juvenile status under TVPRA 2008.

Second, the state or juvenile court orders “must find that reunification with one or both parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under the relevant state child welfare laws.” In the previous paragraph, we noted that temporary custodians generally do not qualify a petitioner for special immigrant juvenile classification. Here, the USCIS explains that the “[l]ack of a viable reunification generally means that the court intends its finding that the child cannot reunify with his or her parent (or parents) remains in effect until the child ages out of the juvenile court’s jurisdiction.” (Emphasis added.) However, while a child’s parent being temporarily unavailable does not qualify him or her for special immigrant juvenile protection, “actual termination of parental rights is not required.”

The court’s finding that parental reunification is not a viable option must be based on the petitioner’s “parents” as defined under state law. The USCIS makes clear that the term “parents” does not include “step-parents” unless the step-parent in question “is recognized as the petitioner’s legal parent under state law…” In most cases, if the juvenile court determines that the person(s) in question is or are the petitioner’s parent(s), the USCIS will generally accept this as sufficient for purpose of adjudicating a petition for special immigrant juvenile classification. However, the USCIS may request additional evidence notwithstanding the juvenile court order “if the record does not establish that the person (or persons) is the petitioner’s parent (or parents)…”

It is worth reiterating that, in the past, the INA required that the juvenile court deem the child eligible for long-term foster care after determining that the child could not viably be reunited with a parent due to certain specified grounds. Subsequent to TVPRA 2008, the USCIS no longer requires that the juvenile court deem the child eligible for long-term foster care, although such a determination may still support a juvenile’s eligibility for special immigrant juvenile classification.

Third, despite the fact that juvenile courts cannot make decisions about a child’s immigration status, including removal or deportation to another country, the USCIS requires that the juvenile court make a determination “that it would not be in the best interest of the petitioner to be returned to the country of nationality or last habitual residence of [him or her] or his or her parents” as a prerequisite for approval of Form I-360 petitions for special immigrant juvenile classification.

Procedures and standards for making best interests determinations vary among the states. A state court determination “that a particular custodial placement is the best alternative available to the petitioner in the United States” does not necessarily establish for the USCIS “that a placement in the petitioner’s country of nationality would not be in the child’s best interest.” 58 FR 42843-01, 42848 (Aug. 12, 1993).

In general, the USCIS will defer to the juvenile court’s best interest determinations. Nothing in the INA or USCIS policies requires juvenile courts “to conduct any analysis other than what is required under state law.”

Fourth, the order must be meet certain requirements in order to be “valid” for special immigrant juvenile purposes. The juvenile court must be required to follow the laws of the state on jurisdiction. Under 8 C.F.R. 204.11(a), the court that issues the order “must have jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the care and custody of juveniles.” (Quoted from 6 USCIS-PM J.2(D)(4).) Please see our section titled “Unmarried and Under the Age of 21” [see section] for more information about how this provision interacts with the age requirement for special immigrant juvenile classification

In general, a juvenile court must have continuing jurisdiction over the petitioner both at the time the petitioner files a petition for special immigrant juvenile classification and when the petition is adjudicated. However, there are limited exceptions to this rule.

If the juvenile court’s continuing jurisdiction is broken because the court vacates or terminates its findings that the petitioner is eligible for special immigrant juvenile classification, the petitioner becomes ineligible. The petitioner also becomes ineligible if the juvenile court reunites him or her with the parent whom the court had previously determined could not viably have custody of the child due to findings of abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under state law.

However, if the juvenile court’s jurisdiction over the petitioner is broken solely because the petitioner was adopted or placed in a permanent guardianship, the petitioner remains eligible for special immigrant juvenile classification. The petitioner also remains eligible if his or her Form I-360 petition is filed before he or she turns 21, but the juvenile court loses jurisdiction solely because the petitioner attained the age of 21 while the petition is pending.

An interesting scenario arises if a petitioner, during the pendency of a petition, moves out of the jurisdiction of the juvenile court that issued the relevant order. Generally, a juvenile court does not lose jurisdiction if the petitioner moves to a different jurisdiction. It maintains jurisdiction “when it orders the child placed in a different state or makes a custody determination and the legal custodian relocates to a new jurisdiction.” However, if the child relocates to a new jurisdiction and is no longer living in a court ordered placement with a court ordered custodian, he or she will have to submit new evidence to establish eligibility for special immigrant juvenile classification. This evidence may either be in the form of materials showing that the court still exercises jurisdiction over the petitioner or in the form of a new juvenile court order from the court that has jurisdiction. This is outlined at 8 C.F.R. 204.11(c)(5). The USCIS further explains that if an original order is vacated due to the child moving to a new jurisdiction, but a new order is issued in the child’s new jurisdiction, “USCIS considers the dependency or custody to have continued through the time of adjudication of the SIJ petition, even if there was a lapse between court orders.”

Fifth, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which encompasses the USCIS, must give consent in order for the juvenile court order to qualify a petitioner for special immigrant juvenile classification. Specifically, the USCIS must review the order to determine that it was bona fide. A bona fide order is one that “was sought to obtain relief from abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under state law, and not primarily or solely to obtain an immigration benefit.” This requirement is found in section 101(a)(27)(J)(iii) of the INA.

The PM explains that the USCIS relies on juvenile courts to make child welfare decisions. Accordingly, it “does not reweigh the evidence to determine if the child was subjected to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under state law.” However, the USCIS “requires that the juvenile court order or other supporting evidence contain or provide a reasonable factual basis for each of the findings necessary for classification as a SIJ.” The evidence need not be “overly detailed” to be “reasonable.” In most cases, the USCIS consents to a grant of special immigrant juvenile classification “when the order includes or is supplemented by a reasonable factual basis for all of the required findings.”

Although an order may not be sought “primarily or solely to obtain an immigration benefit,” the USCIS does “recognize[] that there may be some immigration motive for seeking the juvenile court order.” The USCIS notes that a petitioner may request an order “that compiles the findings of several orders into one order to establish eligibility for SIJ classification.” The USCIS states thatl orders in cases such as those are not necessarily not bona fide.

Health and Human Services Consent

If the child is in the custody of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and he or she seeks a juvenile court order that alters his or her custody or status placement, he or she must obtain consent from the HHS to the juvenile court’s jurisdiction. However, the USCIS explains that HHS consent is not required where the order “simply restates the petitioner’s current placement.”

Inadmissibility Does Not Apply

Inadmissibility grounds do not apply to special immigrant juvenile petitions. For this reason, a petitioner for special immigrant juvenile classification does not need to seek a waiver of inadmissibility if he or she is inadmissible.

Family Members Cannot Be Included

Family members of the petitioner for special immigrant juvenile classification cannot be included on the Form I-360. However, if the petition is approved and the special immigrant juvenile subsequently successfully adjusts to the status of lawful permanent resident, he or she may petition for qualifying family members through the family-sponsored immigration process.

It is important to note, however, that under section 101(a)(27)(J)(iii)(II) an alien who adjusts status based off a grant of special immigrant juvenile classification may not petition for his or her natural or adoptive parents, even if one of his or her parents was a non-abusive, custodial parent.

Conclusion

Special immigrant juvenile classification is a unique form of immigration protection for alien children who a court determines have been abused. The court must also determine that the child cannot be reunified with the abusive parent due to the abuse and that it is not in the child’s best interest to be placed back in his or her country of nationality (or his or her parents’ country of nationality). Individuals interested in obtaining case-specific guidance on any issue involving special immigrant juveniles should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately. In this article, we examined the general requirements for special immigrant juvenile classification. Please see our follow-up article on petitioning for special immigrant juvenile classification and related issues to learn more [see article].

To learn more about special immigrant juveniles generally, please see our growing selection of articles on the subject [see category].