Matter of Rosa, 27 I&N Dec. 228 (BIA 2018): Analyzing Whether State Conviction is Aggravated Felony Drug Trafficking

- Introduction: Matter of Rosa, 27 I&N Dec. 228

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 228-29

- Relevant Statutes and Arguments on Appeal: 27 I&N Dec. at 228-30

- Aggravated Felony Provision and Approach to Review: 27 I&N Dec. at 229-30

- Immigration Judge Decision and DHS Arguments: 27 I&N Dec. at 230-31

- Board Finds Cases IJ Relied Upon to be Distinguishable: 27 I&N Dec. at 231-32

- New Rule — May Look to Beyond Most Similar CSA Provision for Analogue: 27 I&N Dec. at 232

- Applying Rule to Instant Case: 27 I&N Dec. at 832-33

- Concurring Opinion: Board Member Blair T. O'Connor: 27 I&N Dec. at 234-37

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Rosa, 27 I&N Dec. 228

On March 14, 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) issued a published decision in Matter of Rosa, 27 I&N Dec. 228 (BIA 2018) [PDF version]. Under section 101(a)(43)(B) of the INA, an alien who engages in illicit trafficking of controlled substances as defined in Federal criminal law (including a drug trafficking crime) is considered to have committed an immigration aggravated felony. In Matter of Rosa, the Board held that when an adjudicator is deciding whether a State offense is punishable under the Federal Controlled Substances Act, which is determinative as to whether it is an immigration aggravated felony, the adjudicator “need not look solely to the provision of the Controlled Substances Act that is most similar to the State statute of conviction.” Following its new rule, the Board determined that a conviction in violation of section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes for possession with intent to distribute cocaine within 1,000 feet of school property is an aggravated felony drug trafficking crime.

In this article, we will examine the facts and procedural history of Matter of Rosa, the Board's decision, and what the decision means going forward. We will also examine an interesting concurring opinion by Board Member Blair T. O'Connor. To learn more about aggravated felony drug trafficking offenses in immigration law, please see our full article on the subject [see article].

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 228-29

The respondent, a native and citizen of the Dominican Republic, was a lawful permanent resident of the United States.

On February 20, 2004, the respondent was convicted of possession of cocaine with intent to distribute within 1,000 feet of school property in violation of section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes. Based on this conviction, the respondent was charged as removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the INA as an alien convicted of an aggravated felony drug trafficking crime under section 101(a)(43)(B). The Immigration Judge determined that the respondent was not removable based on the aggravated felony charge, but that he was removable under section 237(a)(2)(B)(i) as an alien convicted of an offense related to a controlled substance. However, the Immigration Judge granted the respondent's application for cancellation of removal under section 240A(a) of the INA, a benefit for which the respondent would have been ineligible had it been determined that he had been convicted of an aggravated felony.

Relevant Statutes and Arguments on Appeal: 27 I&N Dec. at 228-30

The question before the Board was whether the respondent's conviction in violation of section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes was an aggravated felony under the immigration laws. If the conviction was found to be an aggravated felony, than the respondent would not be eligible for cancellation of removal.

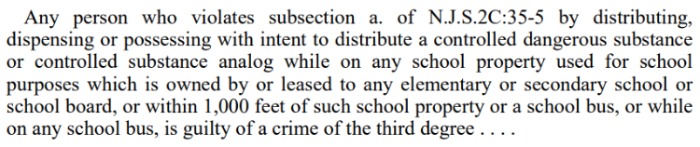

First, the following is the text of section 2C:35-7 at the time of the respondent's conviction, as excerpted by the Board at 27 I&N Dec. at 230:

The question before the Board was whether this statute categorically defined an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(B) of the INA, which defines as an aggravated felony the “illicit trafficking in a controlled substance (as defined in [21 U.S.C. 801]), including a drug trafficking crime (as defined in [18 U.S.C. 924(c)]).

In the forthcoming sections, we will examine the Board's analysis, conclusions, and other relevant cases and statutes that were cited to in the decision.

Aggravated Felony Provision and Approach to Review: 27 I&N Dec. at 229-30

In Evanson v. Att'y Gen. of U.S., 550 F.3d 284, 288 (3d Cir. 2008) [PDF version], the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit — under whose jurisdiction the instant case arose — held that a “drug trafficking crime,” as defined in section 101(a)(43)(B) of the INA, “means any felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. 801…).” Note, however, that the Controlled Substances Act is a federal law. Accordingly, the INA uses the language “publishable by” to encompass state convictions or other conduct that would fall under the umbrella of a Federal statute.

The Board stated that it would employ the “categorical approach” to determine whether the respondent's New Jersey conviction was punishable as a felony under the Controlled Substances Act. The Board explained that this approach would be “focusing on whether the elements of the respondent's State offense categorically define a felony under Federal law.” Citing to Moncrieffe v. Holder, 569 U.S. 184, 190 (2013) [PDF version]. In Matter of Delgado, 27 I&N Dec. 100, 101 (BIA 2017) [PDF version] [see article], the Board stated: “Under this categorical approach, if 'the elements of the state crime are the same as or narrower than the elements of the federal offense, then the state crime is a categorical match and every conviction under that statute qualifies as an aggravated felony.” An “element” is something that must be proven or admitted to in order to sustain a conviction under a statute. Where a statute contains “multiple alternative elements,” a court may look into the record of conviction to determine under which portion of the statute the individual was convicted . To learn about elements, please see our article on Mathis v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2243 (2016) [PDF version] [see article]. To learn about the categorical and modified categorical approaches more generally, please see our collection of articles on the issue [see index].

Immigration Judge Decision and DHS Arguments: 27 I&N Dec. at 230-31

The Immigration Judge determined that the respondent's conviction in violation o section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes (2004) [see section] was not an aggravated felony.

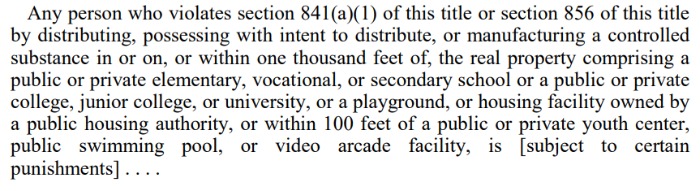

The Immigration Judge relied on an unpublished (non-precedent) decision of the Third Circuit in Chang-Cruz v. Att'y Gen. of U.S., 659 F.App'x 114, 116-119 (3d Cir. 2016) [PDF version]. In Chang-Cruz, the Third Circuit held that section 2C:35-7 does not categorically define an aggravated felony trafficking offense because (1) it was overbroad compared to 21 U.S.C. 860(a), and (2) it was indivisible (it found the statute to be unclear as to whether “distributing” and “dispensing” constituted alternative elements of the offense or alternative means of committing the offense). The Board excerpted the pertinent part of 21 U.S.C. 860(a), which we excerpt below:

Specifically, the Immigration Judge agreed with Chang-Cruz in finding that 21 U.S.C. 860(a) does not criminalize “dispensing,” unlike the New Jersey statute.

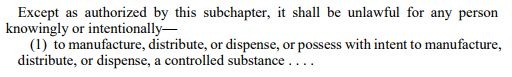

The DHS argued that the Immigration Judge's reliance on Chang-Cruz was improper. Namely, the DHS noted that Chang-Cruz was limited to assessing whether section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes would be punished as a felony under 21 U.S.C. 860, whereas section 2C:35-7 would be an aggravated felony if it was punishable under any provision of the Controlled Substances Act. The DHS argued that the respondent's conduct in the instant case would be punishable under 21 U.S.C. 841(a), which would also render it an aggravated felony. The Board excerpted 21 U.S.C. 841(a) as follows:

The Immigration Judge rejected the DHS's arguments, relying on the published Third Circuit decision in Wilson v. Ashcroft, 350 F.3d 377, 381 (3d Cir. 2003) [PDF version]. In Wilson, the Third Circuit found that 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) was “analogous” to a separate New Jersey state drug statute because it proscribed “identical conduct” to that statute.

Board Finds Cases IJ Relied Upon to be Distinguishable: 27 I&N Dec. at 231-32

The Board would conclude that both cases relied upon by the IJ were distinguishable from the instant case, and accordingly the Board agreed with the position of DHS.

First, the Board concluded that Wilson was distinguishable because “[t]he parties in that case did not argue that there were other appropriate Federal analogues to the State statute of conviction, as the DHS does here.” In short, the Board found nothing in Wilson precluded the conclusion that a separate statute than the one at issue in Wilson could be analogous to 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1).

Second, the Board also concluded that Chang-Cruz was distinguishable. In Chang-Cruz, the Government took the position that “21 U.S.C. 860 was the appropriate Federal analogue to section 2C:35-7.” Accordingly, the Third Circuit in Chang-Cruz did not reach the question faced by the Board in the instant case, namely, whether it may look to multiple provisions of the Controlled Substances Act collectively as an analogue in order to determine “if these provisions prohibit conduct identical to that proscribed by the State statute.”

New Rule — May Look to Beyond Most Similar CSA Provision for Analogue: 27 I&N Dec. at 232

The Board agreed with the DHS that adjudicators need not be restricted to looking at the Controlled Substances Act provision that is most similar to the State statute of conviction in determining whether there is an appropriate Federal analogue to the State statute. Instead, the Board concluded, agreeing with the DHS, that adjudicators may look to the Controlled Substances Act in its entirety for an appropriate analogue.

First, the DHS noted that Congress defined “drug trafficking crime” to encompass “any felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act” in 18 U.S.C. 924(c)(2). Second, the Board added that the aggravated felony provision in section 101(a)(43)(B) of the INA “contains definitions employed throughout the Controlled Substances Act…” Third, the Board noted that the Supreme Court of the United States decision in Lopez v. Gonzales, 549 U.S. 47, 60 (2006) [PDF version], does not limit the inquiry of adjudicators to the provision of the Controlled Substances Act that is most similar to the State statute of conviction.

Applying Rule to Instant Case: 27 I&N Dec. at 832-33

The Board concluded that 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) was an appropriate Federal analogue to section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes. Given this conclusion that 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) was an appropriate analogue, the Board held that the Immigration Judge's conclusion that 21 U.S.C. 860 was the only appropriate Federal analogue “was unreasonably limited.”

The Board noted that the Third Circuit held in United States v. Petersen, 622 F.3d 196, 204 (3d Cir. 2010) [PDF version], that 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) “is a lesser-included offense of [21 U.S.C. 860(a)].” In Petersen, the Third Circuit added: “In fact one of the statutory elements of [21 U.S.C. 860(a)] requires that [21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) have been violated.” These points formed the basis of the Board's conclusion that 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) is also an analogue to section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes.

The Board found that section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes was divisible as to the specific controlled substance underlying a conviction. This is because the Board concluded that the controlled substance involved was an element of the statute. For this reason, the Board found that the modified categorical approach was appropriate to determine which substance underlay the conviction.

The Board stated that “it is undisputed that the respondent's violation of section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes necessarily involved possession with intent to distribute cocaine.” The Board found that this offense was “clearly punishable as a felony under [21 U.S.C. 841].”

Regarding the element of the New Jersey statute of conviction requiring that the offense take place within a certain proximity to school property, the Board explained that this narrowed, rather than broadened, the scope of the State statute. See Matter of Delgado, 27 I&N Dec. at 101-02. This means that rather than making the New Jersey Statute overbroad with respect to 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1), it instead narrowed the scope of the State statute such that it covered a subset of conduct also covered by the Federal analogue. The Board summarized this point by stating that “the fact that the respondent possessed cocaine with the intent to distribute it within proximity to school property does not diminish the fact that he committed an aggravated felony drug trafficking crime in that location.” The Board added that holding that 21 U.S.C. 860 is the only appropriate Federal analogue to section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes “would lead to absurd or bizarre results,” something that the Supreme Court held should be avoided in Demarest v. Manspeaker, 498 U.S. 184, 191 (1991) [PDF version]. To this effect, the Board stated: “Clearly, it would be absurd to hold that possession of cocaine with the intent to dispense it is an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(B) of [the INA] but that the same crime committed within proximity to a school is not.”

Because the Board held that the respondent's State conviction satisfied all elements of 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1) and would be punishable as a felony under that Federal provision, the Board concluded that the respondent was removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the INA as an alien who had been convicted of an aggravated felony. Due to the aggravated felony conviction, the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal. For these reasons, the Board sustained the DHS's appeal, vacated the Immigration Judge's decision, and ordered the respondent removed to the Dominican Republic.

Concurring Opinion: Board Member Blair T. O'Connor: 27 I&N Dec. at 234-37

Board Member O'Connor wrote an opinion concurring with the Board's result in Matter of Rosa. Furthermore, he stated that he would have held that “all conduct punishable under section 2C:35-7 of the New Jersey Statutes is punishable as a felony under the Controlled Substances Act under either [21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1)] or [21 U.S.C. 860].” He wrote his separate concurring opinion “to note the absurdity of the legal manipulations we must go through to reach this common sense conclusion…”

Board Member O'Connor noted that “the conviction records in this case clearly establish that the respondent possessed cocaine with intent to distribute it within 1,000 feet of a school.” He stated that the conduct described in the conviction record was punishable under the Controlled Substances Act and, by effect, was an aggravated felony drug trafficking crime. He noted that Congress clearly intended for aliens convicted for such conduct to be removed and ineligible for relief from removal. However, Board Member O'Connor quoted from United States v. Davis, 875 F.3d 592, 595 (11th Cir. 2017) [PDF version], in stating that the categorical approach sent adjudicators “down the rabbit hole … to a realm where we must close our eyes as judges to what we know as men and women.”

Board Member O'Connor noted that the current approach for making criminal law determinations in immigration cases “has become increasingly complicated.” Here, he agreed with the majority that relying solely on 21 U.S.C. 860 in the instant case, as the Third Circuit did in Chang-Cruz, would lead to “absurd results.” However, quoting from Justice Samuel Alito's dissenting opinion in Mathis, 136 S.Ct 2268 (Alito, J., Dissenting), he took the position that the categorical approach and the rules on divisibility are “increasingly le[ading] to results that Congress could not have intended.” On this point, he echoed similar arguments made in a concurring opinion in Matter of Chairez, 27 I&N Dec. 21, 25-26 (BIA 2017) (Malphrus, concurring), which we cover on site [see article].

For these reasons, Board Member O'Connor stated that, while he agreed with the majority and the DHS that the Board should seek to avoid absurd results, he did not think that the new approach accomplished this goal, which he called “a sad commentary on the state of affairs when it comes to making criminal law determinations in immigration proceedings…” Although he agreed with the majority that the approach of appealing to different Federal analogues is “permissible,” he expressed concerns that the Board's decision will make the job of adjudicators dramatically more complicated. To this effect, he quoted from Justice Alito's dissent in Mathis, 136 S.Ct. at 2268 (Alito, J., dissenting): “I wish them good luck.”

Board Member O'Connor would have permitted adjudicators to look at multiple provisions of the Controlled Substances Act in combination to determine whether they cover a State statute in its entirety. He would have adopted this approach with respect to the broad “punishable by” language in section 101(a)(43)(B) of the INA, and as consistent with Lopez. In the instant case, this may have been dispositive had the Board determined that the respondent's statute of conviction was indivisible with respect to the underlying substance (Board Member O'Connor felt that the majority did not provide a substantive analysis of the statute on this question before finding that it was divisible). However, Board Member O'Connor stated his disagreement with restricting adjudicators to relying on the modified categorical approach in the case of a divisible overbroad statute, while noting that his position has been rejected repeatedly by the Supreme Court.

Conclusion

Matter of Rosa provides a broad reading to section 101(a)(43)(B) by allowing adjudicators to look at provisions of the Controlled Substances Act other than the provision that is most similar to the State statute of conviction. The Board's decision hinged on the broad language of section 101(a)(43)(B). The effect of this decision will generally depend on the language of the State statute of conviction in question.

Although the approach by Board Member O'Connor is not controlling, he raised interesting concerns regarding the increasing complexity of the criminal determinations in the immigration context. Like Board Member Malphrus in Matter of Chairez in 2017, Board Member O'Connor called upon Congress to implement a “congressional fix” to clarify the issues. This point will be worth watching going forward.

If an alien is facing removal charges, he or she should consult with an experienced immigration attorney immediately for case-specific guidance.