BIA Considers Whether Its Obstruction of Justice Rules Apply Retroactively (Matter of Cordero-Garcia)

- Introduction: Matter of Cordero-Garcia, 27 I&N Dec. 652 (BIA 2019)

- Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 652-53

- Analysis of 101(a)(43)(S): 27 I&N Dec. at 653-55

- Retroactivity Test Appropriate: 27 I&N Dec. at 655-57

- Applying the Retroactivity Test: 27 I&N Dec. at 658-63

- Conclusion

Introduction: Matter of Cordero-Garcia, 27 I&N Dec. 652 (BIA 2019)

On October 18, 2019, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) published a precedent decision in the Matter of Cordero-Garcia, 27 I&N Dec. 652 (BIA 2019) [PDF version]. On remand from the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, the Board held that the crime of dissuading a witness in violation of section 136.1(b)(1) of the California Penal Code is categorically an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). In so doing, the Board followed its recent precedent decision in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 27 I&N Dec. 449 (BIA 2018) [PDF version], which we have discussed on site in a separate article [see article]. The bulk of the Board's analysis dealt with whether its precedents could and should be applied retroactively.

In this article, we will examine the factual and procedural history of the Matter of Cordero-Garcia, the Board's analysis and conclusions, and what the decision will mean going forward.

Factual and Procedural History: 27 I&N Dec. at 652-53

On June 27, 2010, an Immigration Judge found the respondent in Matter of Cordero-Garcia removable under section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the INA as an alien convicted of an aggravated felony. Because that also meant the respondent was ineligible for cancellation of removal, the Immigration Judge ordered him removed. Specifically, the Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent's conviction for dissuading a witness in violation of section 136.1(b)(1) of the California Penal Code was an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the INA.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) subsequently filed a motion to reopen the removal proceedings for further consideration of whether the respondent's conviction was correctly an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43)(S). This DHS motion was prompted by the decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (in whose jurisdiction the instant case arose) in Trung Thanh Hoang v. Holder, 641 F.3d 1157 (9th Cir. 2011) [PDF version], which potentially weighed on whether the respondent's conviction fell under INA 101(a)(43)(S) under Ninth Circuit law (we discuss this in detail throughout the article). The Board denied the DHS's motion. On appeal before the Ninth Circuit, the Government moved to have Cordero-Garcia remanded to the Board. The Ninth Circuit remanded to the Board for further consideration of whether the crime of dissuading a witness in violation of section 136.1(b)(1) of the California Penal Code is an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under section 101(a)(43)(S) of the INA. In particular, the Ninth Circuit directed the Board to consider the issue in light of its intervening precedent decision in Valenzuela Gallardo v. Lynch, 818 F.3d 808 (9th Cir. 2016) [PDF version]. Subsequently, the Board published a precedent decision in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo II on remand from that Ninth Circuit decision. In the instant case, the Board would consider the applicability of the Valenzuela Gallardo decisions to the respondent's conviction in Matter of Cordero-Garcia and, specifically, whether Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) applied retroactively.

Analysis of 101(a)(43)(S): 27 I&N Dec. at 653-55

Section 101(a)(43)(S) of the INA defines “an offense relating to obstruction of justice, perjury or subornation of perjury, or bribery of a witness, for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year” as an aggravated felony. In considering whether an alien's criminal conviction falls under INA 101(a)(43)(S), the BIA applies the categorical approach. The categorical approach requires a comparison of the elements of the criminal conviction (that is, the things that must be proven to sustain the conviction) with the Federal generic definition of the 101(a)(43)(S) offense in question. In this case, the question was whether the elements of section 136.1(b)(1) constituted a categorical match with the Federal generic definition of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” under INA 101(a)(43)(S). We discuss the categorical approach further in our article on Mathis v. United States, 136 S.Ct. 2243 (2016) [see article].

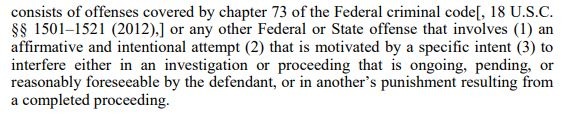

The Board initially provided its view of the generic Federal definition of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 25 I&N Dec. 838 (BIA 2012) [PDF version]. The Ninth Circuit did not defer to the Board's definition in this first Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision, finding it impermissibly vague. In response, the Board clarified its view of the generic definition of an offense relating to obstruction of justice in the second Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision at Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo, 27 I&N Dec. at 460 (BIA 2018), stating that an offense relating to obstruction of justice:

Based on its definition, the Board held in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo I and II that the crime of accessory to a felony under section 32 of the California Penal Code is an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice under INA 101(a)(43)(S). The Board explained that “[t]he California accessory statute required a violator to aid the principal, with knowledge that the principal has committed a crime, and with the specific intent to interfere in the principal's arrest, trial, conviction, or punishment.” Id. at 461. (Internal citations and quotations omitted.) We discuss the Board's analysis and conclusions in detail in our article on the Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo litigation [see article].

The question in the instant case was whether the respondent's conviction in violation of section 136.1(b)(1) of the California Penal Code was an aggravated felony offense relating to obstruction of justice. Citing to several California State court precedents, the Board explained that California law requires the State to prove the following in order to obtain a conviction under section 136.1(b)(1):

1. The defendant has attempted to prevent or dissuade a person

2. who is a victim or witness to a crime

3. from making a report to any peace officer or any designated officials.

(See Board's case citations at 27 I&N Dec. at 654)

From these California State court decisions, the Board gleaned that “section 136.1(b)(1) requires a specific intent to interfere in an investigation or proceeding.” The Board added that, “[w]here an individual attempts to prevent or dissuade a victim or witness from making a report of a crime to a peace officer or other designated official, an investigation or proceeding would necessarily be either ongoing, pending, or reasonably foreseeable.” Based on the prevailing construction of section 136.1(b)(1), the Board concluded that it categorically defined an aggravated felony relating to obstruction of justice, in accordance with the 2018 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision.

Retroactivity Test Appropriate: 27 I&N Dec. at 655-57

Having concluded that section 136.1(b)(1) of the California Penal Code categorically defines an aggravated felony under INA 101(a)(43)(S) under Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018), the Board would next consider whether Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) could be applied retroactively. The question was significant in the instant case because the respondent's conviction occurred before both the 2012 and 2018 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo precedent decisions.

The Board began by discussing the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in SEC v. Chenery Corp., 332 U.S. 194, 203 (1947) [PDF version], wherein the Supreme Court addressed in great detail retroactivity in the administrative law context. There, the Court explained that the mere fact that an administrative agency action may have retroactive effect does not, in and of itself, undermine the action's validity. However, “such retroactivity must be balanced against the mischief of producing a result which is contrary to a statutory design or to legal and equitable principles.” If the “mischief” of not giving action retroactive effect is greater than the ill effects of giving the action retroactive effect, then “it is not the type of retroactivity that is condemned by law.” The Court noted that “[e]very case of first impression has retroactive effect…”

The Board noted, however, that applying agency actions retroactively is disfavored. Velasquez-Garcia v. Holder, 760 F.3d 571, 579 (7th Cir. 2014) [PDF version]. In an opinion authored by now-Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit held that agency rules should be presumed to apply only prospectively unless Congress has clearly authorized retroactive application. De Niz Robles v. Lynch, 803 F.3d 1165, 1172 (10th Cir. 2015) [see article]. The Ninth Circuit, in whose jurisdiction the instant case arose, has also recognized a “presumption of prospectivity” in cases where it defers to a Board interpretation over its own prior interpretation of a statute. Betansos v. Barr, 928 F.3d 1133, 1143-46 (9th Cir. 2019) [PDF version].

Regarding the instant case, the Board noted that the Supreme Court has held that Congress unambiguously intended for the aggravated felony provisions of the INA to apply retroactively. INS v. St. Cyr, 533 U.S. 289, 318-19 & n.43 (2001) [PDF version]. Based on St. Cyr and Chenery, the Board concluded that it “may apply [its] decisions retroactively after proper consideration of the relevant factors…”

Controlling precedent from the Ninth Circuit provides that the retroactivity analysis is necessary when an administrative agency decision effects a change in law. Garfias-Rodriguez v. Holder, 702 F.3d 504, 518-19 (9th Cir. 2012) (en banc) [PDF version]. The Board considered whether its two Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decisions constituted a change in law. In the Ninth Circuit's remand of the first Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2012), it directed the Board to either consider a new construction of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” or to return to its prior construction articulated in Matter of Espinoza, 22 I&N Dec. 889 (BIA 1999) [PDF version], to which the Ninth Circuit had deferred in Trung Thanh Hoang v. Holder, 641 F.3d 1157 (9th Cir. 2011) [PDF version].

The Board took the position that not all precedents clarifying earlier decisions constitute a change in law, a view supported by Ninth Circuit precedent in Olivas-Motta v. Whitaker, 910 F.3d 1271, 1276 (9th Cir. 2018) [PDF version]. The Board concluded that its decision in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2012) did in fact depart from its first construction of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” in Matter of Espinoza. Furthermore, the Ninth Circuit had deferred to Matter of Espinoza before the Board published the first Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision . For this reason, the Board found that the retroactivity analysis was appropriate in the instant case.

Applying the Retroactivity Test: 27 I&N Dec. at 658-63

The Board applied the retroactivity test set forth in Montgomery Ward & Co. v. FTC, 691 F.2d 1322 (9th Cir. 1982) [PDF version],. because the instant case arose in the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit. The Board noted that the test is also used in the Second, Third, Fourth, Sixth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits [see article on circuit jurisdiction]. In light of this, the Board held as an additional matter that it would apply the Montgomery Ward test to retroactivity questions nationwide. The Board provided in a footnote, however, that “[t]o the extent that a court of appeals follows a different test … Immigration Judges and the Board should follow the law of that circuit.”

Quoting from Montgomery Ward (691 F.2d at 1333 (internal citation omitted)), the Board set forth the applicable test:

(1) whether the particular case is one of first impression,

(2) whether the new rule represents an abrupt departure from well established practice or merely attempts to fill a void in an unsettled area of law,

(3) the extent to which the party against whom the new rule applied relied on the former rule,

(4) the degree of the burden which a retroactive order imposes on a party, and

(5) the statutory interest in applying a new rule despite the reliance of a party on the old standard.

The Board concluded that the first factor was inapplicable in the instant case. While the Ninth Circuit held in Miguel-Miguel v. Gonzales, 500 F.3d 941, 951 (9th Cir. 2007) [PDF version], that the first factor is appropriately considered in the immigration context where the immigration agency has adopted a standard previously and then attempts to punish conformity to the prior standard under a new standard. The Board noted that the 2018 Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision came subsequent to decades of rulings by the BIA and the Ninth Circuit on the parameters of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” under INA 101(a)(43)(S) Thus, the issue was hardly a matter of first impression. The Ninth Circuit had previously held that questions about the unfairness in applying a new rule are best considered under the second and third factors. Garfias-Rodriguez v. Holder, 702 F.3d at 521. The Ninth Circuit explained its reasoning in that decision:

The second and third factors are closely intertwined. If a new rule 'represents an abrupt departure from well established practice,' a party's reliance on the prior rule is likely to be reasonable, whereas if the rule 'merely attempts to fill a void in an unsettled area of law,' reliance is less likely to be reasonable … [T]hese two factors will favor retroactivity if a party could have reasonably anticipated the change in the law such that the new 'requirement would not be a complete surprise.' Id.

Regarding section 101(a)(43)(S), the Board explained that the Ninth Circuit has acknowledged that Congress did not define “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” for purposes of the INA. Renteria-Morales v. Mukasey, 551 F.3d 1076, 1086 (9th Cir. 2008) [PDF version]. For more than two decades, the Board and Ninth Circuit have issued several decisions working out the parameters of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” under INA 101(a)(43)(S). The Ninth Circuit described these decisions as “an ongoing conversation or back-and-forth between this Court and the [Board] about the proper interpretation…” Betansos, 928 F.3d at 1144. The Board viewed this as “an important consideration in the retroactivity analysis.” For this reason, the Board summarized the pertinent BIA and Ninth Circuit precedents on the question:

Matter of Batista-Hernandez, 21 I&N Dec. 955, 961 (BIA 1997) [PDF version]: “[W]e concluded that the offense of accessory after the fact in violation of 18 U.S.C. 3 (Supp. V 1993) 'clearly relates to obstruction of justice,' notwithstanding the fact that the statute lacked an element of an ongoing investigation or proceeding.”

Matter of Espinoza: “[W]e held that misprision of a felony in violation of 18 U.S.C. 4 (1994) was not an offense relating to obstruction of justice.”

The Ninth Circuit deferred to the Board's generic definition of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” in Matter of Espionza in various decisions: See Trung Tranh Hoang, 641 F.3d at 1164; Renteria-Morales, 551 F.3d at 1086-87; Salazar-Luviano v. Mukasey, 551 F.3d 857, 861-63 (9th Cir. 2008) [PDF version]. The Board stated that the Ninth Circuit “drew” a definition from Matter of Espionza, however, “which, according to the court, required interference with an ongoing proceeding or investigation, although [Matter of Espinoza] did not itself articulate such a requirement and [Matter of Batistas-Hernandez] did not apply one.” One dissenting opinion in Trung Tranh Hoang made this same point and argued that the Ninth Circuit should have followed Matter of Batista-Hernandez. Trung Tranh Hoang, 641 F.3d at 1165-68 (Bybee, J., dissenting).

Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2012): The Board held that “the existence of [an ongoing criminal investigation or trial] is not an essential element of 'an offense relating to obstruction of justice.'”

Valenzuela Gallardo v. Holder, 818 F.3d at 811, 813-24 (9th Cir. 2015): The Ninth Circuit was concerned that the Board's construction of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2012) was unconstitutionally vague. Accordingly, it remanded to the Board in order for the Board to either articulate a new construction of the term or return to the Ninth Circuit's rendering of Matter of Espinoza.

Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018): The Board clarified Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2012), ultimately reaching the same result with respect to the ongoing investigation issue.

The Board concluded, based on the foregoing history, that the definition of the term “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” was unsettled. It added that under the construction previously adopted by the Ninth Circuit, there were many Federal obstruction statutes about which aliens, attorneys, and immigration judges could reasonably reach different conclusions on whether they fell under section 101(a)(43)(S).

The Board added that the Ninth Circuit has been mostly concerned with whether the Board's construction of 101(a)(43)(S) is entitled to administrative deference under Chevron, U.S.A, Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 842-43 (1984) [PDF version]. Having acknowledged that INA 101(a)(43)(S) is ambiguous, the question has been whether the Board's interpretation of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” is reasonable, the second part of the Chevron test. The circuits, however, do not all agree on whether the term “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” is, in fact, ambiguous. The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit concluded that the phrase “relating to obstruction of justice” is not ambiguous and further concluded that the Board's construction of the term in Matter of Espinoza was unnecessarily restrictive. Denis v. Att'y Gen. of U.S., 633 F.3d 201, 209 (3d Cir. 2011) [PDF version]. Thus, the Third Circuit never reached Chevron step two, instead adopting a broader construction of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” than did the Board in Matter of Espinoza on its own volition. The Board cited to the split between the Third and Ninth Circuits as further evidence of its conclusion that the proper construction of the phrase “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” remains unsettled.

The Board also concluded that its precedent decisions in Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo were not departures from well-established practice that litigants could have relied upon. The Board contrasted those decisions with its precedent in Matter of Diaz-Lizarraga, 26 I&N Dec. 847 (BIA 2016) [PDF version] [see article], wherein it revisited its standard for when a theft offense involves moral turpitude and revised its prior position that theft offenses only involve moral turpitude when they involve an intent to permanently deprive an owner of his or her property. Id. at 849. The United States Courts of Appeals for the Second, Fifth, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits have declined to give Matter of Diaz-Lizarraga retroactive effect finding found that it constituted a stark departure from well-established BIA precedent upon which litigants could have reasonably relied. (See 27 I&N Dec. at 661 for case list.) The Board found that there was no comparable departure in its two Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decisions.

The Board explained that there are myriad statutes containing elements that may relate to obstruction of justice. Accordingly, while it noted that its prior decisions regarding specific statutes, such as Matter of Espionza, may inform adjudicators with respect to different statutes, they are not dispositive. The Board explained that “[i]t was in this context” that it had rendered the two Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decision subsequent to its decision in Matter of Espionza. In contrast to the Ninth Circuit, the Board did not view Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2012) as a departure from Matter of Espinoza, but rather as a clarification of the decision in conjunction with a reaffirmation of Matter of Batista-Hernandez.

Thus, in accordance with the Montgomery Ward retroactivity test, the Board concluded that its decisions regarding “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” “were merely attempts to fill a void in an unsettled area of law and do not represent an abrupt departure from well-established practice.” The Board further concluded that it “cannot discern a settled 'former rule' on which the respondent may reasonably have relied under the third factor of the Montgomery Ward test.”

The Board assumed that application of the fourth factor in the Montgomery Ward test — the burden retroactive application of Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) would pose to the respondent — “strongly favor[ed]” the respondent due to the burden which removal from the United States would impose on him. Conversely, the Board assumed that the fifth factor — the statutory interest in applying the new rule — strongly favored the government's interest in applying the immigration laws uniformly.

After weighing the five Montgomery Ward retroactivity factors, the Board concluded that the holding of Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) is retroactive. The Board made clear, however, that this result of its retroactivity analysis regarding Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) was reflective of the specific facts and circumstances, and does not necessarily mean that a different Board precedent preceded by different facts must be given retroactive effect.

Based on its conclusion, the Board concluded that the respondent was removable and ineligible for cancellation of removal based on his conviction for an aggravated felony under INA 101(a)(43)(S), and dismissed his appeal.

Conclusion

There are two significant points to take away from Matter of Cordero-Garcia.

The most significant part of the decision is the Board's retroactivity analysis. Although the retroactivity analysis of any Board precedent will depend on the particular facts of the case, Matter of Cordero-Garcia provides a detailed example of how the Board will approach the issue. From this, we can glean whether the Board may be inclined to take the position that a precedent which, to one extent or another, differs from either its own prior interpretation of a provision or a Federal court's, should be applied retroactively.

The second significant part of its decision is the practical effect. The Board has taken the position that Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) should be applied retroactively, including in cases arising in the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit, where the INA 101(a)(43)(S) questions at issue were perhaps the most uncertain. Since the Ninth Circuit's earlier reading of Matter of Espinoza was narrower than the Board's construction of “an offense relating to obstruction of justice” in Matter of Batista-Hernandez and the Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo decisions, this is generally unfavorable to aliens charged with offenses that may plausibly be found to be offenses relating to obstruction of justice. It remains to be seen whether the Ninth Circuit will agree with the Board that Matter of Valenzuela Gallardo (2018) is not only entitled to deference, but also may be applied retroactively.

An alien facing removal charges should always consult with an experienced immigration attorney for case-specific guidance. Furthermore, aliens facing criminal charges or who are unsure about the possible immigration consequences of existing convictions should seek immigration counsel for guidance. We discuss related issues in our growing selections of articles on criminal aliens [see category] and removal and deportation defense [see category]. You may see our collection of articles on administrative precedent decisions under the INA in our article index [see index].